Tom Sharpe's Antarctic Diary 2011-12-22

, 22 December 2011

Monday 21 November

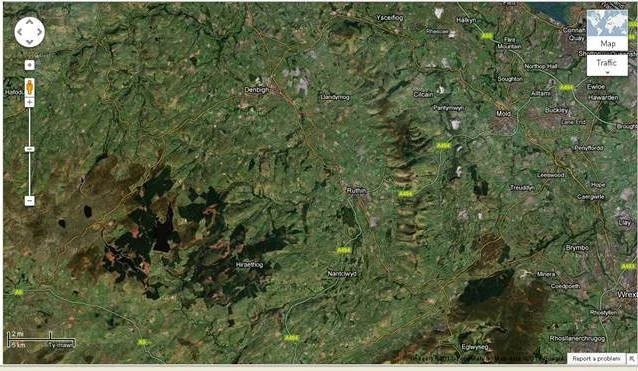

We've continued to push south, although by a rather round about route to avoid the thickest pack ice, and passed 77o south latitude.

On the western horizon we had an incredible view of the Victoria Land coast of mainland Antarctica and the Transantarctic Mountains. To the south we could see Ross Island and Mount Erebus, the most southerly active volcano on earth.

We eventually broke through into a large area of open water as we entered McMurdo Sound. As we sailed along the west coast of Ross Island, we headed for a small bay at Cape Royds and ran the ship up onto the fast ice - thick sea ice attached to the land. From there it was a short helicopter ride ashore.

A walk of a few hundred metres took us to a sheltered little cove where, protected from the winds by a ridge of glacial moraine, there stood a small wooden building. This was the base hut of Ernest Shackleton's Nimrod Expedition of 1907-1909. A major conservation project by the New Zealand Antarctic Heritage Trust has recently completed work on the hut and its contents, and they've done a magnificent job. Tins of food are still stacked on the shelves, sledges rest on the rafters, clothing and sleeping bags lie on the beds, and crates of supplies are piled against the outside wall. To stand in this hut is awe inspiring.

On this expedition, Shackleton pioneered a route which Scott would later follow through the Transantarctic Mountains, and got within 97 nautical miles of the South Pole. Although he knew he could be the first to reach the South Pole, he turned back. He realised that if they continued they would not have enough food to make it back alive.

Shackleton took several scientists with him, one of whom was a St Fagan's born geologist, T.W. Edgeworth David, then Professor of Geology in Sydney. Based at this hut, David led the first ascent of Mount Erebus, 3795 metres high, and also led another team on a long sledging journey up onto the Polar Plateau to reach the South Magnetic Pole.

We had time to see the hut and take a walk to the most southerly penguin colony in the world, on the coast around Shackleton's hut. The Adelie penguins here provided an extra source of food for the expedition.

Instead of flying back to the ship, I opted to hike back across the fast ice to retrieve some marker flags we had laid out as a walking route in case the weather turned. This is perfectly safe as long as you keep a look out for tide cracks - fissures in the ice caused by tidal movement.

Their dangers were demonstrated when my hiking companion immediately fell into one. Luckily he went down only a couple of feet. It was just as well, as he had the rescue line.

.webp)