From Student to Scientist

, 28 July 2021

The next steps in a Professional Training Year

It’s been a little while since my last blog post and since then there has been a lot of exciting things happening! The scientific paper I have been working on that describes a new species of marine shovelhead worm (Magelonidae) with my training year supervisor Katie Mortimer-Jones and American colleague James Blake is finished and has been submitted for publication in a scientific journal. The opportunity to become a published author is not something I expected coming into this placement and I cannot believe how lucky I am to soon have a published paper while I am still an undergraduate.

There are thousands of scientific journals out there, all specialising in different areas. Ours will be going in the capstone edition of the Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington, a journal which covers systematics in biological sciences, so perfect for our paper. Every journal has its own specifications to abide by in order to be published in them. These rules cover everything from the way you cite and reference other papers, how headings and subheadings are set out, the font style and size, and how large images should be. A significant part of writing a paper that many people might not consider is ensuring you follow the specifications of the journal. It’s very easy to forget or just write in the style you always have!

Once you have checked and doubled checked your paper and have submitted to the journal you wish to be published in, the process of peer reviewing begins. This is where your paper is given to other scientists, typically 2 or 3, that are specialists in the field. These peer-reviewers read through your paper and determine if what you have written has good, meaningful science in it and is notable enough to be published. They also act as extra proof-readers, finding mistakes you may have missed and suggesting altered phrasing to make things easier to understand.

I must admit it is a little nerve wracking to know that peer reviewers have the option to reject all your hard work if they don’t think it is good enough. However, the two reviewers have been nothing but kind and exceptionally helpful. They have both accepted our paper for publication. Having fresh sets of eyes look at your work is always better at finding mistakes than just reading it over and over again, especially if those eyes are specialists in the field that you are writing in.

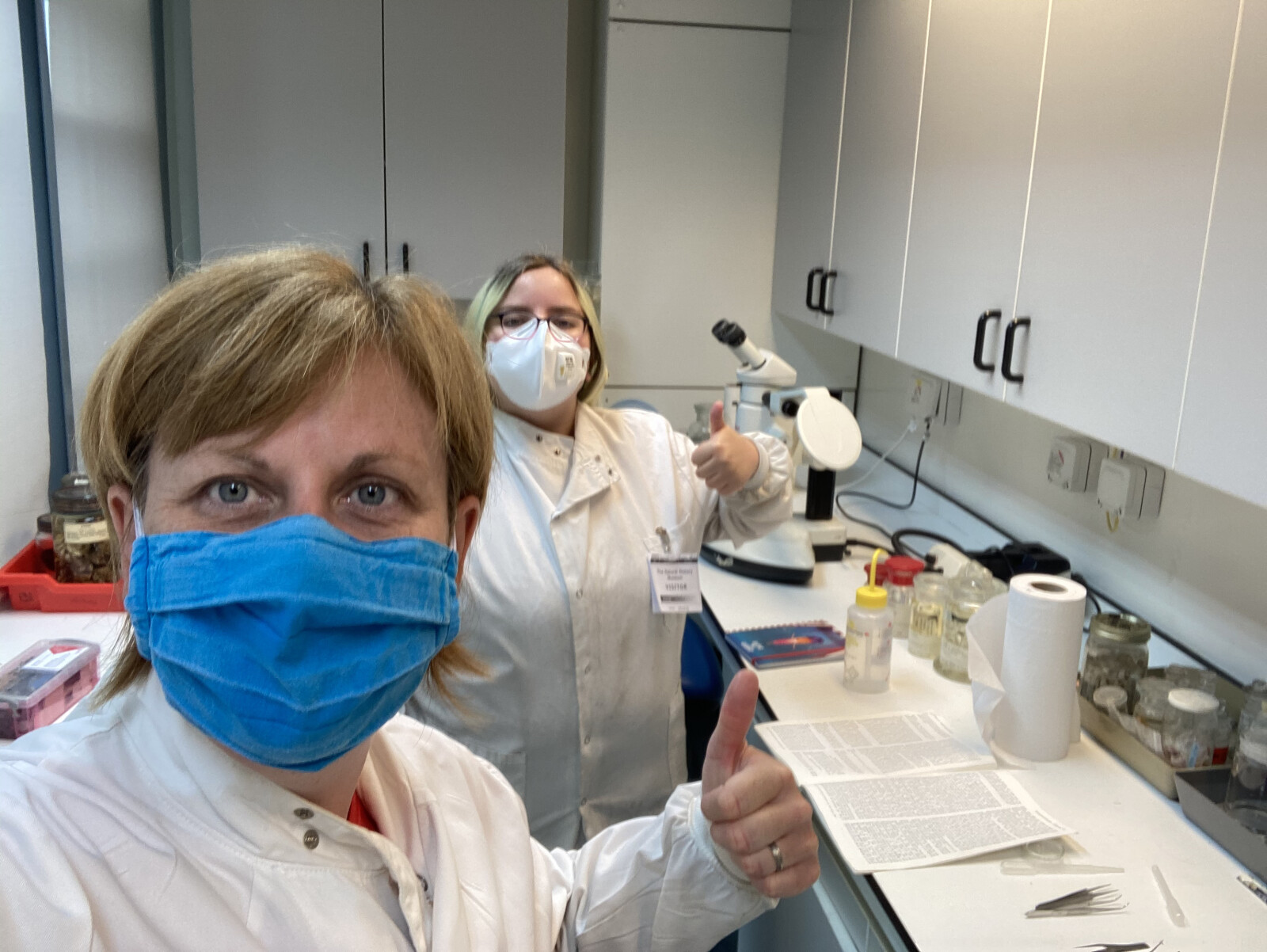

As you would expect, the process of peer-reviewing takes some time. So, while we have been waiting for the reviews to come back, I have already made great progress on starting a second scientific paper based around marine shovelhead worms with my supervisor. While the story of the paper isn’t far along enough yet to talk about here, I can talk about the fantastic opportunity I had to visit the Natural History Museum, London!

