International fame for Wales's 'National Fossil'

A specimen of Paradoxides davidis from Porth-y-rhaw, x 0.75. Amgueddfa Cymru collection

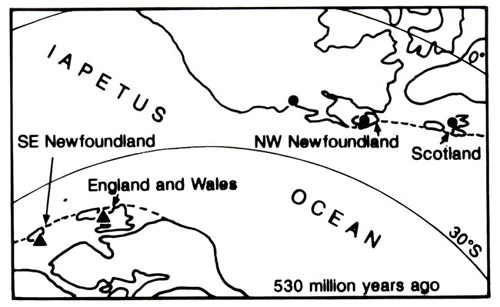

Stage one in the evolution of the north Atlantic area. Triangles indicate areas yielding 'Welsh' trilobites, with dots showing 'North American' forms.

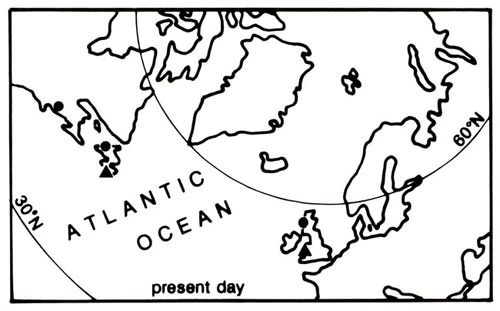

Stage two in the evolution of the north Atlantic area. Triangles indicate areas yielding 'Welsh' trilobites, with dots showing 'North American' forms.

Stage three in the evolution of the north Atlantic area. Triangles indicate areas yielding 'Welsh' trilobites, with dots showing 'North American' forms.

Fossil collecting around the St. David's Peninsula, Pembrokeshire

In 1862 the well-known palaeontologist J W. Salter was collecting fossils in south-west Wales as part of his duties for the British Geological Survey. While examining coastal exposures by boat around the rocky St David's peninsula, Salter one day landed in a small inlet called Porth-y-rhaw, in the mistaken belief that it was Solva Harbour, only a short distance to the east.

His mistake turned out to be extremely lucky, because in the rocks of Porth-y-rhaw, he discovered the remains of one of the largest trilobites ever found (over 50 cm long), and this discovery ensured that the locality became established as a classic and well-known source of fossils.

Life in the sea hundreds of millions of years ago

The dark mudstones exposed there were deposited in an ancient sea some 510 million years ago, during what is now called the Cambrian Period - the name reflecting the fact that rocks of this age were first recognised and named in Wales by the early 19th-century geologists.

Porth-y-rhaw is one of a small number of sites in Wales where Cambrian fossils are reasonably well-preserved and easy to find, and in addition to Salter's giant trilobite it also yields many other kinds of these extinct marine arthropods of more usual dimensions (2-3 cm long).

A National fossil for Wales

The formal scientific name given by Salter to the giant trilobite is Paradoxides davidis, named after his friend David Homfray, an amateur fossil collector from Porth-madog. This trilobite is now one of the best-known from Britain, and is illustrated in numerous publications; choice specimens are among the prize possessions of many of our major museums, including the National Museum of Wales. Indeed, if there were to be a 'national fossil' for Wales, Paradoxides davidis would be the prime contender.

Worldwide Fame

Many specimens of Paradoxides davidis also occur in the Avalon Peninsula of south-east Newfoundland, in rocks of exactly the same age as those exposed in Porth-y-rhaw.

In this context, it is important to understand that in the Cambrian Period, the distribution of continents and oceans was quite different from that of the present day. At that time, Wales, England and south-east Newfoundland all lay on the southern side of an ancient ocean, called Iapetus, and were separated from Scotland and north-west Newfoundland, as shown on the accompanying map.

While the same kinds of trilobites occur in Wales and south-east Newfoundland, quite different ones are common to Scotland and north-west Newfoundland, providing evidence that they once formed parts of different continents.

Snowdon is born

Around 480 million years ago, movements in the Earth's interior caused the ancient Iapetus Ocean to narrow gradually and finally to disappear as two continental masses collided, leading to the formation of a high mountain range of which the Welsh, Scottish, Scandinavian and Appalachian mountains are the present day remnants.

The new Atlantic Ocean

Much later in Earth history, between 200 and 65 million years ago, the two continents began to pull apart again, leading to the formation of a new ocean that was to become the present day Atlantic. However, the new split was not along quite the same line as that along which Iapetus had closed, and left south-east Newfoundland with its 'Welsh' trilobites anchored to the rest of Newfoundland and North America, with Scotland and its 'North American' trilobites attached to the rest of the British Isles.

The occurrence of these same trilobites in areas that today are geographically remote emphasises the need for geologists to study fossils far afield if they are to interpret fully the ancient history of their own local pieces of the Earth's crust.