Seaweeds in Northumberland

, 5 March 2015

On 19th February, I joined science curator Kate Mortimer-Jones to study marine life on the shores around Berwick-upon-Tweed in Northumberland, not far from the border with Scotland. While Kate hunted for magalonid marine bristleworms, I looked at seaweeds. Much of England’s east coast is not particularly suitable for seaweeds; however, the rocky shores around Northumberland form plenty of ideal habitats.

It was early in the year, so I wasn’t expecting to see the seaweeds that die down for the winter (similar to annual and perennial flowering plants). I was also expecting a lower diversity here when compared with Welsh shores due to the colder climate. Species with south-western distributions that prefer a relatively warmer climate, such as Brown Tuning Fork Weed (Bifurcaria bifurcata), relatively common in Wales, do not grow as far north and east as Northumberland. With climate change, however, there is always the possibility that these southern species may expand their range further north. This is more likely for non-native species that are in the process of establishing in the UK, so I was on the look-out.

There are some seaweeds that only grow in the north of the UK, such as the Northern Tooth Weed (Odonthalia dentata) which is absent from Wales. I wanted to become familiar with these in the field rather than just seeing them as pressed specimens in our collections. It’s always exciting to find a species for the first time in the wild too.

Despite the time of year and the north-eastern location, the very sheltered shore was an excellent one for seaweeds and I documented a wide range of species. While it was important to collect specimens as a permanent back-up for records and for future research, I had to remind myself not to collect too many as they take a long time to process and I didn’t want to be up until the ‘wee hours’.

