Adventures in the Mollusca Collections

, 2 November 2015

Perspective of a gap year intern

As a gap year student, one is constantly reminded to find a healthy balance between leisure and useful activities. My favourite kind of balance has always been the kind where one leans as far as possible off the side of the bed without falling off, but I was determined to achieve something more lasting in my first period of freedom from education, perhaps reinvigorating my past interest in life sciences (something which had been left moribund by seven years of National Curriculum biology). Almost on cue, I came upon an internship at the National Museum of Wales, where I could undertake the documentation of a mollusc collection donated to the Museum by an eminent conchologist, an authority on shells, Ted Phorson.

A fantastical microscopic world

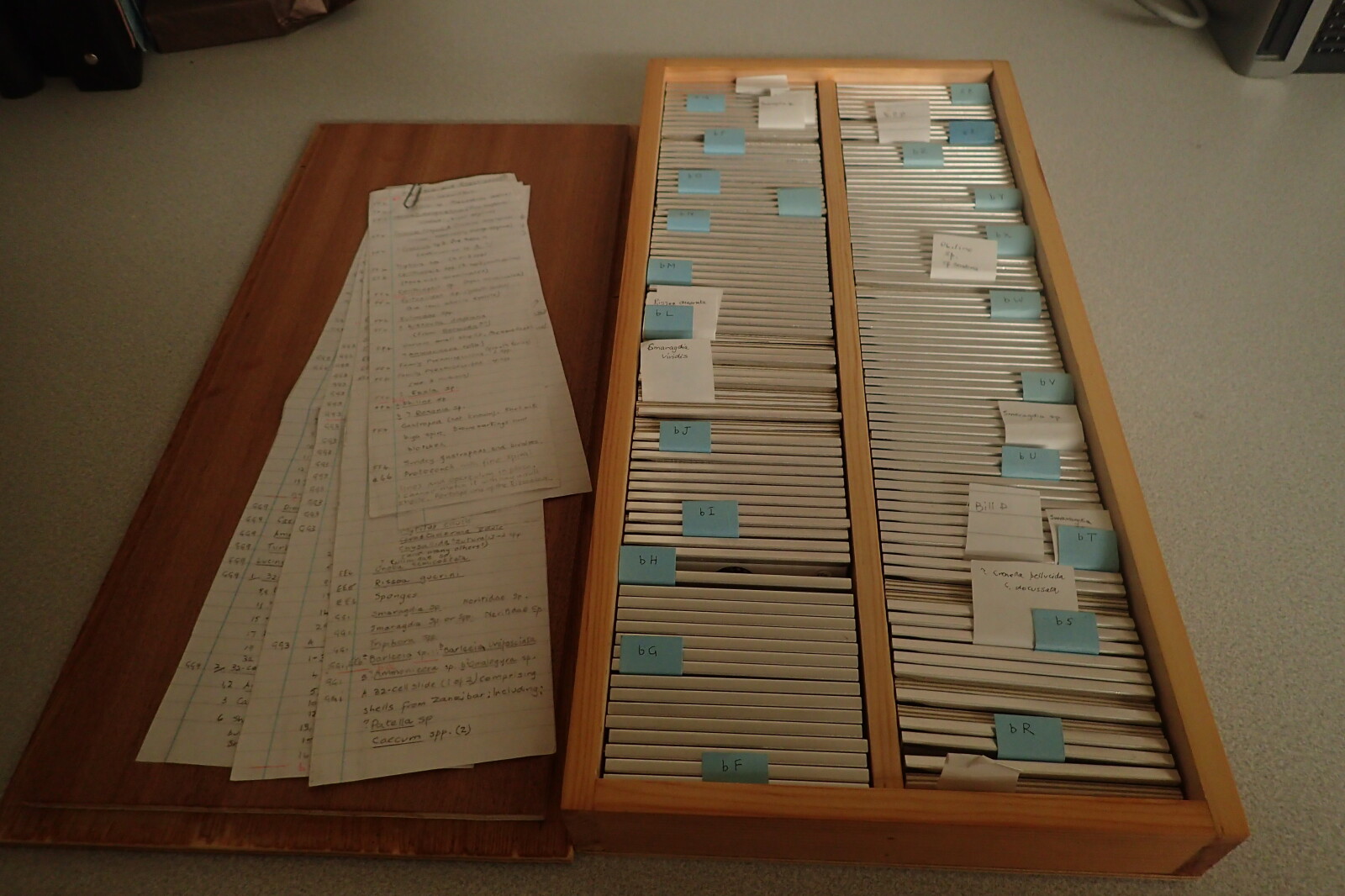

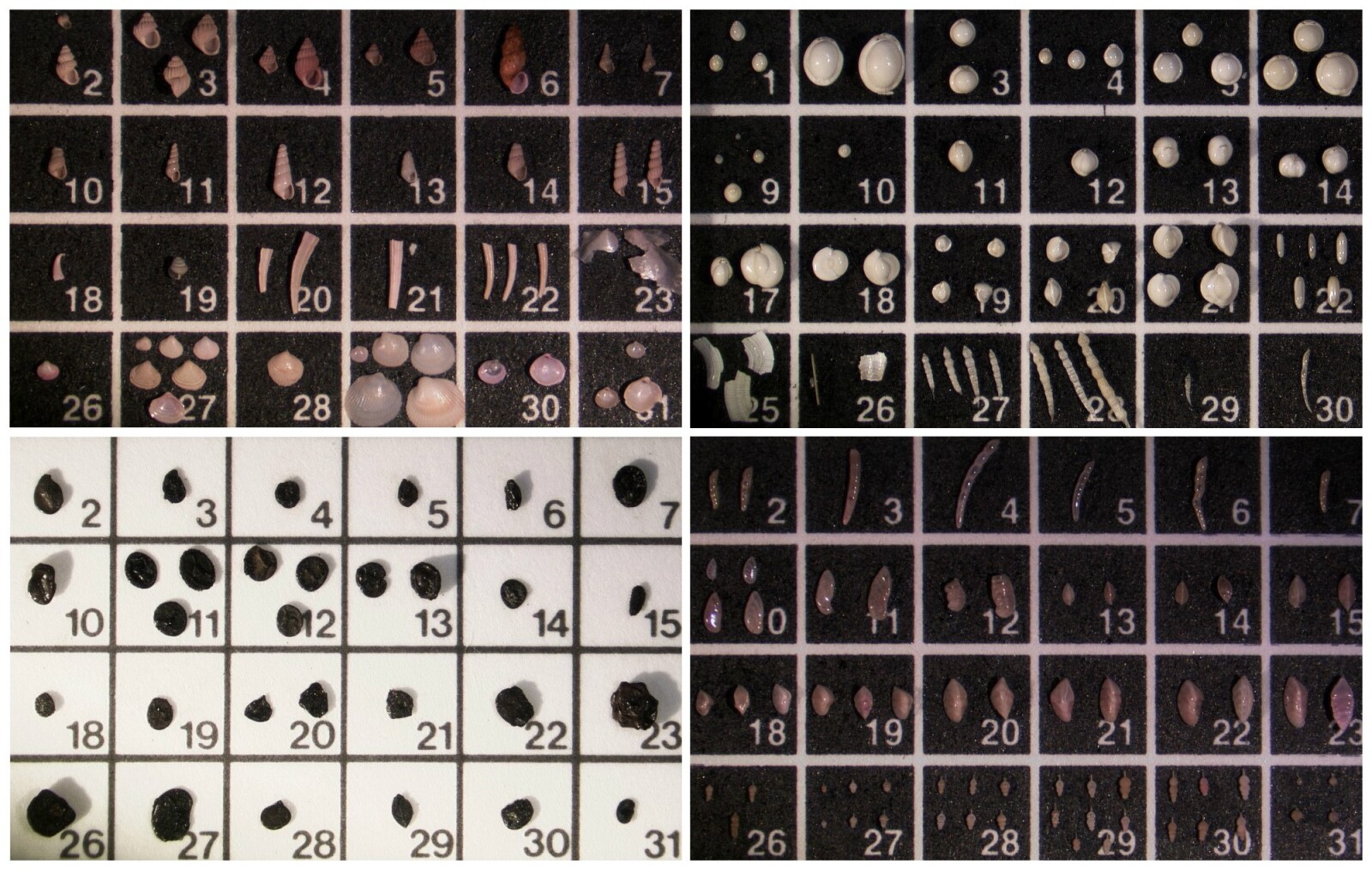

Coming upon Ted Phorson’s excellent yet bewildering mollusc collection after a summer of agreeable idleness was something of a jarring experience, as the complexity and the scale of the task ahead of me was (and still is) vast. The as-yet-unsorted material spans some twenty boxes of varying size, each containing unknown hundreds of regimented specks that, under the lens of a powerful microscope, reveal themselves as minute and fantastical shells marshalled into graded rows by size and species. Each sample of specimens requires a unique record to be written, a process that entails much cross-checking of names and an even greater amount of sifting through the abstruse catalogues and index card systems that accompany the collection. Slides must be cleaned and specimens remounted; some samples of shells from the extreme depths of the North Atlantic, two miles down, needed to be identified from scratch, a daunting task in itself.

