Dinorwig '69: End of the line for one of the largest slate quarries in the world

End of the line

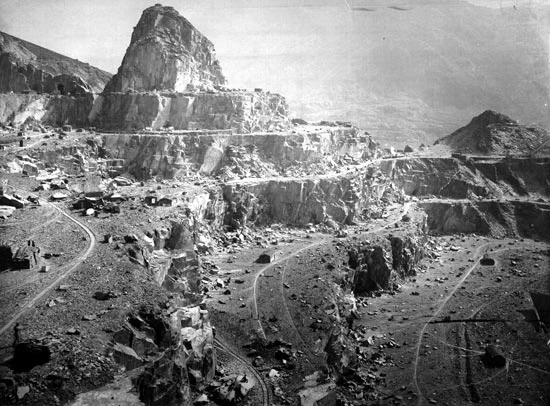

Dinorwig Quarry. With the dawn of the Industrial Revolution slate was used to cover the roofs of factories and houses throughout Britain, mainland Europe as well as towns in North America and other parts of the world.

On 22nd August 1969 silence came to Dinorwig Quarry. After almost 200 years of hard toil, the quarry was closed and the men were sent home for the last time.

Not only did 350 men lose their jobs but a quarrying community and a way of life that had existed since the 1780's changed forever.

Everyone in the area had lived in the shadow of Dinorwig Quarry all their lives. Everyone had a father, grandfather, husband, uncle or brother who had worked there. A century earlier, closure would have been unimaginable. Dinorwig was one of the two largest slate quarries in the world ‐ and, along with its neighbour at Penrhyn, Bethesda, could produce more roofing slates in a year than all other combined slate mines and quarries world-wide.

Old quarrying methods

This is a clip from the first audio film in Welsh, Y Chwarelwr (The Quarryman), made in 1935. There is no sound in this piece as only some of the film survived, and the sound was recorded on disks separate from the film itself. © Urdd Gobaith Cymru.

Why did the quarry close?

Quarrymen at Dinorwig Quarry.

Dinorwig Quarry's demise didn't happen overnight. Things hadn't been going well for a number of years for various reasons:

- there was less demand for slate in the UK during the 20th century;

- Welsh slate was expensive compared to roofing tiles and slate from overseas;

- the quarry owners were competing against one another for a share of a fairly small market;

- Dinorwig Quarry hadn't been developed effectively. The slate that was easy to get at had been quarried by the 60s and investment was needed to develop further. The quarry owners didn't have the money for this investment. One of their mistakes was to invest heavily in Marchlyn Quarry, but this part of the mountain didn't make them any money. There was no slate worth working there at all;

- by the late 1960s, the quarry depended on orders from France to survive. In July 1969, these orders stopped. The final nail in the coffin.

By the 1960s, the slate industry in general was facing an uncertain future.

What next?

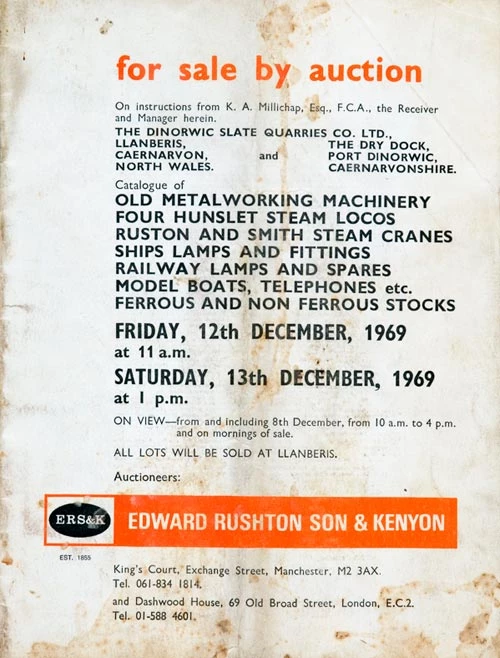

Dinorwig Quarry auction catalogue. December 1969

Many of the 350 who lost their work found other jobs, some locally, at Ferodo and Peblig Mills, others further afield at Dolgarrog, Trawsfynydd and Holyhead. Others went even further to find work — to Corby, the relatively new steel town in Northamptonshire.

October and December, 1969 saw the auctions — selling off anything and everything that was worth carrying from the workshops. Fortunately for us, here at the Museum, Hugh Richard Jones, Dinorwig Quarry's Chief Engineer, ensured that not everything was sold. With the help of like-minded visionaries, he was instrumental in ensuring that the water wheel wasn't broken up and taken away and in preserving the machinery in the workshops.

Three years following the closure of Dinorwig Quarry, in 1972, the National Slate Museum was opened at Gilfach Ddu, and Hugh Richard Jones became its first manager.

Comments - (2)

Dear Judith,

Thank you very much for your enquiry. I have forwarded it to the relevant curator at St Fagans National Museum of History, who will be in contact with you.

Best wishes,

Marc

Digital Team