United Nations international year of the periodic table of chemical elements: April - calcium

, 30 April 2019

Continuing the international year of the periodic table of chemical elements, for April we have selected Calcium. Known by most as the fundamental element in bone-forming or limestone, it has a host of other applications and is present in seabeds and marine life past and present.

Calcium (Ca) is a light-coloured metallic element with an atomic number of 20. It is crucial for life today and commonly forms a supporting role in plants and animals. The 5th most common element in the earth’s crust, calcium forms many useful rocks and minerals such as limestone, aragonite, gypsum, dolomite, marble and chalk.

Aragonite and Calcite, the two most commonly crystalised forms of calcium carbonate, helped form the 2 million shells in our mollusc collection, the core of which is the Melvill-Tomlin collection, donated to the museum in the 1950s. An international collection it contains many rare, beautiful and scientifically important specimens and is utilised by worldwide scientists for their research. Pearls, also made of aragonite and calcite, are produced by bivalves such as oysters, freshwater mussels and even giant clams. In nature pearls are the result of the molluscs’ reaction against a parasitic intruder or a piece of grit. The mantle around the soft bodied animal secretes calcium carbonate and conchiolin that surrounds the invading body and imitates its shape so they are not all perfectly spherical. In the pearl industry the oyster or mussel is ‘seeded’ with a tiny orbs of shell to ensure that the resulted pearl is totally spherical.

Mollusc shells are created as protective shields by their soft-bodied owners and this is true of other invertebrates, especially in the world’s oceans. Coral reefs and some marine bristle worm tubes (Serpulidae, Spirorbinae) rely on the reinforcing nature of calcium carbonate to provide support and protection to their soft bodies. Crustaceans such as crabs and lobsters have a hard exoskeleton strengthened with both calcium carbonate and calcium phosphate. Calcium required after moulting in lobsters, crawfish, crayfish and some land crabs is provided by gastroliths (sometimes referred to as gizzard stones, stomach stones or crab’s eyes). They are found on either side of the stomach and provide calcium for essential parts of the cuticle such as mouthparts and legs. The museum’s collections holds nearly 750,000 marine invertebrates, including crustaceans, corals and bristleworms.

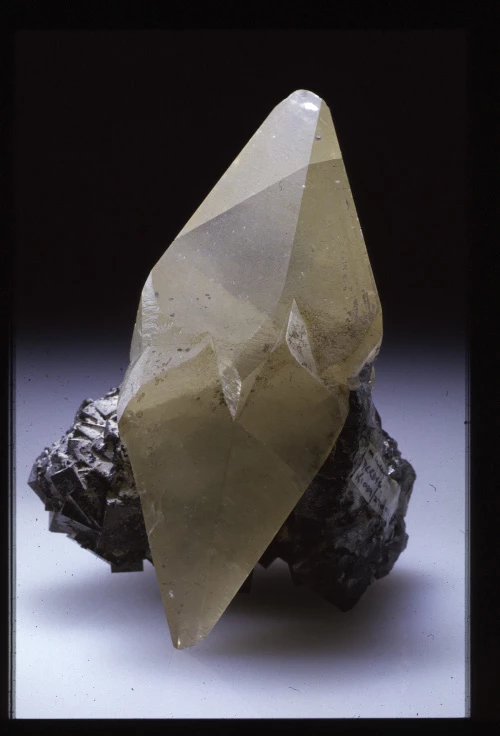

Many of the 700,000 fossils in the Museum’s collections are also made of calcium minerals. Invertebrates use two main forms of calcium carbonate to make their shells and exoskeletons, and the one they use influences how likely they are to be immortalised as fossils. Aragonite, found in the shells of molluscs such as ammonites, gastropods and bivalves, is unstable and doesn’t usually survive for millions of years. During fossilisation, aragonite shells either dissolve away completely, or the aragonite recrystallizes to form calcite. Calcite was used to make the shells and skeletons of extinct groups of corals, articulate brachiopods, bryozoans, echinoderms and most trilobites. It is much more stable than aragonite, so the original hard parts of these creatures are commonly found as fossils, millions of years after they sank to the sea floor. Large calcite crystals are often found filling spaces in fossils, such as the chambers inside ammonite shells. Vertebrates use a different calcium mineral to make their bones and teeth: apatite (calcium phosphate), which can survive for millions of years to make iconic fossils such as dinosaur skeletons and mammoth tusks.

The Museum’s rock collections contain many limestones, rocks formed at the bottom of ancient seas from bits of shells and other calcium carbonate-rich remains. For millenia, people have used limestones as a construction material: from carved stone in the iconic Greek and Roman temples; broken fragments as ballast in the base layer of railways and roads; or burnt to form lime in the manufacturing of cement. National Museum Cardiff and other iconic buildings in Cardiff Civic Centre were built from a famous Dorset limestone called Portland Stone. The Museum’s floor is tiled with marble, limestone that has been transformed (‘metamorphosed’) under great heat and pressure. Marble has long been prized by sculptors, since the ancient Greeks and Romans. The Museum’s art collections include works in this material by Auguste Rodin, John Gibson, Sir Francis Chantrey, Sir William Goscombe John, and many others. There are also important examples of work by twentieth-century sculptors, such as Jacob Epstein, Eric Gill and Henri Gaudier-Breszka. They preferred carving the softer texture and density of the softer limestone, Portland Stone and sandstone.