Rediscovering the Past: The Tomlin Archive provides a powerful insight into post-WW2 life

, 25 October 2019

At first glance, The Tomlin Archive helps us to explore the life of John Read le Brockton Tomlin (1864-1954), one of the most highly-respected shell collectors of his time. Alongside Tomlin's extensive shell collection, his correspondence archive holds documents he sent, received and collected, dating from the early 1800’s through to the mid 1900’s. They provide an in-depth look into Tomlin’s life, along with the lives of those he knew.

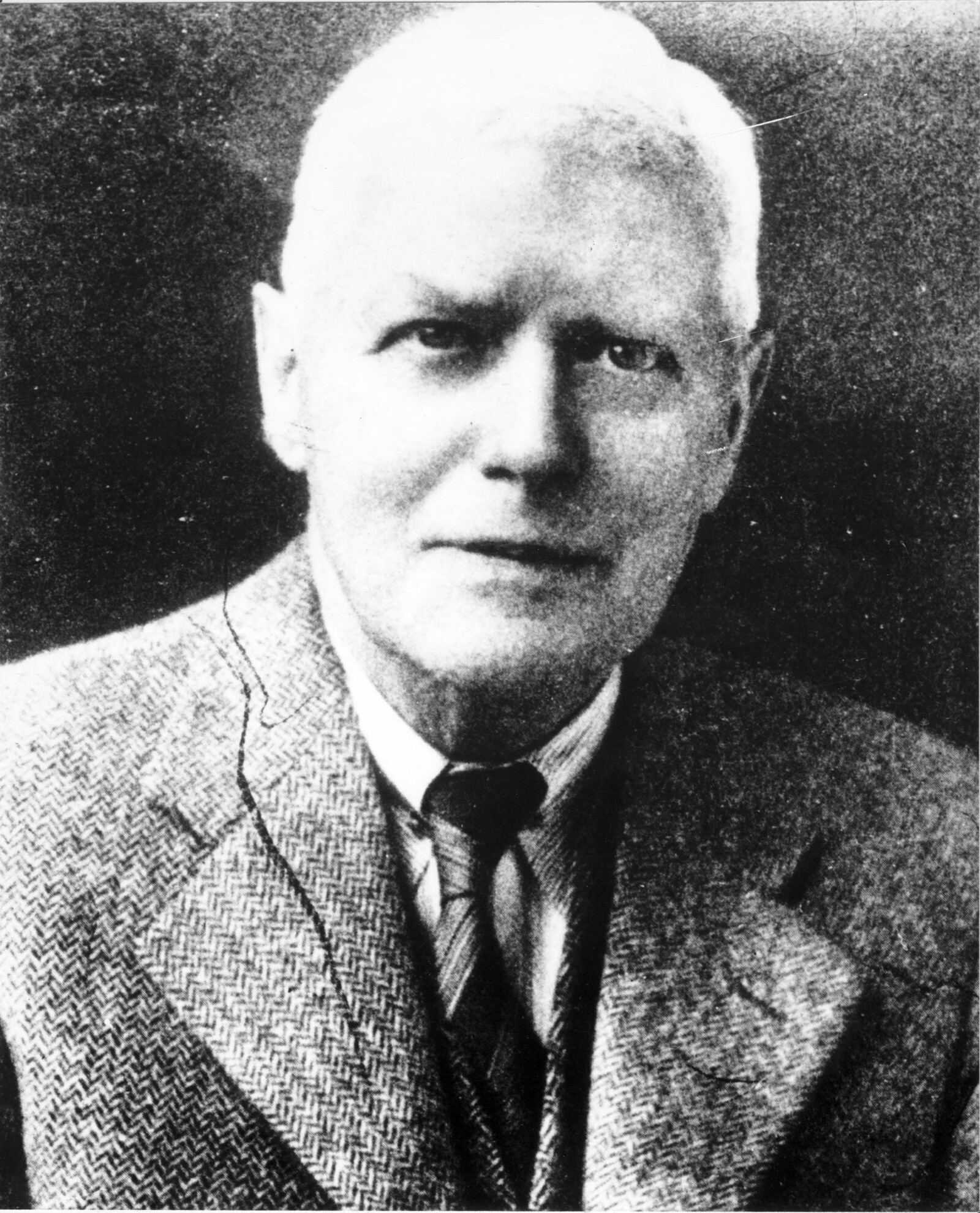

John Read le Brockton Tomlin (1864-1954)

One letter remains to me, a volunteer helping to record the archive, particularly poignant. The letter in question was written by Professor Dr. Phil Franz Alfred Schilder, a malacologist from Naumburg in Germany.