A Kafkaesque catalogue

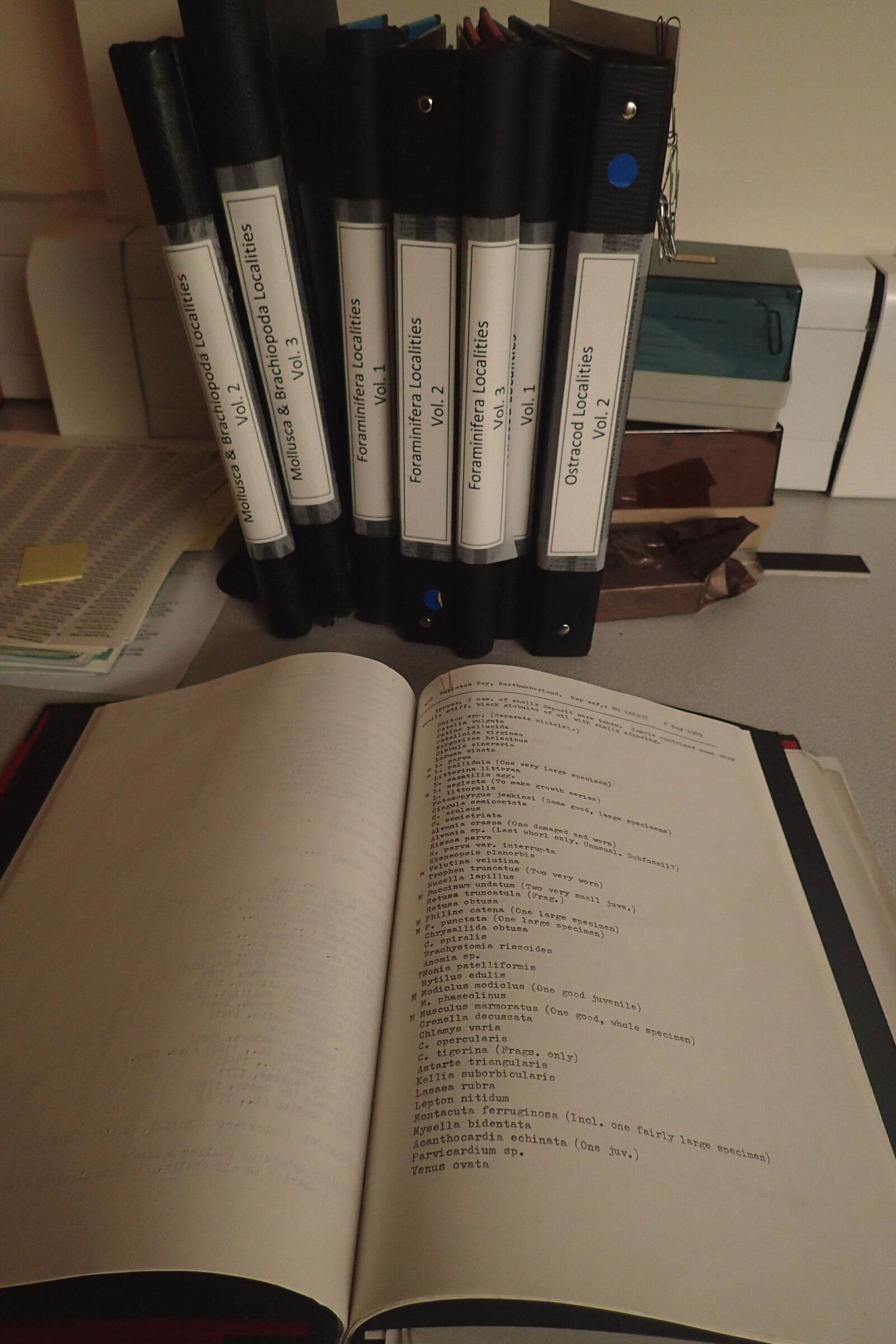

After three weeks amid the boxes I have become familiar with the eccentricities of Ted Phorson’s organisational system, but at the start the reams of papers seemed near-impenetrable. The collections catalogues are a case in point. Containing the full list of every specimen collected at every location visited, the catalogues read from left to right as in any normal book, but the numbering system used to reference specimens to their location runs from right to left: locality Z3 is at the beginning of the series, while a9 is at the end. I have no idea why the list starts (or ends) with a9, as opposed to a1, or why some of the locations have two letters in their code instead of one; over the last weeks I have found myself going in circles from specimen to slide to index card and back again, until all the hand-typed lettering swims together in a surreal wash of Kafkaesque confusion. Despite the seeming chaos, however, the organisation of the collection is impeccable, with every specimen attributable to an exact locality, date, and grid reference (eventually). Any problems I have encountered are all my own, which underlines how crucial documenting the collection really is – with an explicable digital record system, it will be considerably easier for the shells and other organisms to be studied by museum staff and visiting experts.

