Madness not to stay safe around Mercury

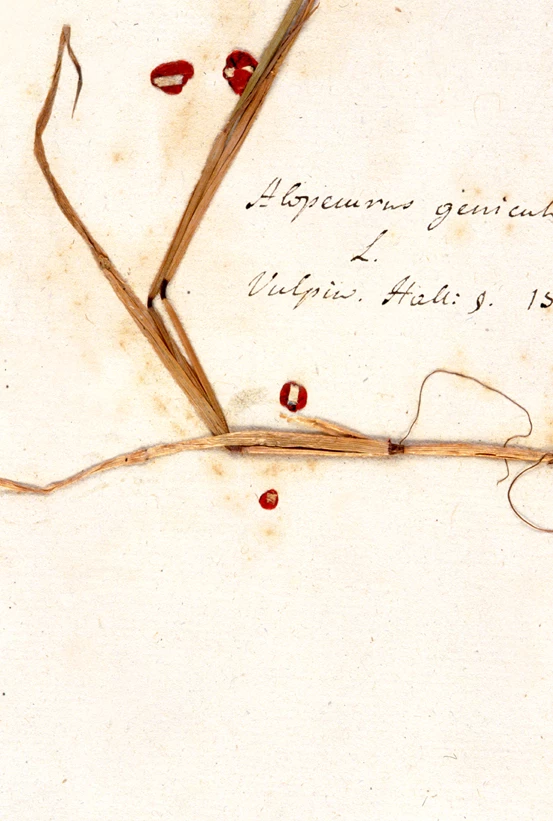

Figure 1 Image of a section of a specimen sheet belonging to the 3rd Earl of Bute’s herbarium c. 1770. The paper sheet is not providing any clues as to whether this sheet has been treated or not. The brown stains are natural breakdown products of the plant.

Figure 2 The same herbarium sheet under UV exposure. The grey discolouration is typical of mercury and the bright splashes are indicative of aqueous mercury applications.

Figure 3 Using the UV scanning device.

Natural history collections are susceptible to deterioration from pests and moulds and so historically, chemicals have been applied to safeguard these collections for the future. The most common chemical application to botanical specimens was Mercuric chloride (Corrosive sublimate). Mercury has helped to preserve specimens up until the present day, but these treatments leave a legacy - salts of mercury are not only toxic to pests, but also to people.

'Mad as a hatter'

In the 19th century, the felt-hat industry commonly used mercuric nitrate to cure the felt. The wearer and the hat maker were then exposed to mercury which is now known to attack the central nervous system and affect the brain. The unusual behaviour attributed to hat makers, due to the mercury poisoning, gave rise to the term ‘Mad as a hatter’ and probably fuelled Lewis Carroll’s imagination for his ‘mad tea party.’

The main problem encountered with these treatments is that they are hazardous to health but largely imperceptible to the human eye (Fig. 1).

Research conducted at the National Museum Wales department of Conservation, uncovered that some of the 600,000 herbarium specimens housed within the collections were contaminated with mercury. This could pose a potential risk to the health of staff members and visitors to the collections, unless addressed. It was important to be able to establish which sheets had been treated, what the chemical was and how much was present. To do this in the usual way would have involved specialist chemists, expensive analytical equipment and years of work; an expensive and timely process.

Continuing research into this issue by Dr Vicky Purewal, the botanical conservator at the National Museum Wales, uncovered that chemical processes are accelerated by mercury in the ageing papers, providing tiny clues to the presence of mercury. By devising a specific novel technique, these tiny clues can be translated into real information. This technique does not require expensive analytical equipment, all it needs is a simple hand held UV-A lamp. The Ultra violet radiation causes certain chemical processes in the paper to fluoresce a definite colour providing a positive response to the presence of mercury (Fig.2).

This research by the museum has been vital in developing a rapid technique in identifying contaminated collections (Fig.3). It has helped provide information on the historic treatments that the specimen has undergone and as a result helped to safeguard the health of staff members and visitors to the herbarium. As a result the collections can be separated into treated and non-treated material. The contaminated collections can then be handled appropriately and re-mounted removing a large amount of the contamination from the herbarium environment. DNA analysis currently carried out by researchers within the NMW herbarium; also find the UV technique extremely efficient at helping to determine whether the collections have been subjected to mercury applications which may interfere with extraction of genetic information.

The impact of this research is two-fold: on professional conservation and curatorial practice; and on the health and safety of the collection users when working within the herbarium. Key institutions such as the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, the Natural History Museum, London and the Royal College of Physicians are just a few of the other organisations that have benefitted from this simple and rapid identification tool developed by Vicky Purewal at the National Museum Wales.