The Abergavenny Eisteddfod

The provincial eisteddfodau came to an end at Cardiff in 1834 but a new movement, under the auspices of a new society, began another memorable journey in 1835, one which lasted until 1851. I'm referring to the eisteddfodau of Cymreigyddion Y Fenni. The remarkable woman who sponsored those eisteddfodau was of course Lady Llanover, the famous Gwenynen Gwent. She had already played her part in the provincial eisteddfodau, and had sponsored Maria Jane Williams, collator of the melodies in Ancient National Airs of Gwent and Morgannwg. She had also sponsored the famous Thomas Stephens, who won a fabulous prize, the Prince of Wales's Prize, for the volume we now know as The Literature of the Cymry, a particularly influential book in its time. Lady Llanover had also ventured inside the druidic circle, where she had been given the bardic name Gwenynen Gwent.

Although she was an Englishwoman born and bred, she turned out to be a very fiery Welshwoman. I don't believe that she ever mastered Welsh, either oral or written, yet there is no doubt at all of her loyalty and attachment to the culture of Wales. Of course she had the support of her husband, Sir Benjamin Hall, and assistance from the Reverend Thomas Price, Carnhuanawc, and Tegid, who won a handsome cup in Cardiff in 1834.

It was with the help of people such as these that Lady Llanover and her husband created a series of ten eisteddfodau at Abergavenny. They were quite, quite remarkable, and nothing else of that kind has really been seen in the Eisteddfod's history since then. They were not poor eisteddfodau by any means; they offered very substantial prizes, sometimes as much as eighty guineas. Back in the 1840s prizes such as these could be won for essays on Celtic philology, and attracted some of the greatest European Celtic scholars - people such as Karl Meyer and Albert Schultz of Germany.

Promoting Welsh Culture

The Abergavenny eisteddfodau were extremely colourful. A special hall was erected in Abergavenny to stage them because they were so popular. They were promotional eisteddfodau: at Abergavenny, Welsh culture was very much on display. They even drew attention to the local woollen industry. When Gwenynen Gwent went on her travels to Europe, she took samples of Abergavenny flannel with her, to promote them in the great houses, and even the courts, of Europe. And she never missed a chance, of course, to convince people that the folk culture of Wales was very special.

She kept harpists and had parties of dancers at Llanover Hall. And although the English language played a prominent part in those eisteddfodau too - well, how could it not? Because Lady Llanover mixed with the upper echelons of society, and managed to persuade them to give those generous prizes; you'd expect that the English language would play quite a prominent role. Then on the other hand, you had a wonderful old hero like Thomas Price, Carnhuanawc, a man who fought so strongly against the lies peddled in the Blue Books, for example. You had a man like this who was very faithful in his attachment to Welsh-language culture, and there's no doubt at all that the ten eisteddfodau held under the auspices of Cymreigyddion Y Fenni formed one of the most brilliant chapters in the Eisteddfod's history.

Lady Llanover and the Triple Harp

Lady Llanover had fallen head over heels in love, above all, with the triple harp and the folk airs and folk dances of Wales, and there's no doubt at all that the Abergavenny Eisteddfodau between 1835 and 1853 played a very important part in safeguarding those elements in Welsh-language culture. It's quite certain that the triple harp would have completely disappeared from Wales were it not for Lady Llanover, who employed a harpist in Cardiff, Bassett Jones, to make harps. That is, she set competitions in the eisteddfodau for triple harp players, and instead of giving them money as prizes, she'd give them a new harp. It seems that this Bassett Jones in Cardiff made around three dozen brand-new harps, which reached every part of Wales. And Lady Llanover remained fervently in favour of what she considered to be Welsh traditional culture, right up until the year of her death in 1896. She was called a 'very fiery Welshwoman' by one of her acquaintance, although she was in fact an Englishwoman by ancestry and birth. Thank Heaven for people of her kind.

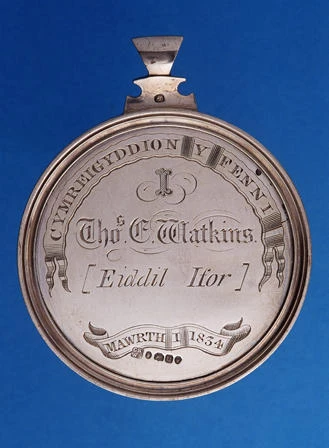

Abergavenny, 1834: Eiddil Ifor's medal

In the Museum at St Fagans there's a very good collection of medals and other prizes won in the eisteddfodau of Cymreigyddion Y Fenni. Here are just three of them. This is one from the year 1834, a medal won by a man who called himself Eiddil Ifor, an essayist who competed quite regularly in the eisteddfodau. The Abergavenny eisteddfodau, as you might expect, gave some prominence to essays on subjects associated with Welsh history, both local history such as that of Abergavenny and the area, and of course Welsh history in a broader sense. Eiddil Ifor competed regularly and there are probably a good half-dozen of the fine medals he won here in the Museum.

Abergavenny 1837: a medal for playing the triple harp

This is another medal, from the year 1837, which was won by a harpist, William Morgan. It's hardly surprising that we're showing one of these medals, because Lady Llanover believed one hundred per cent that the triple harp was the national instrument of the Welsh people. She detested the pedal or concert harp, and detested the piano even more. That, of course, is why she tried to create as many new triple harps as she could. This medal, won by William Morgan, is a reminder of that essential fact. If it hadn't been for Lady Llanover and then, at the beginning of the twentieth century, the advent of someone like, say, the famous Nansi Richards, we might have lost the triple harp. That would have been a very great loss indeed.

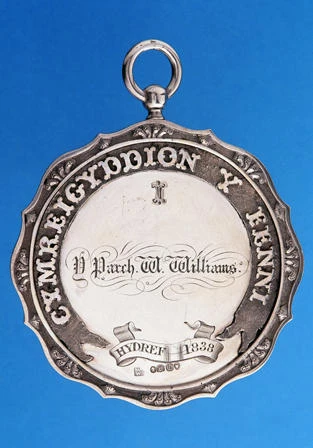

Abergavenny, 1838: the elegy for Gomer

Here's another medal from the year 1838, and here he is once again, William Williams, Caledfryn, a man who made his mark in Beaumaris some six years previously with his awdl on the shipwreck of the Rothesay Castle. Here in 1838 he composed an elegy to the famous Joseph Harris, Gomer, the man who founded the paper which led of course to the famous periodical, Seren Gomer, one of the first magazines to report on the eisteddfodau in Wales. Caledfryn wrote in memory of Gomer and his son, the famous Ieuan Ddu, who died at a tragically young age, and who, it had been predicted, would have become a star on the Welsh cultural scene.

Promoting Welsh Industry

The Abergavenny eisteddfodau are so interesting. Other medals in the collection show how the woollen industry was being promoted, how attention was drawn, even, to industrial south Wales, where the iron works and the coal pits were, of course, drawing more and more people into the area. Take that, together with the eisteddfodau's appeal to the bigwigs, and to those Celtic scholars who were willing to come over to Abergavenny from Germany, and you'll see what an exciting period the Abergavenny chapter is in the history of the Eisteddfod.