Trick or Treat? Ancient collection at Amgueddfa Cymru found to be modern

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the president of Amgueddfa Cymru, Lord Howard de Walden, formed a remarkable collection of ancient European arms and armour. The collection included a number of classical pieces - helmets, swords, spearheads, belts and armour that were mainly Greek and Roman - or so it was thought until work at Amgueddfa Cymru discovered otherwise...

The collection comes to Amgueddfa Cymru

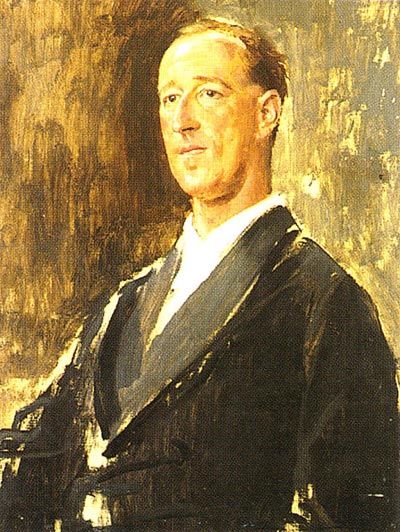

Portrait of Lord Howard de Walden (1880-1946)

Etruscan bronze 'helmet' embellished with gold showing half of the false patina removed

X-Ray of helmet

In 1945, Lord Howard offered to lend seventy-nine 'antique bronze objects' to the Museum. Following his death in 1946, his son donated the collection to the Museum.

In 1990 research by a Russian scholar had shown that some items from this collection had almost certainly been made in a jeweller's workshop in Odessa, south Russia between 1890 and 1910. Further investigation has revealed some of the objects to be totally genuine, but others reveal signs of being 'improved' or even manufactured more recently from antique metal parts fashioned into classical forms.

In order to meet the demand for classical antiques during this period, it was quite common to produce a particular object using ancient pieces from a number of sources, or in other words, a pastiche (a work of art that imitates the style of some previous work). There are also a number of fakes, where the metal used was wrong for the period of the object. Lord Howard de Walden was well aware of this, for when the loan to the Museum was being organised, he wrote 'there are certain pieces you may not wish to have, such as...several specimens of doubtful authenticity'.

Bronze 'helmet'

One such object that Museum conservators examined was a helmet, made of bronze and decorated with gold, apparently dating from the third century B.C.

The helmet was X-rayed to determine the condition of the metal and the extent of the corrosion, as well as to reveal its construction. However, the X-ray uncovered much more than was originally expected, for dense solder lines could be clearly seen criss-crossing the image. The helmet had undergone considerable restoration work in recent times; cracks had been filled with solder and holes patched with metal. To disguise these recent repairs a fake patina (the sheen on an object produced by age and use) mimicking corroded bronze had been applied over the top.

Analysis of the metal revealed that the bronze helmet was in fact old, and even the patches of metal used to repair the holes were ancient. However, there were indications that the gold was modern.

The investigations concluded that the helmet had been repaired and embellished with gold that would have increased its value and made it more desirable to collectors. This work may have been carried out at the turn of the twentieth century.

Should the modern repair work be removed or conserved?

In the end, it was decided to remove half the false patina in order to reveal the repair work below, for it was felt that the alterations were now part of the history of the object and could shed light on techniques employed at the time the helmet was collected.

Study of this important collection not only throws light on the ancient technology of the genuine pieces of classical arms and armour, but also the practices of the antiquities market a century ago.