Continued excavation and investigation of blocklifted lorica segmentata

13 October 2011

Just a short blog entry today, describing the completed excavation of another area of the soil block, and some of the interesting features that have cropped up.

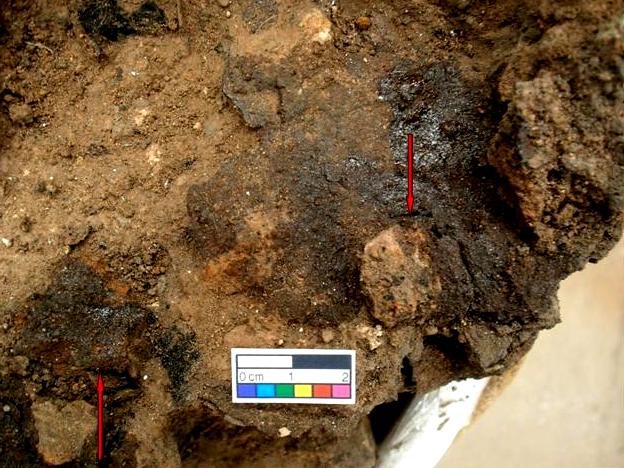

This section of the block is composed of what appears to be two flat lorica plates, one lying at a 45 degree angle to the other. Note the length of the straight edge of plate; I believe that this plate will be one of the large plates that came across the middle of the cuirass. I have included annotations indicating small areas of potential importance, such as the corroded remains of fittings (see red arrows), which stand proud to the surface of the plates. The gap between the plates, which shows how damaged and broken the edges of the lorica set really are, can be seen in the second picture.

I have found another fragment of plate with a rolled edge (see third photograph), though the roll itself is much narrower in comparison with that exposed within the girth hoop (refer to previous blog entry). The fragment itself is also a little too small to detect any curvature or to easily extrapolate a larger shape, but could this fragment be part of a plate (the breast or backplate) that would have been in contact with the wearer’s neck? All comments and opinions regarding this little hypothesis are welcome.

I have included a macro shot of a small cylindrical item: whilst this may be physically unimpressive, I believe that this could be the iron pin that would have been drawn through a lobate hinge, holding the shoulder plates together.

As mentioned above, obvious fittings that are immediately identifiable still haven’t been found, and careful excavation has only managed to produce vague shapes of what is essentially metal corrosion. I have included in the last photograph a view of an area of probable lorica attachments and fittings, though only a very good quality x-ray will be able to make any sense of these lumpy features.

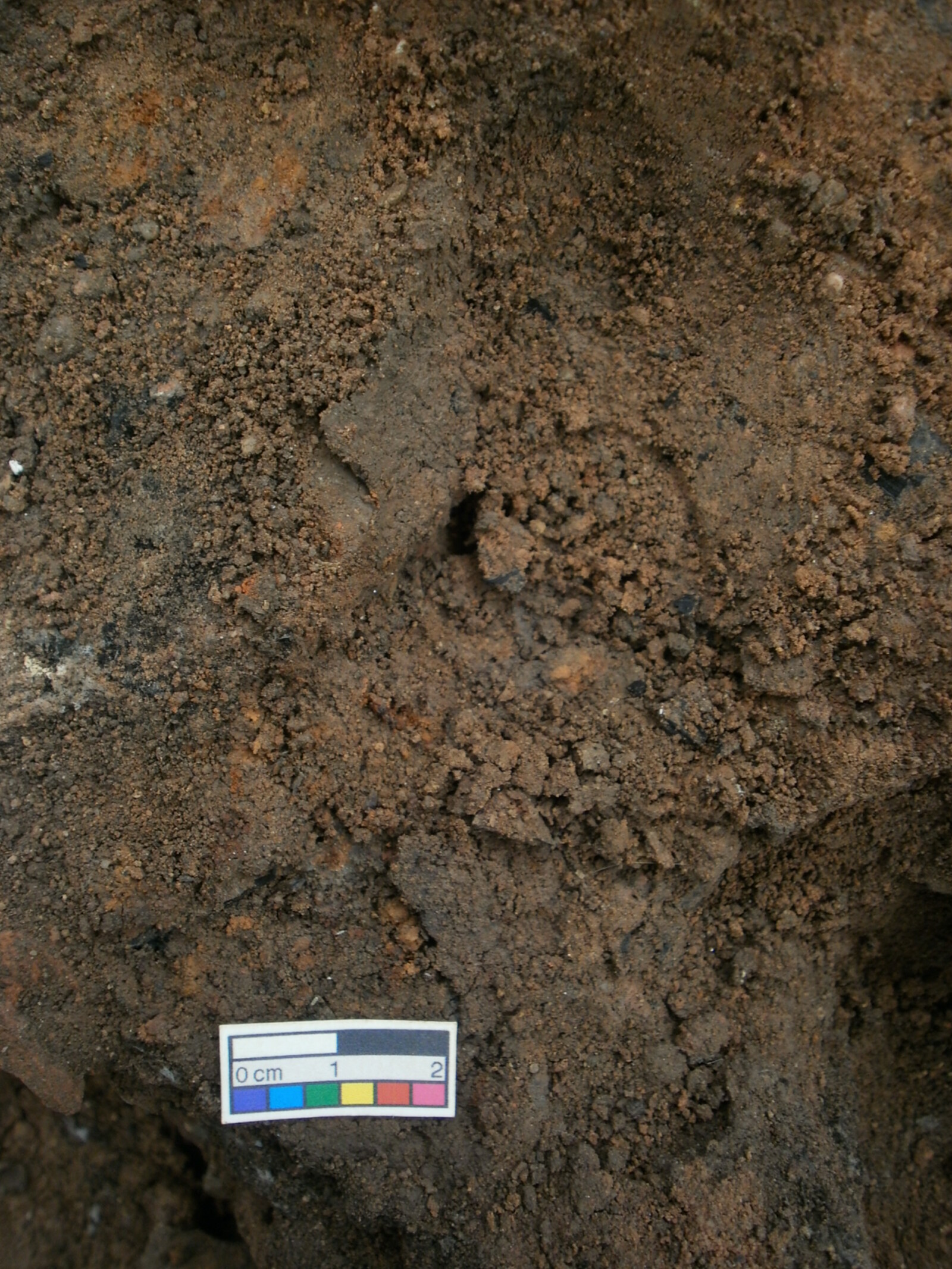

As a last aside, I thought I should provide a brief explanation for the condition of the buried lorica segmentata. Readers may have noticed how exposed finds lack the thick crusts of rust and voluminous corrosion products typical of a lot of archaeological iron objects: this is most likely because the thin iron plates corroded extremely quickly, with the iron leeching into the soil. Whilst this does mean that I will not have to spend hours removing powdery iron corrosion in order to reach a more certain surface on the iron, it also indicates that the remaining ‘object’ is more of a pseudomorph lying on top of the soil: this is why the ‘plate’ most often does not respond to the pull of a magnet. This level of deterioration will have implications for the eventual conservation treatment of the armour, as I may be unable to extract the iron plates (which have very little physical integrity), from the soil.