Posy Rings

Posy ring from Henllys

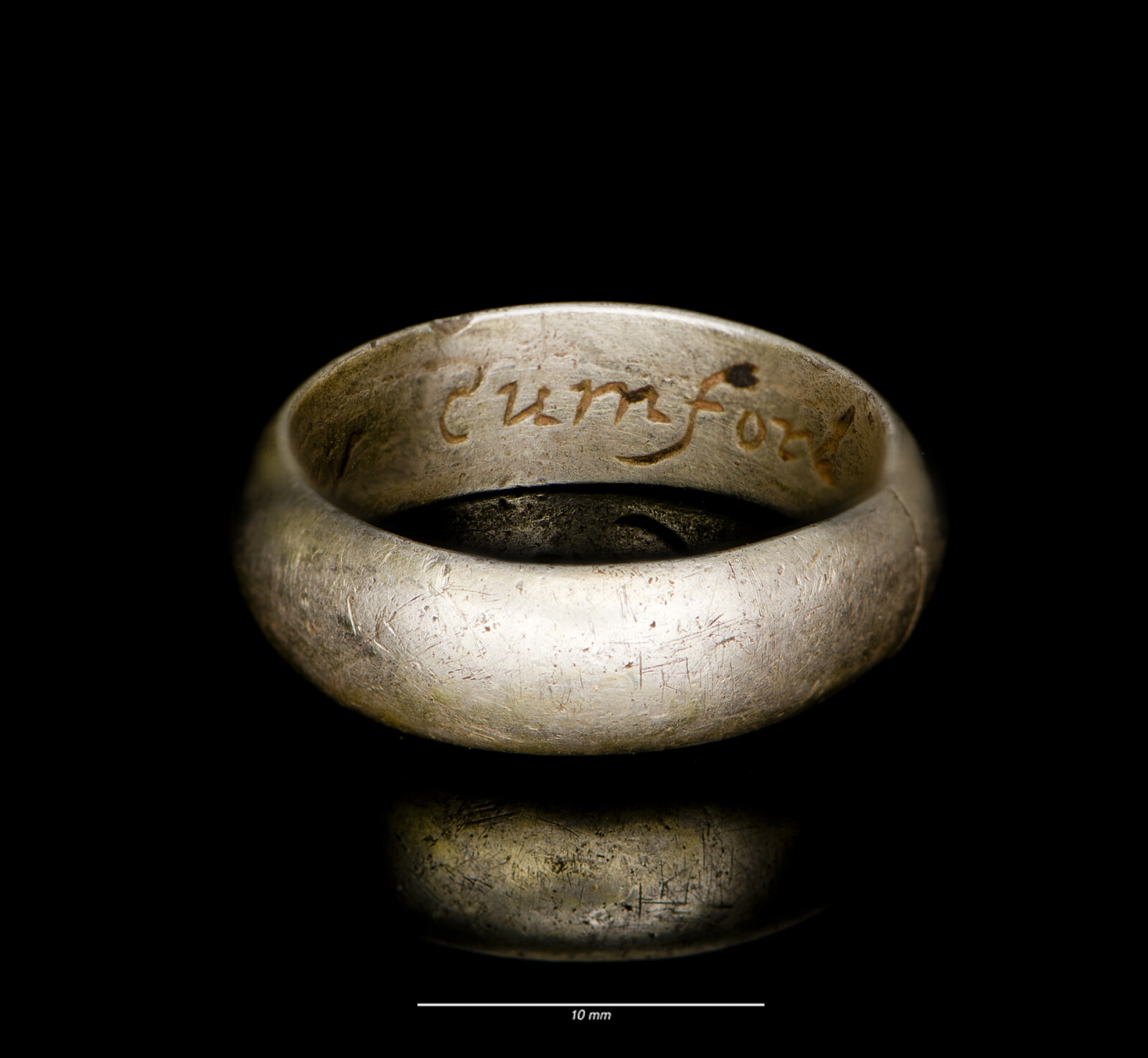

Posy ring 'God is my Cumford'

