Return of the Vikings? Week One

, 29 August 2012

RETURN TO LLANBEDRGOCH (WEEK ONE)

The unexpected discovery in 2001 of an intramural burial within the early medieval enclosed settlement at Llanbedrgoch raised a new series of questions about the site, its occupants, their activities and their relationships with other regions.

We returned to the site a week ago, and the last eight days have focused on setting out the new areas of excavation, removing ploughsoil, monitoring weather forecasts and adjusting the daily tasks to make the best of at times trying conditions. The team of students includes volunteers from Bangor and Cardiff, and one from Toronto (Canada). Yesterday we were joined by some local, experienced, volunteers from Gwynedd and Anglesey. They have all been outstanding, and the early medieval archaeology of the site is already being transformed. Excavation is an ongoing process, and if you follow us over the next three weeks, the team will provide you with personal insights into the excavation.

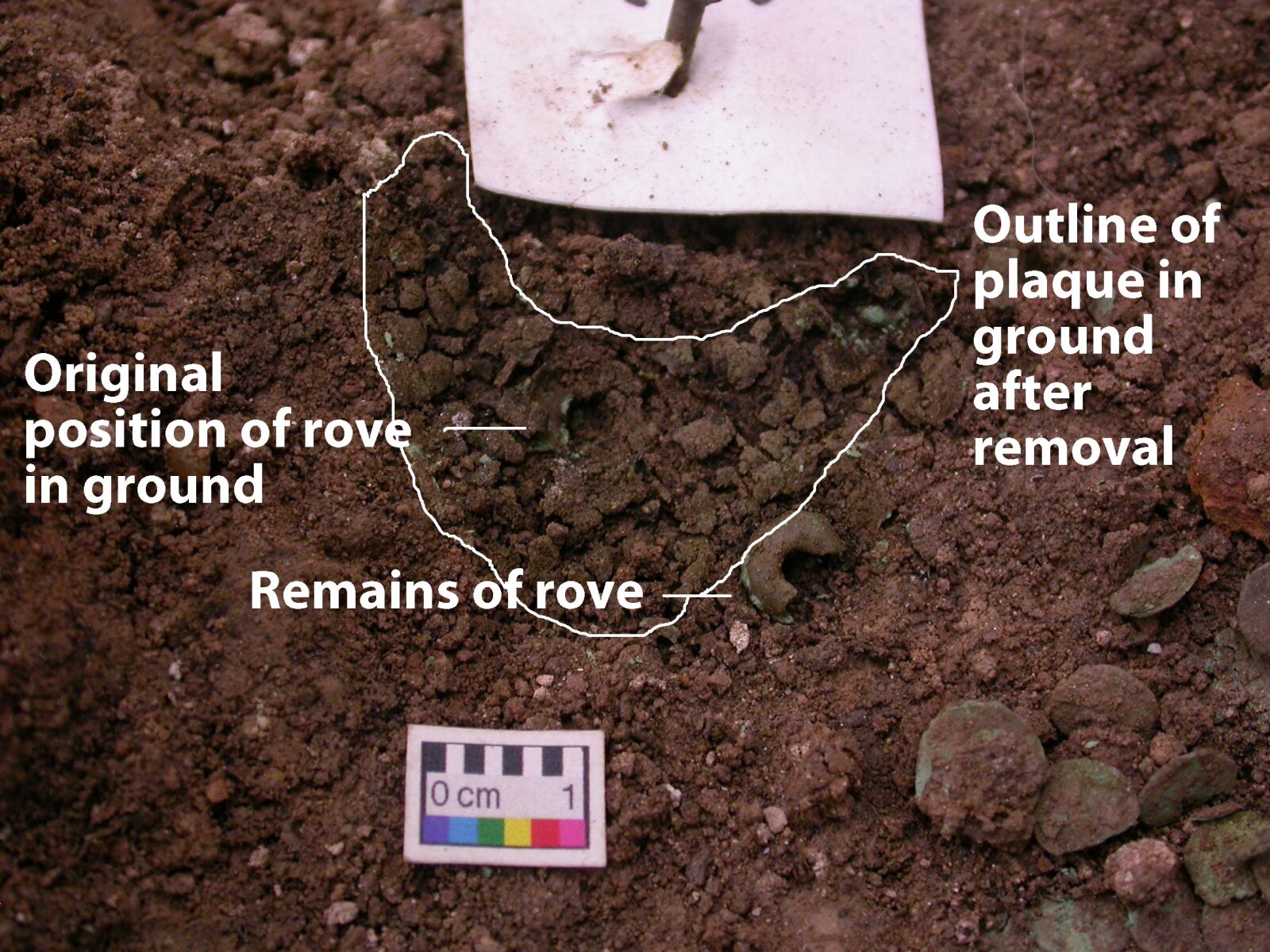

Even though the research design has clearly stated objectives, the work often reveals evidence of a completely different nature. Our return this year was in fact the result of such an unexpected discovery and its implications. The burial from inside the enclosure (Burial 6) was not revealed in plan through specific searching for inhumations, or the