Coins from Edward the Confessor and William the Conqueror found in Monmouth field

Part-cleaned and fully-cleaned coins. Each coin measures about 2cm (0.75 inches) across.

Penny of Edward the Confessor struck by Estan at Hereford, around 1060. Measures 1.9cm (0.75 inches) across.

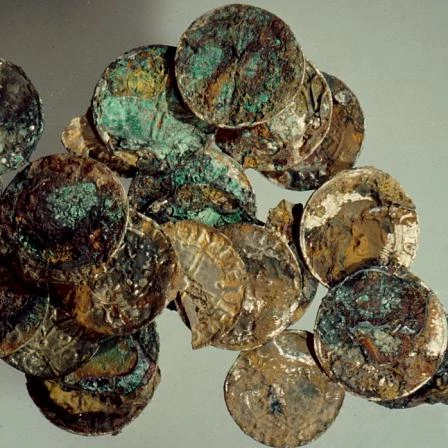

Part of the Abergavenny hoard as discovered.

Traces of the cloth bag, preserved in the mineralization. This image shows some of the stitching.

An updated version of this article has been published.

In April 2002 three metal-detectorists had the find of their lives in a field near Abergavenny, Monmouthshire: a scattered hoard of 199 silver pennies.

The hoard included coins of the Anglo-Saxon king Edward the Confessor (1042-66) and the Norman king William the Conqueror (1066-87). The hoard probably pre-dates the founding of Abergavenny near by in the 1080s.

The hoard was heavily encrusted with iron deposits, including traces of fabric, suggesting that the coins had originally been held in a cloth bag. It is not clear whether they had been deliberately hidden, or simply lost. Either way their owner was the poorer by a significant amount: sixteen shillings and seven pence (16s 7d, or £0.83p) would for most have represented several months' wages.

Minting coins

Anglo-Saxon and Norman coins form an unique historical source: each names its place of minting and the moneyer responsible. People had easy access to a network of mints across England (there were none in Wales) and every few years existing money was called in to be re-minted with a new design. The King, of course, took a cut on each occasion.

The Abergavenny hoard includes 36 identifiable mints, as well as some irregular issues which cannot at present be located. Coins from mints in the region, like Hereford (34 coins) and Bristol (24), are commonest, outweighing big mints such as London (19) and Winchester (20). At the other end of the scale there are single coins from small mints such as Bridport (Dorset), or distant ones such as Thetford (Norfolk) and Derby.

Hoards from western Britain are rare, so the Abergavenny Hoard has produced many previously unrecorded combinations of mint, moneyer, and issue.

We shall probably never know quite why these coins ended up in the corner of a field in Monmouthshire but, as well as expanding our knowledge of the coinage itself, they will cast new light on monetary conditions in the area after the Norman Conquest.

Conservation

The coins were found covered in iron concretions and many of them were stuck to each other. This disfigured the coins and obscured vital details. Removing this concretion with mechanical methods, such as using a scalpel, would have damaged the silver, and chemicals failed to shift the iron.

The solution to the problem was found in an unexpected, but thoroughly modern tool - the laser. A laser is a source of light providing energy in the form of a very intense single wavelength, with a narrow beam which only spreads a few millimetres.

As laser radiation is of a single colour (infrared light was used in this case) the beam will interact intensely with some materials, but hardly at all with others. This infrared source was absorbed better by the darker overlying iron corrosion than by the light silver metal.

The laser was successful at removing much of the iron crust, but initially left a very thin oxide film on the surface. When this was removed, the detail revealed on the underlying coin was excellent; it was possible to see rough out and polishing marks transferred to the coin from the original die, as well as the inscribed legend.

Background Reading

Conquest, Coexistence, and Change. Wales 1063-1415 by R. R. Davies. Published by Oxford University Press (1987).

The Norman Conquest and the English Coinage by Michael Dolley. Published by Spink and Son (1966).