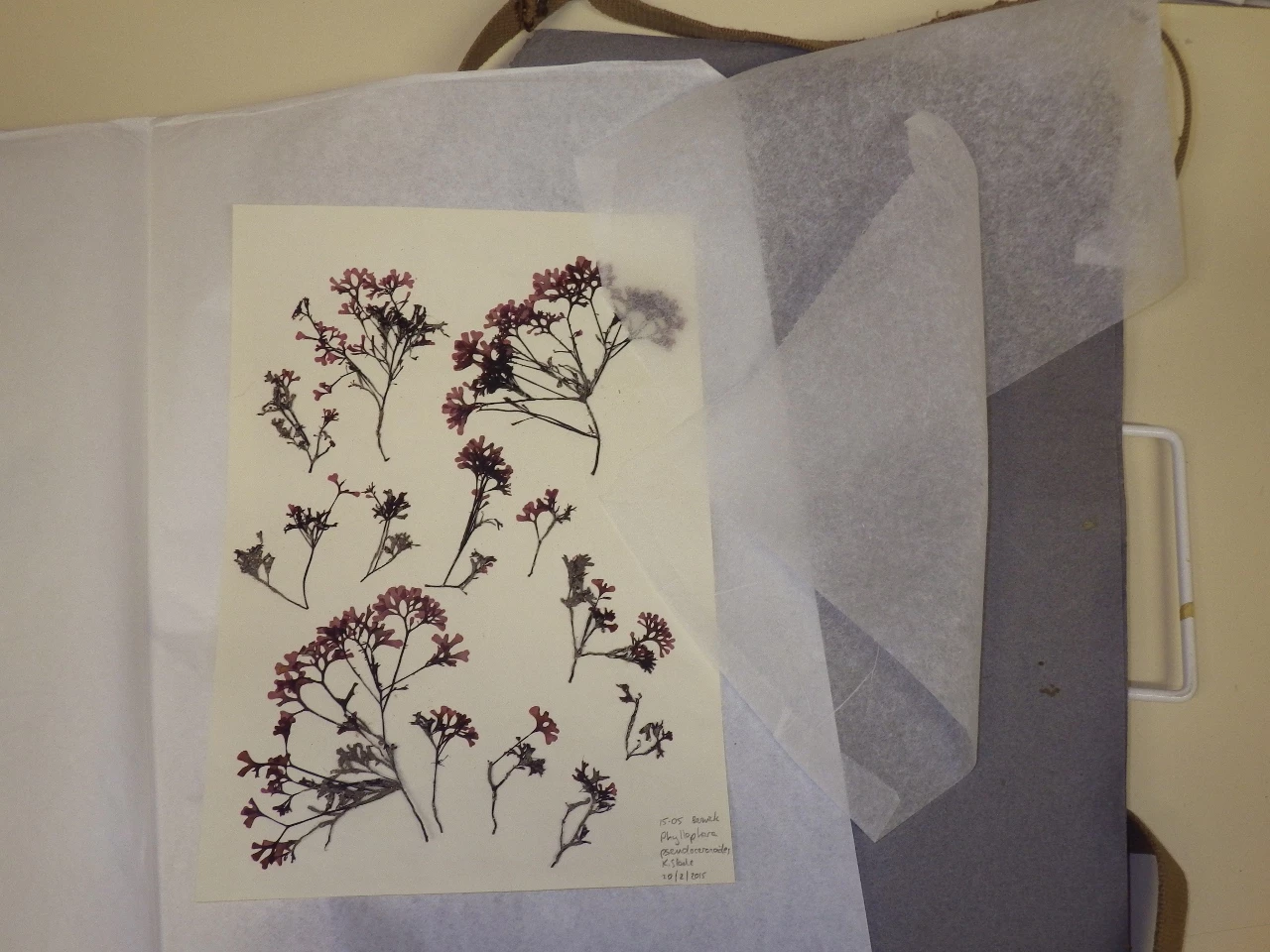

Preservation of the seaweeds involves several techniques depending on future use. To preserve the seaweed’s DNA for molecular analysis, the seaweed needs to be dried as quickly as possible in a bag with silica gel. Combining DNA characters with morphological ones (such as shape and colour) is sometimes the only way to be sure of an identification. To preserve 3D structure and some microscopic details well, a sample is placed in a tube with formaldehyde for fixation. Finally, the traditional and still most effective method for overall preservation is to press and dry the specimen, unfortunately this is the most time consuming process. You float each seaweed out onto paper, place nappy liners on top (a crucial part to stop the seaweed sticking to the paper above it), then place a piece of blotting paper underneath and on top and put it into a plant press. At least once a day, I swapped the wet blotting paper for dry and made sure the wet paper dried out quickly enough to be used in the next cycle. A lengthy procedure, but worth it for excellently preserved specimens that will be invaluable for future research.

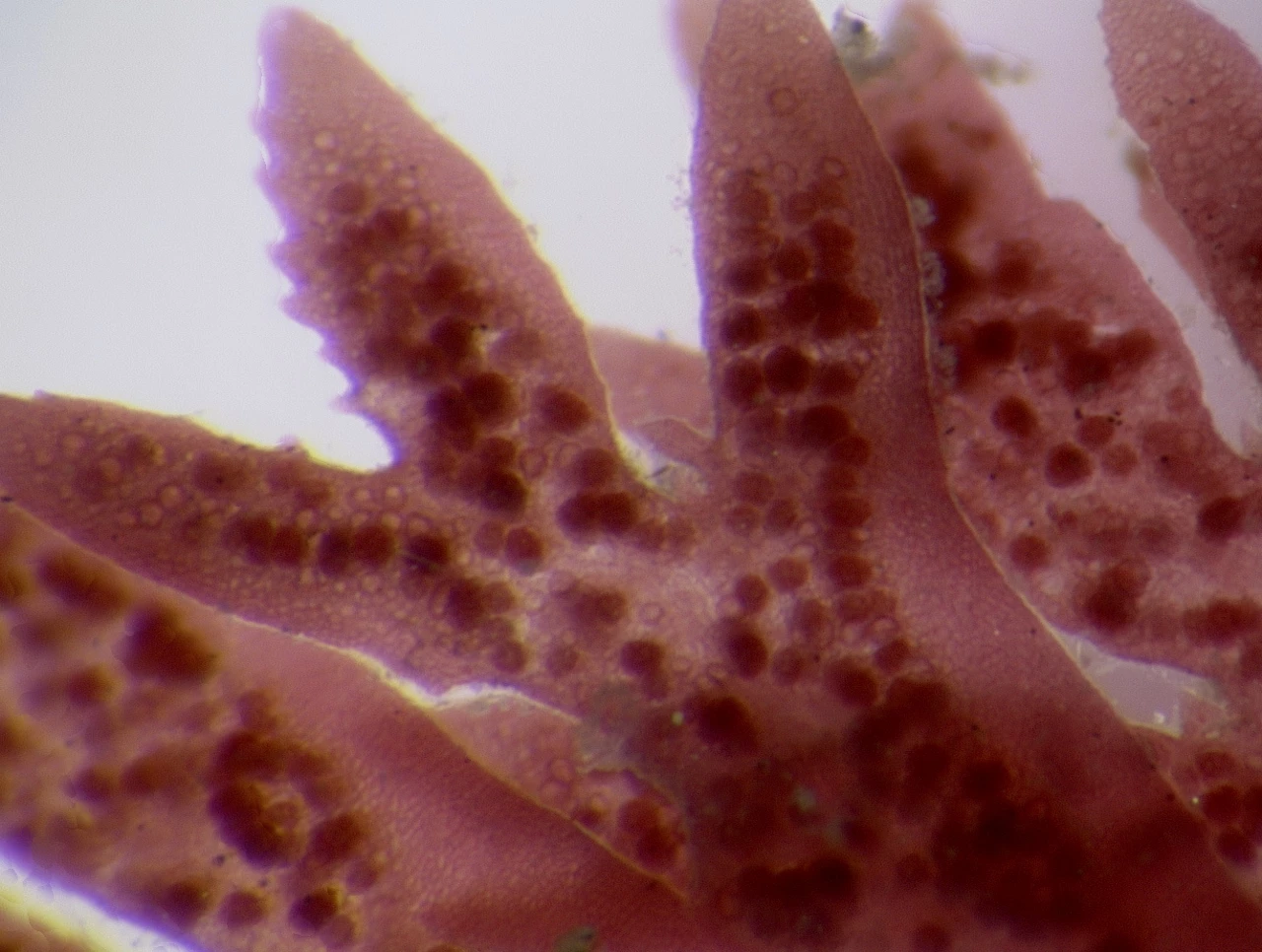

I had access to a microscope with a camera attached and so was able to take close-up images of the seaweeds while they were fresh. These will be useful when looking at dried specimens back in the museum. Characters such as colour and 3D structure can be altered in the drying process, but will show up well in these photos. I also took lots of photos with a waterproof camera (it is too terrifying to take a non-waterproof camera onto the shore!) and I will share some more of these in my next blog.