Phorson’s eccentricities

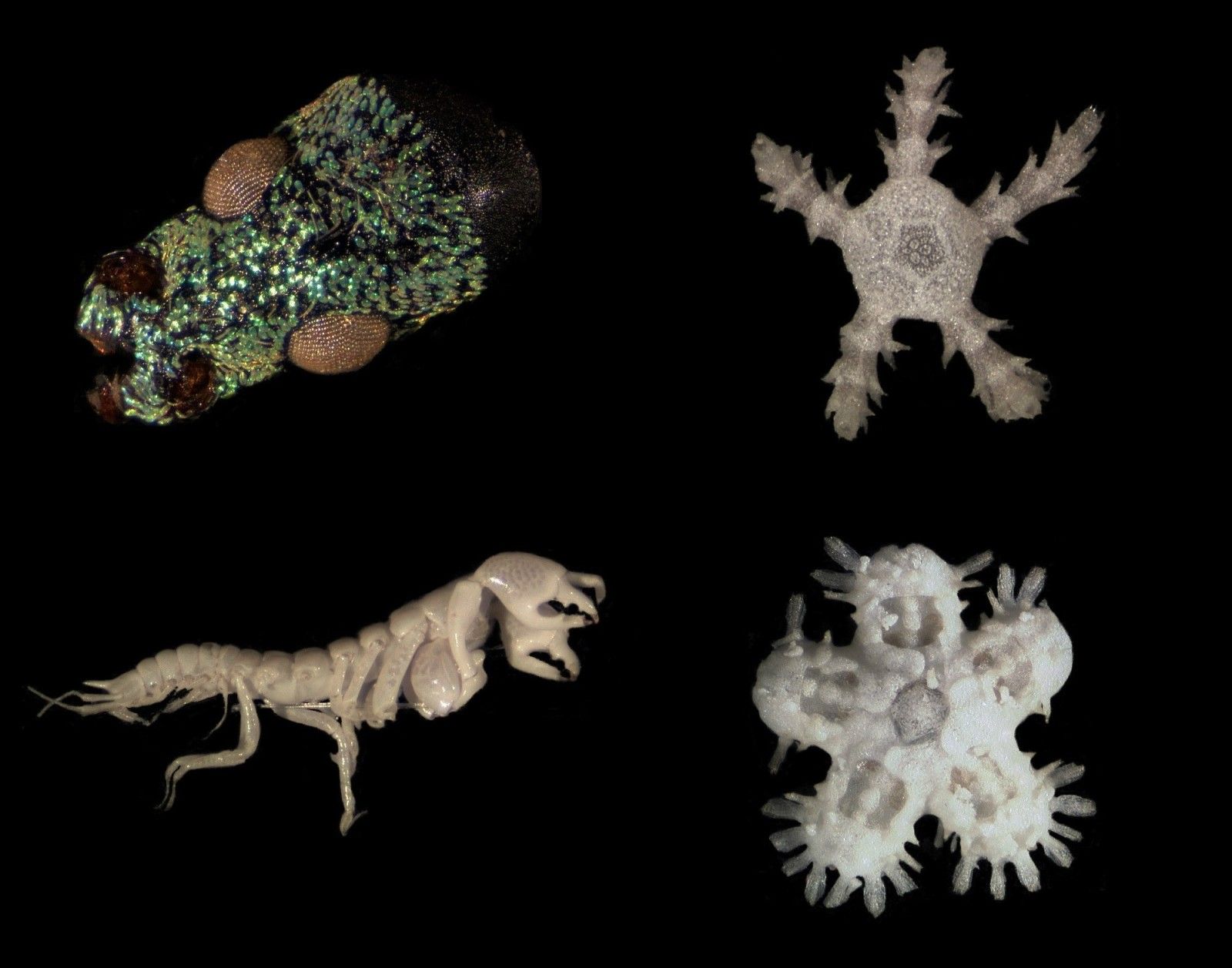

Phorson’s collection is most certainly worthy of study. His technique, of picking through individual samples of sand under a microscope, allowed him to capture the smallest of shells. It was a painstaking process, as a note in the catalogue reveals: “The lower (finer) fraction (of approx. 150gms) was found to contain abundant small molluscs of generally good quality and an abundance of excellent foraminifera and ostracoda… The sorting and picking of this fraction involved many weeks of work”. Not content with mollusc shells alone, Ted Phorson also extracted thousands of foraminifera and ostracods (shelled amoeba relatives and minute crustaceans, respectively), as well fossilised spores from the Coal Measures, fragments of insects, tiny shrimp-like organisms and embryonic starfish; all these minute specimens were affixed to cardboard microscope slides with glue, perfectly aligned for easy examination. Perhaps the most notable slides are those that contain growth series, charting the growth of a shell from the egg upwards; these form an invaluable resource for the identification and study of juvenile and even embryonic shells, a difficult task for which very little scientific literature is available. To compile these physical records of organic growth, Phorson must have worked backwards from the largest to the very smallest, affixing each in perfect order and orientation to create meticulous and minute displays, artful despite their serious scientific bent, exquisite to behold.

We’ve only just begun

My first stint with the collection has lasted for three weeks, and it has been a frustrating, fascinating, and enlightening experience. At the end of it, I have completed some 400 records, a box and a half of slides, and my understanding of mollusc shells and the process of curating a complex and scientific collection is considerably richer. There is a lot more work to be done, however, and I will be coming back to the museum in the new year to continue the task, all things permitting. Thanks are certainly due to my sponsors, the Conchological Society of Great Britain & Ireland, whose kind support has allowed me to eat during my stay in Cardiff, and to the Museum itself, for trusting me with its irreplaceable scientific resources, which I hope I have done justice to.

Learn more about the project here: Curation of a British Shell Collection

Comments - (1)