Stumped by a Spoon

, 20 September 2017

Vibrant discussions are a usual part of the Saving Treasures project and the Amgueddfa Cymru archaeology department.

But I’m not sure we’ve ever had one about a spoon before.

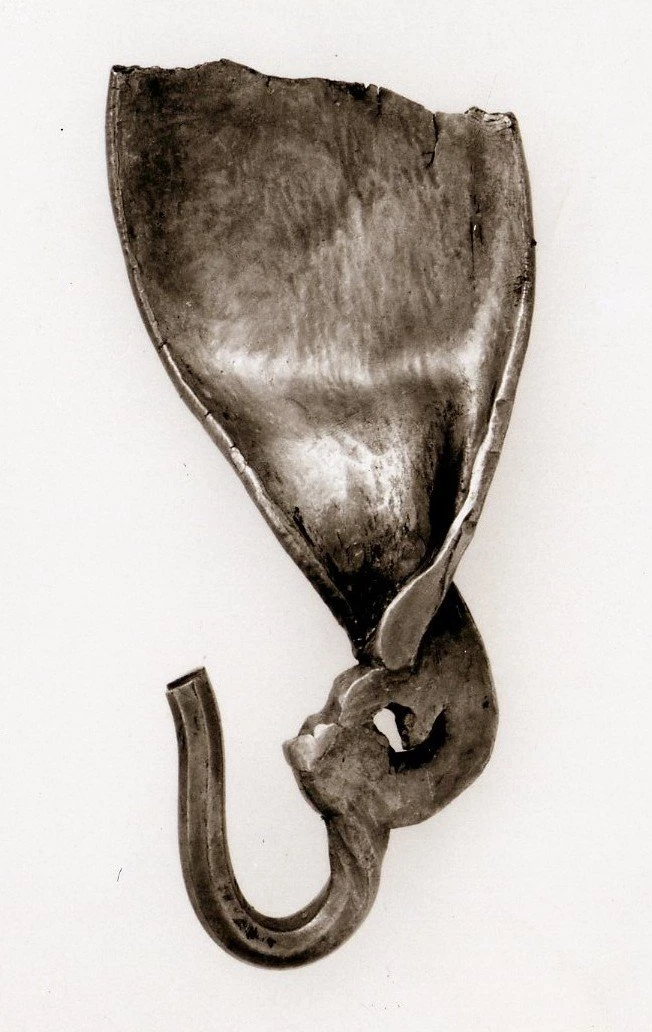

In 2015, a Medieval silver spoon was brought into National Museum Wales; it was found while metal-detecting around Pembroke and can be dated to about the 15th century. The spoon has a rough engraved cross on the underside of the bowl and is in two pieces.

The handle, or stem, has been bent and twisted round, while the bowl has been folded in half and then in half again.

The question bugging us is: why?

Why deform this spoon so greatly?

The deliberate destruction and deformation of objects is not unknown in the Medieval period, though presently we can’t find any parallels for this object.

Many silver coins were, however, damaged for various reasons.

Folding a coin in half, for instance, had a ritualistic function; it was often performed as part of a vow to a saint to cure an affliction or ailment. The coin would then be taken and placed at a shrine. However, Portable Antiquities Scheme data shows that many appear to have been lost or buried in seemingly random locations.

So, we wondered, could the spoon have served a similar function?

Medieval silver spoons were often considered intimate possessions that were carried around much of the time. Dr. Mark Redknap at Amgueddfa Cymru has suggested the engraved cross may represent an ecclesiastical ownership mark. The deliberate destruction of a personal item may have held some significance to the owner, much as a prized possession would today.

Another explanation is that this represents material intended for the crucible, to be remelted and recast into another object. The breaking and recycling of objects is well-known since the Bronze Age. Viking hacksilver involved silver objects chopped and broken either for recasting purposes or as a form of currency, exchanging fragments based on weight.

Fragments of silver spoons are in fact known from hacksilver hoards from Gaulcross, Scotland, and Coleraine, Northern Ireland.

Of course, the Pembroke spoon was buried nearly a 1000 years later than the hacksilver hoards so it cannot strictly be compared. Nonetheless, it is reasonable to think the spoon was broken, folded and twisted into small, compact pieces that would fit more comfortably within a crucible.

We might not find many broken spoons because they were remelted into other objects. The weight of the spoon would comfortably produce other common Medieval objects, such as finger rings, mounts, and pendants.

We will probably never know the reason behind the destruction of this spoon. But it’s always nice to speculate.

Notes and Acknowledgements

The spoon was recently declared Treasure following the Treasure Act 1996 and will be acquired by Milford Haven Museum through the Saving Treasures: Telling Stories project. The full record for the object can be found here: https://finds.org.uk/database/artefacts/record/id/860650

My sincere thanks must go to everyone who engaged with our call for ideas on what this object represents on Twitter. In particular, I’d like to thank Sue Brunning for directing my attention to the hacksilver hoards mentioned in-text.