recognition of subtle changes in soil colour or character, but by the decision to cut a narrow trench through the early medieval ‘black earth’ midden material in the south-western area of the site in order to reveal the midden sequence and facilitate section drawing and sampling.

In spite of the profound silence of the individual in this grave and those discovered in 1998-99, they continue since their discovery to help us answer in increasing detail a range of fundamental historical questions:

How did the people of Llanbedrgoch and north-west Wales, who had contact with Anglo-Saxons, Irish and Scandinavians, respond to such peoples?

How does the archaeological evidence for the politics and economy of early medieval Wales compare to that provided by other sources?

Were the daily lives of people at Llanbedrgoch during the sixth and seventh centuries different from those in the ninth and tenth centuries?

What types of diet and health did they enjoy?

How did Christianity affect their lives and burial practices?

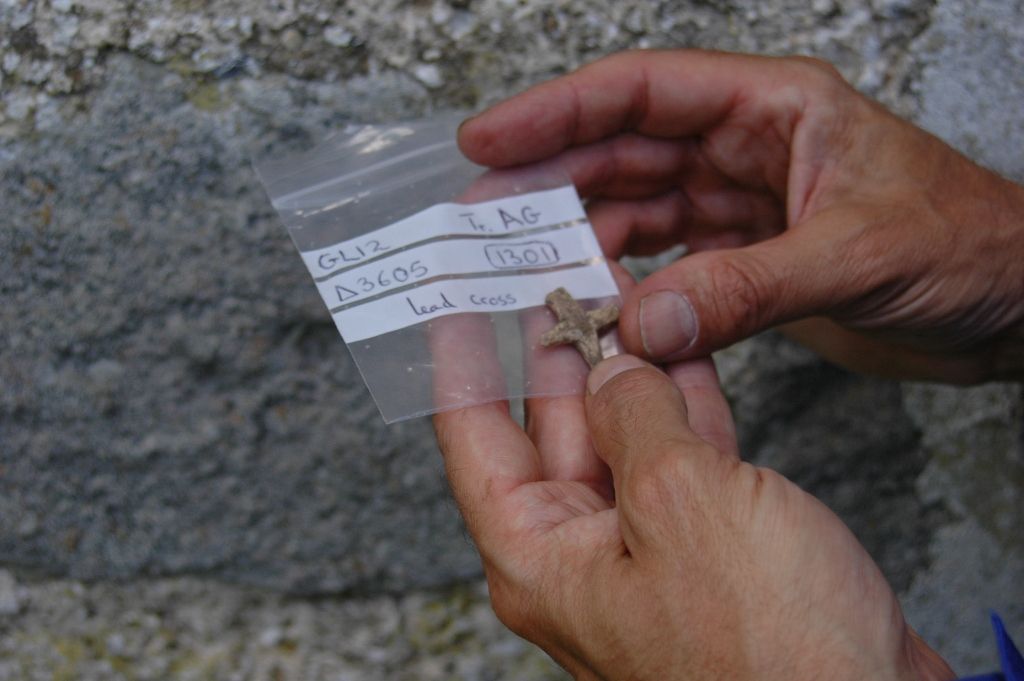

We have already begun to answer some of these questions – one of the first artefacts to be found last week in the ploughsoil was a lead necklace pendant in the form of a cross – slightly larger than one found in an earlier season of excavation at the site.

This site continues to amaze, surprise and inspire – follow us if you can.

Mark Redknap