Schilder wrote the letter to Tomlin on July 11th, 1946. Within this letter, Schilder describes his anxieties surrounding his German heritage in a post-WW2 world, fearing ‘whether any Englishman ever will take notice of any German’ again, because of his nation’s ‘unbelievable barbarism’. Schilder further shares his assumption that Tomlin had been killed in the German bombings of the English South East Coast and Hastings, before it was revealed that the destruction of the English Coast had been falsely exaggerated by Nazi Germany’s official records. This helps us to understand a little more about what life was like for German citizens living in Nazi Germany during the War; Schilder felt very much a victim of Hitlerism, not just through being lied to by figures of authority, but a victim too in the tense and intolerant political and social climate Hitler created in Nazi Germany. Schilder, having a half-Jewish wife, describes their suffering under the Gestapo, living a constant struggle to prevent his wife from being taken to a concentration camp, and being treated himself as a ‘“suspicious subject”’ in Germany.

Schilder describes how he lost his job, Assistant Director of a Biological Institute, for ‘political reasons’ in 1942, and that he only regained his position once the War had ended. Once appointed Professor of Zoology at the University of Halle in November 1945, he delivered a course of lectures, but Schilder reveals how, in the bombings of Germany during the conflict, he lost all of his property. He also describes how his statistical paper on the development of Prosobranch Gastropods during geological times, was ‘destroyed by bomb shells at Frankfurt’. Losing all of his research and property seems, to Schilder, the end of Tomlin’s and his relationship: ‘I can hardly think to see you once more’, and he regretfully states he is sorry to be cut off from a country he spent many ‘fine holidays’ with ‘noble-minded scientific friends’ in.

Schilder can be seen sat on the left in this photograph, also part of the Tomlin Archive collection. ‘June 1932, on downs near Falmer’

This letter’s tone is overwhelmingly one of pain and loss. The Second World War was a truly catastrophic event that claimed millions of lives, and in this letter we are able to understand how the conflict ripped apart the lives of survivors too. It destroyed Schilder’s livelihood, years of pain-staking work, his career, and even many friendships he once had. This letter may first and foremost provide an insight into Schilder’s life, but it also tells us so much more about the unforgiving and intolerant social climate created by Hitler which still exists, in part, to this day, the vast number of victims that were affected, and the sheer scale of destruction and loss it had on so many lives.

