To Paint a Mistress - two views on Fair Rosamund

Artists have viewed love and adultery very differently at various times in history. Here we look at two very different approaches to "Fair Rosamund", Henry II's mistress, by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1861) and John William Waterhouse (1916).

The Legend

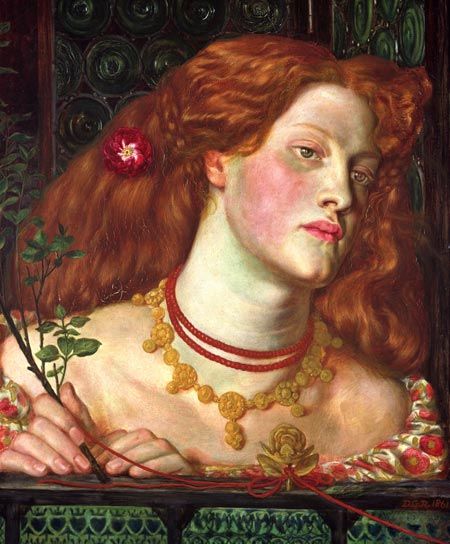

Fair Rosamund (Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1861) appears here behind a balustrade in the royal manor of Woodstock. The sitter, Fanny Cornforth, was a frequent model of Rossetti's. She became his housekeeper after the death of his wife Elizabeth Siddall in 1862. 1861. Oil on canvas.

King Henry II (1154-1189) was married to Eleanor of Aquitaine. He also had a mistress, called Rosamund. According to legend, Henry built Rosamund a palace that could only be reached through a maze. He used a red cord to find his way through the maze and alert Rosamund to his arrival. Eleanor discovered the maze and followed the cord to find her husband's mistress, and murdered her. She offered her the choice of drinking poison or being stabbed.

In reality, Rosamund was not murdered by Eleanor; she retired to a convent where she died in 1176. Eleanor had an excellent alibi for the time of Rosamund's death - she was in prison for treason. Henry had her locked up for supporting their sons in an uprising against him, as seen in the film The Lion in Winter.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti

In Rossetti's version only Rosamund is represented, and the only reference to the story is the red cord. The balustrade on which Rosamund leans is decorated with hearts topped with a crown, in reference to her position as the King's mistress. The rose in her hair refers to her name. The model for this work was Fanny Cornforth, a prostitute who Rossetti met in 1858, and who became his mistress. Rossetti depicts Rosamund as unoccupied; she has no purpose other than to wait for her lover's arrival. Her dress is impractical and revealing, as it slips from her shoulders. She wears decadent jewellery, her face is flushed and her hair is loose. Here we see the stereotypical Victorian concept of the mistress as a non-productive, sexual woman.

John William Waterhouse

Fair Rosamund - John William Waterhouse (1916). The sympathetic treatment that Waterhouse gives to Rosamund is an example of how medieval adultery was often viewed as essentially thwarted love.

1916.

Oil on canvas.

Waterhouse provides an almost opposite depiction of Rosamund in his work, painted 50 years later. In this image we see a fully covered Rosamund kneeling, hands as if in prayer, gazing out of the window awaiting her lover's approach, having abandoned work on her tapestry. The work has the feel of sanctified, married love and not adultery. Waterhouse depicted Rosamund wearing a crown, maybe as an indication that it is not Rosamund's position in the King's affection that Eleanor found threatening but her challenge as a rival queen. If we look away from Rosamund we can see the curtain being parted by Eleanor, the wronged wife, about to enter with murderous intent. Depicting the build up to an event, usually a fatal encounter, was common practice in Victorian art. Here, Waterhouse sets the scene, allowing the audience to imagine the consequences.

The sympathetic treatment Waterhouse gave Rosamund is an example of how medieval adultery was sometimes viewed as essentially thwarted love, for example in the stories of Guinevere and Lancelot or Tristam and Isolde. Marriages in medieval times were made as political alliances rather than love matches. So, when love occurred it inspired sympathy. However, this certainly was not the view taken by Victorian society or by the government. The Irish politician Charles Parnell, for example, was forced out of his position as leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party in 1890 when it became known he had an affair with a married woman.