Fossil Folklore in the Clore Discovery Centre

, 11 March 2019

The National Museum of Wales is home to the Clore Discovery Centre, a hands-on gallery full of exciting treasures. This gallery offers visitors the opportunity to get up close and personal with hundreds of objects from The Museum’s collections, from whale bones to Tudor fabrics.

I have been working at the Discovery Centre for over two years. As a Learning Facilitator, my role is to help visitors of all ages and backgrounds enjoy and learn about our collections. I help people do this in many ways, including handling the objects (carefully!), examining them up close, making connections between objects, and using supporting materials such as books and toys to find out more.

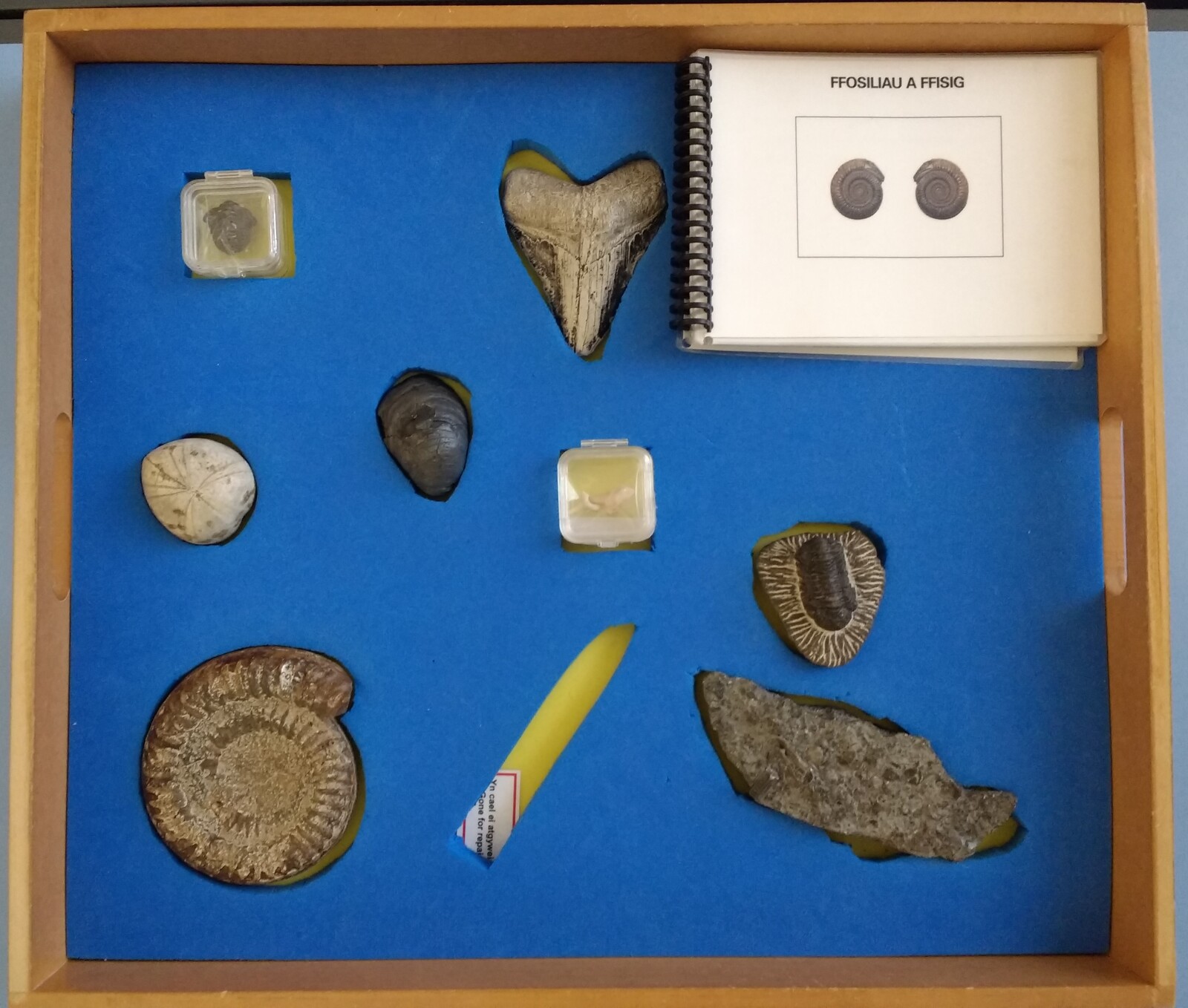

I have become very familiar with our collections, which are housed in drawers with booklets that help us to discover more. Something that I find very interesting about the work of museums is the decisions that are made around how to interpret and talk about objects. One of my favourite drawers illustrates a perfect example of this.

If you were a museum curator and you had a fossil specimen, which collection would you put it into? Maybe the easiest answer is that you would look at it scientifically, and house it in the Geology collection…

However, my favourite drawer, ‘Fossil Folklore’, may help you to think of fossils in a different way, not as science but as part of the stories and local cultures of Britain many generations ago.

When you think about fossils, what do you think about?

Maybe you think about fossils in a museum cabinet, or fossils on a beach such as nearby Penarth (where the odd dinosaur bone has been dug up over the years)!

What would you think if you found a fossil but didn’t know what it was? What if you had never seen one before?

‘Fossil Folklore’ is a drawer in the Clore Discovery Centre that perfectly addresses this question. Over time, people from different countries and cultures have made their own stories about fossils, what they are, and where they come from.

You may be familiar with the ammonite, a round spiral fossil with ridges. The ammonite was a sea creature that lived around the coasts of Britain about 100 million years ago. It is related to the modern nautilus and even squid. Its soft body has decayed with time, and the ridges that we trace our fingers over are the animal’s hard shell.

But what if you found an ammonite and you had never seen one before?

Maybe you would guess that it was a snail, or a long, thin creature curled up into a spiral? Maybe you would think of a story explaining what you thought the ammonite was.

When you look at an ammonite, you can imagine it as a snake curled up into a spiral. For this reason, ammonite fossils were often referred to as “snakestones”. The people of Whitby in Yorkshire have passed down the Legend of St. Hilda to explain their ideas about ammonites and their origin. St. Hilda, a spirited Northumbrian royal, is said to have uttered a mighty prayer and cut off the heads of all the local snakes before turning them into stone. In Christianity, snakes are often seen as symbols of evil, so St. Hilda’s triumph is celebrated. Local craftspeople in Whitby often carved the head of a snake into the ammonite fossils.

One of the reasons that I find this drawer so fascinating is that I love stories. Stories help us to make bonds with each other and to make sense of the world around us. The snakestone story gives us a glimpse into the lives of people living in the Britain many generations ago and helps us to understand how they made sense of their world. Scientific discoveries are always being made, and our understanding of the world is always evolving and changing. Why not come and explore at our Discovery Centre and see if you can find out more about our understanding of the world in which we live?

The Clore Discovery Centre at the National Museum is open at weekends and during school holidays (10am until 4:45pm). The Museum is closed on Mondays.