Llys Rhosyr: revealing the past

, 22 April 2015

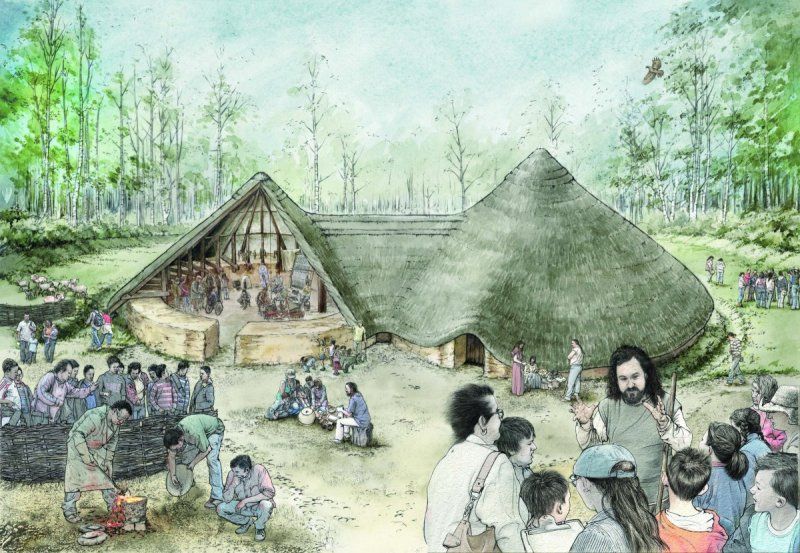

Our 13th century Royal hall is moving forward at quite a pace. At the minute work focusses on the window reveals of the smaller of the two structures, currently known as ‘Building B’. This building could have been the Royal bed chamber (for other contemporary examples feature a chamber and hall within close proximity to each other), but equally it could have been the kitchen, (which would also have been in close proximity to the hall, for who would want to feast on cold food?).

The window reveals are typically Romanesque in style. They are very narrow on the outside, but widen considerably on the inside, in order to maximise the light coming through. The reason for their narrowness is two-fold: small windows are more easily defended and hence were a common feature of more fortified structures such as castles; secondly, as glass for glazing was not always available their size was kept to a minimum in order to reduce the amount of cold air coming in. They will be capped by a level stone lintel, but likewise they could have been capped with an arch – as both methods were common at this time. Wooden shutters will be installed and closed at night, so that visiting schoolchildren will be warm when sleeping over.

Off-site work has begun on saw-milling oak boughs into timber for the roof trusses. Getting a long square-edged timber out of a log takes some considerable skill. The large band-saw can only cut straight lines, therefore the log has to be positioned correctly before every pass. It has to be adjusted up and down, as well as from side to side, because one cut at the wrong angle would negatively impact the following cuts, and render the timber unusable.