Posy Ring form St Dogmaels

The exchanging of rings as tokens of love is not just a modern practice. Posy rings, inscribed with mottoes or short phrases indicating love or fidelity have been popular from the Middle Ages. Though we now associate the giving of rings with the formal occasion of an engagement or wedding, historically posy rings may have been given at any stage of the relationship, and by either partner. They may be plain bands, or decorated in a variety of ways, but their most important aspect was not so much their outer appearance as the carefully chosen message they contained, which was intended as a personal and constant reminder of the giver’s feelings towards the recipient. Some mottoes are in Latin or French, the latter being associated with chivalry and courtly love, but many of those discovered recently by metal detectorists in Wales have English phrases, most of which play on the theme of fidelity and constancy.

A particularly delicate and decorative example, from the late 16th or early 17th century was discovered in August 2013 by Mr Simon Harrison at Henllys, Monmouthshire. Made of linked gold roundels and hearts filled with red, white and green enamel, the inner surface is inscribed with the words ‘My ♥ is onely yours’. Several other rings, four of which have been recently acquired by the Saving Treasures; Telling Stories project for national and local collections, have inscriptions communicating a variety of sentiments, but not all of them are as straightforwardly romantic as the Henllys example. ‘Forget not the gift’ urges the decorated gold ring found near St Dogmael’s, Pembrokeshire, by Mr Tom Baxter-Campbell in June 2011. This suggests that the ‘gift’ of the ring should act as a reminder of the giver: was he or she about to go away? Was there perhaps some doubt that their feelings might not be returned?

A similar ring, also of gold and dated to the late 16th or early 17th century, found at Llantwit Major by Mr David Hughes in April 2013, bears the enigmatic legend ‘Such is my love.’ The precise meaning of this phrase is unclear, but the intention could be that the giver’s love is enduring and precious, like gold, and eternal, a quality associated with the ring’s shape, which has no beginning and no end. Presumably the receiver of the ring understood exactly how to interpret the message.

Although posy rings are associated with messages of love, some examples recently discovered in Wales strike a decidedly sober tone. A late 17th or early 18th century silver-gilt ring found near Caerphilly in June 2013 by Mr T.M. Davies, and now in the collection of the Winding House Museum in Tredegar, looks very much like a modern plain wedding band. On the inner surface is the inscription ‘Keep faith tell [till] death’, a rather sombre sentiment somewhat out of step with lighter modern endearments but utterly in keeping with past understandings of the indissolubility of marriage. In an age when divorce was virtually impossible, marital relationships were for life. Not all posy rings carried statements of love, however: a plain silver-gilt band discovered at Llangibby, Monmouthshire, by Mr Glen Flynn in 2012 declares ‘God is my cumford [comfort]’. Does this suggest that the ring was given at a time of personal distress, sorrow or illness for the wearer, or does it merely reflect their personal piety?

A notable feature of all of these rings, as with some of those featured below, is that these mottoes are inscribed on the inside, rather than the outside, of the band. But why would these ardent suitors want to hide their declarations of love instead of setting them where all could see? The likely reason is that the messages were private, intended to have significance only for the giver and for the wearer, who bore the message next to the skin, emphasising the intimacy of the relationship.

Comments - (3)

Dear Ian,

Thank you for your email; I’m glad you enjoyed the article.

Your question is an interesting one. I am not aware of any rings from this period with inscriptions in Welsh, which, when I think about it, is not easy to explain. Welsh appears on medieval seal matrices and on post-medieval church monuments, among other things, so there’s no reason why it shouldn’t be used on rings, but I’ve never come across it. Mark Redknap may be aware of some examples, so I will ask him and get back to you if he knows of any.

All the best,

Dr Rhianydd Biebrach, Saving Treasures Project Officer