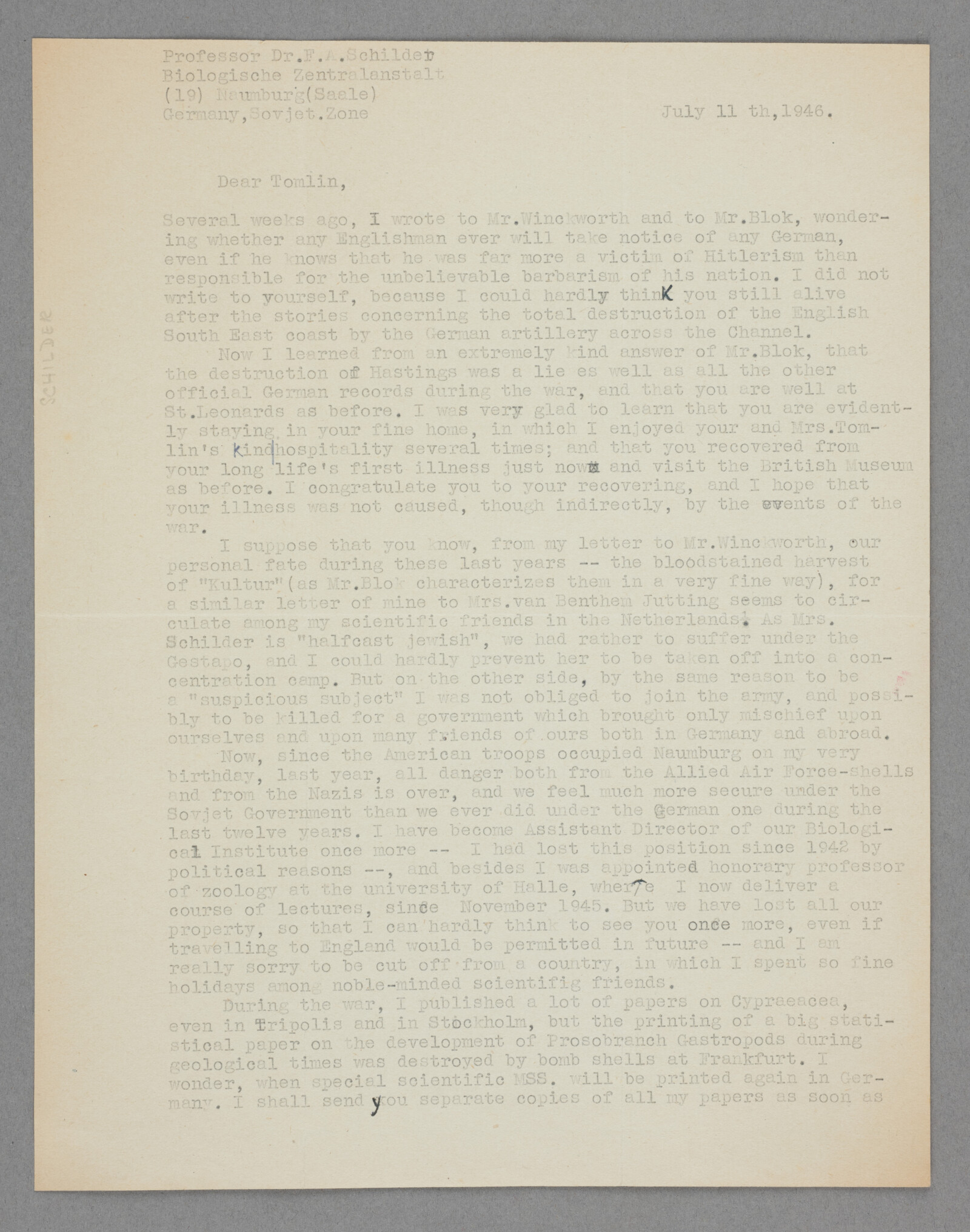

Transcription of the letter dicussed from F. A. Schilder to J. R. le B. Tomlin:

Naumburg, Germany

July 11 th, 1946.

Dear Tomlin,

Several weeks ago, I wrote to Mr. Winckworth and to Mr. Blok, wondering whether any Englishman ever will take notice of any German, even if he knows that he was far more a victim of Hitlerism than responsible for the unbelievable barbarism of his nation. I did not write to yourself, because I could hardly think you still alive after the stories concerning the total destruction of the English South East coast by the German artillery across the Channel.

Now I learned from an extremely kind answer of Mr. Blok, that the destruction of Hastings was a lie as well as all the other official German records during the war, and that you are well at St. Leonards as before. I was very glad to learn that you are evidently staying in your fine home, in which I enjoyed your and Mrs Tomlin’s kind hospitality several times; and that you recovered from your long life’s first illness just now and visit the British Museum as before. I congratulate you to your recovering, and hope that your illness was not caused, though indirectly, by the events of the war.

I suppose that you know, from my letter to Mr. Winckworth, our personal fate during these last years - - the bloodstained harvest of “Kultur” (as Mr. Blok characterizes them in a very fine way), for a similar letter of mine to Mrs. van Benthem Jutting seems to circulate among my scientific friends in the Netherlands. As Mrs. Schilder is “halfcast jewish”, we had rather to suffer under the Gestapo, and I could hardly prevent her to be taken off into a concentration camp. But on the other side, by the same reason to be a “suspicious subject” I was not obliged to join the army, and possibly to be killed for a government which brought only mischief upon ourselves and upon many friends of ours both in Germany and abroad.

Now, since the American troops occupied Naumburg on my very birthday, last year, all danger both from the Allied Air Force-shells and from the Nazis is over, and we feel much more secure under the Soviet Government than we ever did under the German one during the last twelve years. I have become Assistant Director of our Biological Institute once more - - I had lost this position since 1942 by political reasons - -, and besides I was appointed honorary professor of zoology at the university of Halle, where I now deliver a course of lectures, since November 1945. But we have lost all our property, so that I can hardly think to see you once more, even if travelling to England would be permitted in future - - and I am really sorry to be cut off from a country, in which I spent so fine holidays among noble-minded scientific friends.

During the war, I published a lot of papers on Cypraeacea, even in Tripolis and in Stockholm, but the printing of a big statistical paper on the development of Prosobranch Gastropods during geological times was destroyed by bomb shells at Frankfurt. I wonder, when special scientific MSS. Will be printed again in Germany. I shall send you separate copies of all my papers as soon as such mails will be allowed.

I should be very glad to learn from yourself that you escaped the greatest catastrophe of the white race, and that you recovered fully from your recent illness.

Please tell my kind regards to Mrs. Tomlin.

Yours sincerely

F. A. Schilder