Dreaming sometimes is not enough

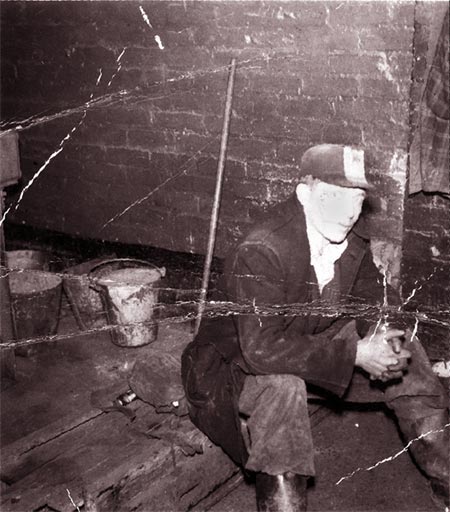

George Evans waiting to go on shift at Banwen colliery

Glo: 'N C bloody B' [PDF 7 MB]

The often callous and brutal treatment of coalminers over the years by both mine owners and management had nurtured a contempt that bordered on hatred. There were three British miners killed every single working day at the time.

So there was genuine rejoicing.

The National Coal Board standard flew proudly at every pithead, the NCB gold logo on a blue field. Only thirteen years earlier 266 miners, had been burnt to death in a north Wales pit. Only 16 bodies were ever recovered and no one properly brought to book. So the rejoicing was truly heartfelt in every coalfield on this island.

No one expected miracles from nationalisation but people became slowly aware of a giant incompetence, a kind of disjointed progress to somewhere, but no one knew exactly where.

One instance that I witnessed was when I was standing in for the underground engine driver in the Eighteen Feet seam. The rope on the main winding engine was about an inch and half in diameter and perhaps about a mile long. The manager, John Williams, was having a heated argument with some blokes from HQ. They wanted to replace the existing rope with a much thicker longer rope.

The new rope was fitted and proved to be too heavy for the weight of the journey (train of trams) to pull the length of the drift. What it cost to put that stupid blunder right goodness only knows. And that sort of crack-brained, hugely expensive blunder was happening a dozen times a day, in every coalfield in the country.

One or two of the colliers were over seventy years of age but filling as much coal as most and earning a tidy wage. We came out one Thursday off afternoon shift and picked up our pay dockets. The old timers had an envelope attached to theirs with a crude little note inside telling them they were on 14 days notice. No pension, no redundancy, nothing - and one or two of the old chaps had started work at 13 years of age!

John Williams had the old men brought back for a day, signed them on and kept them in the canteen until the end of the shift. That meant that the old fellers qualified for one pound a week colliery pension.

I became disgusted with the behaviour of the National Coal Board. Men had struggled over the years to bring about nationalisation - they had even gone to prison!

With each day that passed it became more and more apparent that trying to run the coal industry of Britain from a posh address in Belgravia wasn't working. Everywhere you looked there was disorderliness in planning and organisation. Still, work went on at the coal face in spite of it all.

With the advantage of hindsight we are now able to see an industry, colossal in size, massively underfunded for many, many years and generally very badly managed.

Maybe if someone had thought of asking, or if someone had had the courage to ask, say the head of Boots the Chemist or the head of Austin Cars to take charge, or demand co-operatives to be set up then perhaps the dream would have become reality.

The one positive thing that the miners got from nationalisation was that health and safety improved out of all recognition.

This article forms part of a booklet in the series 'Glo'produced by Big Pit: National Mining Museum. You can download the booklet here:

Glo: 'N C bloody B' [PDF 7 MB]