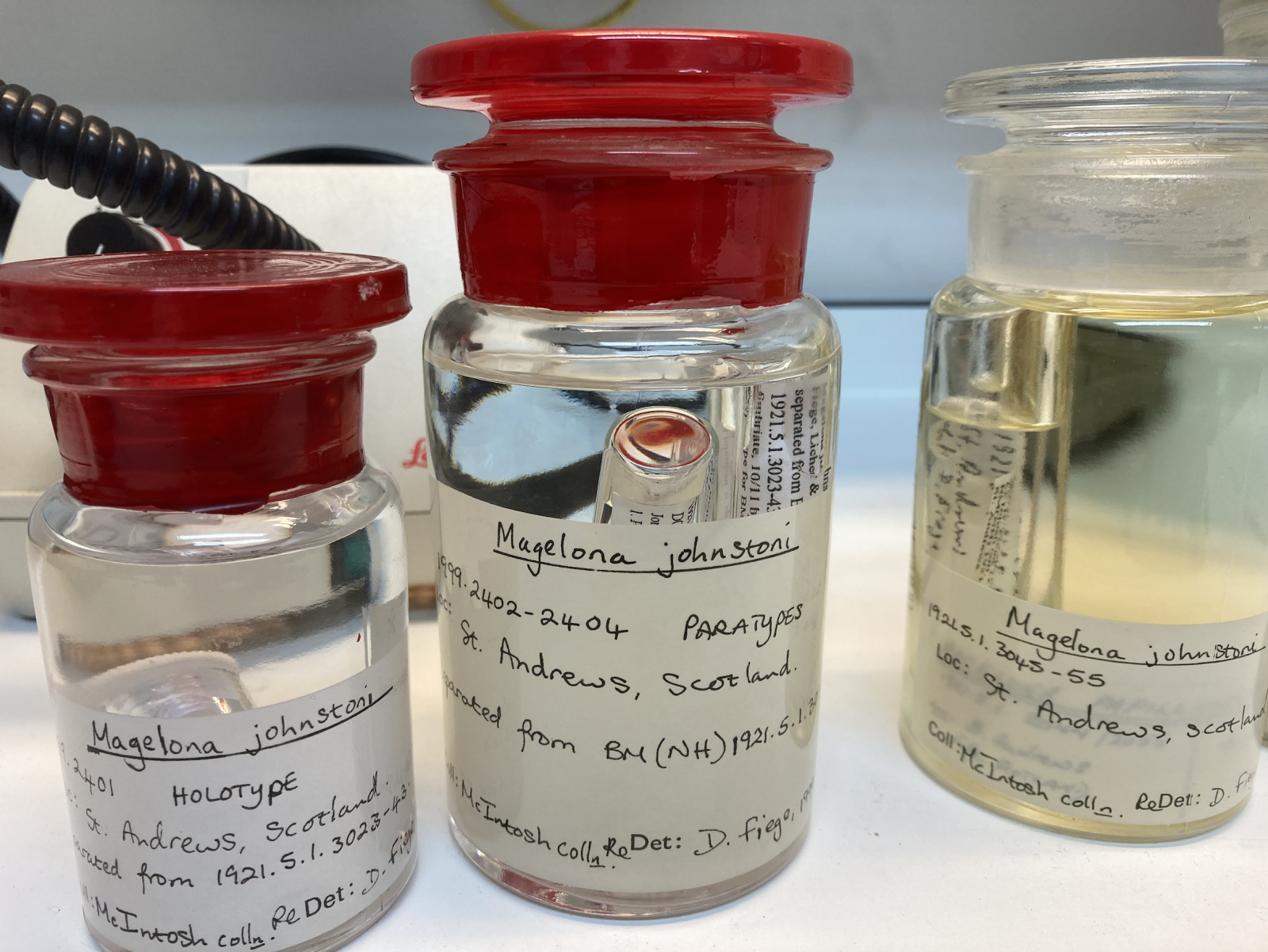

We are currently investigating a potentially new European species of shovelhead worm which is similar to a UK species described by an Amgueddfa Cymru scientist and German colleagues. Most of the type specimens of the latter species are held at the Natural History Museum in London. Type material is scientifically priceless, they are the individual specimens from which a new species is first described and given a scientific name. Therefore, they are the first port of call, if we want to determine if our specimens are a new species or not.

The volume of material that the London Natural History Museum possesses of the species we are interested in is very large and we had no idea what we wanted to loan from them. So, in order to make sure we requested the most useful specimens for our paper, we travelled to London to look through all of the specimens there. We were kindly showed around the facilities by one of the museum’s curators and allowed to make use of one of the labs in order to view all of the specimens. The trip was certainly worth it. We took a lot of notes and found out some very interesting things, but most importantly we had a clear idea of the specific specimens that we wanted to borrow to take photos of and analyse closer back in Cardiff.

Overall, I can say with confidence that the long drive was certainly more than worth it! I’m very excited to continue with this new paper and even more excited to soon be able to share the results of our first completed and published paper, watch this space…

Thank you once again to both National Museum Cardiff and Natural History Museum, London for making this trip possible.