Meeting Microscopic Marvels

, 28 August 2024

I’m currently studying heritage conservation at Cardiff University, so I wanted to undertake his placement as I have a keen interest in how museums digitise their collections for educational purposes and to increase the accessibility of the heritage they safeguard, and I also wanted to explore how museum collections are used for research purposes.

What are diatoms?

Diatoms are microscopic, single-celled algae that inhabit oceans, rivers, and lakes. They are notable for their intricate cell walls made of silica, which resemble delicate glass shells when viewed under a microscope. These cell walls, called frustules, have unique and complex patterns. Diatoms play a vital role in the environment by performing approximately one-fifth of the total global photosynthesis. This process not only produces a significant portion of the Earth's oxygen but diatoms also form an important part of aquatic food webs, supporting a diverse range of marine and freshwater organisms.

Their importance for research lies in their ability to act as bio-indicators in aquatic ecosystems. Analysis of diatom populations and diversity studies have been used to evaluate human impact on freshwater and marine environments. As bio-indicators, diatoms can be used to assess the levels of organic pollution, eutrophication and acidification of their aquatic environment. Different species have differing tolerance levels of environmental conditions like water pH (the acidity or alkalinity of the water) and nutrient concentrations. Several diatom indices have been developed and are used by the Environment Agency to monitor water quality in UK rivers and lakes.

Analysis of diatom populations can also be used to demonstrate trends over time, as Ingrid’s work on the restoration of water quality of the rivers Wye and Irfon through periodic liming shows (for more details visit https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1470160X20309961#ab010). The same case can be made for historical collections stored in museums, which can provide unique insight into historical diatom populations, and which can be used to infer previous environmental conditions and compare them to those found in contemporary studies.

In addition to their environmental and research importance, diatoms are incredibly beautiful. So much so, that during the Victorian period, they were often assembled into decorative arrangements on microscope slides. For the uninitiated, I would highly recommend searching for images of Johann Diedrich Möller’s work as well as the more contemporary works of Klaus Kemp; they are truly astounding arrangements.

The Placement

Under Dr. Ingrid Juttner’s excellent guidance I learned basic diatom morphology and how to identify Gomphonema species, which typically display asymmetry along the trans-apical axis (i.e. the top and bottom halves are not usually mirror images of each other).

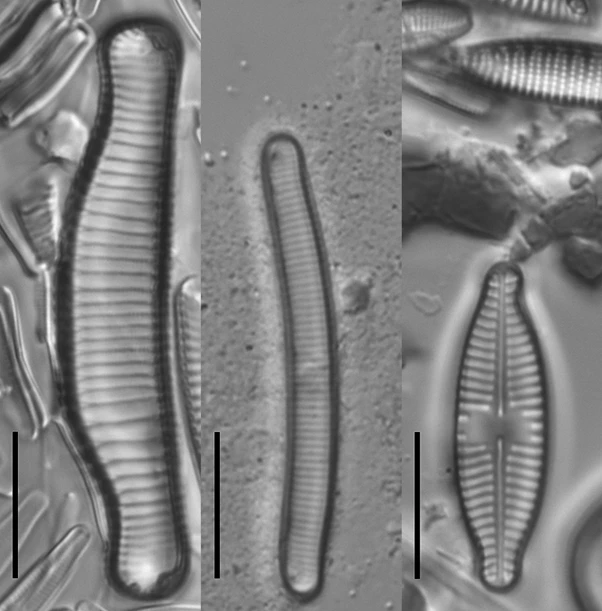

Ingrid took me through the process of diatom analysis in light microscopy, from “cooking” the water samples with hydrogen peroxide to remove organic cell content and preparing the microscope slides, through to photographing, editing and uploading the images to the museum’s diatom website. The photographs featured were taken with a light microscope at x1000 magnification, and measurements (length, width, striae density) were recorded. These images were then edited and prepared as plates to provide an overview of the cell size distribution in the species population. The plates were uploaded to the website with corresponding literature and morphological descriptions.

Some notable species I photographed which are now featured on the website are Eunotia arcubus, Eunotia botuliformis and Planothidium incuriatum.

Overall, my placement within the Lower Plants section has

- Provided me with invaluable insights into scientific and particularly, taxonomic, practices

- Highlighted the role that diatoms play in our natural environments

- Demonstrated how museum collections can and are being utilised for the benefit of science as well as being important repositories for mapping changes in biodiversity.

- Illustrated how projects like the Diatom Flora and Fauna of Britain and Ireland can help create accessible resources for professional and amateur researchers as well as opening up collections to a wider public, who might otherwise be unaware of their existence.

- Finally, this placement has been an opportunity to admire the exceptional beauty of diatoms.

If you would like to know more about the diatom collection at the National Museum of Wales, please see the museum’s Diatom Research page as well as blog posts by Ingrid entitled ‘Scientific expedition to Rara Lake, Nepal’ and ‘Diatom diversity of the Falklands Islands’. I would also highly encourage anyone interested in diatom identification to view the Diatom Flora and Fauna of Britain and Ireland website.

My heartfelt thanks go out to Dr. Ingrid Jüttner for her instruction, her wealth of knowledge and, not least, her conversation. I would equally like to thank the various staff members who coordinated and supported this placement at Amgueddfa Cymru, may there be many more such opportunities.