E-volunteer guest blog

, 2 September 2021

Winter 2020. Nearly a year into the pandemic which rocked everyone's life. In the middle of a second raft of restrictions – all normal activities, group meetings, trips to see family, shopping even, put on hold for an indeterminate time – life was stagnating somewhat.

One of the many wonderful things about living in this part of Wales – as well as the space, the quiet, the beauty (with a view of the Preseli Hills), learning Welsh and interacting with the Welsh community – was the National Wool Museum, only a few miles down the road. With added leisure time now I was retired, I could indulge my obsession with all things sheep and wool-related. I became a craft volunteer at the museum, meeting with a group of spinners every week to spin, learning new things, meeting the wide range of visitors and joining in museum events. The museum and cafe staff were always friendly and welcoming, willing to indulge and encourage my attempts at Welsh. It felt like a second home. The pandemic put an end to that.

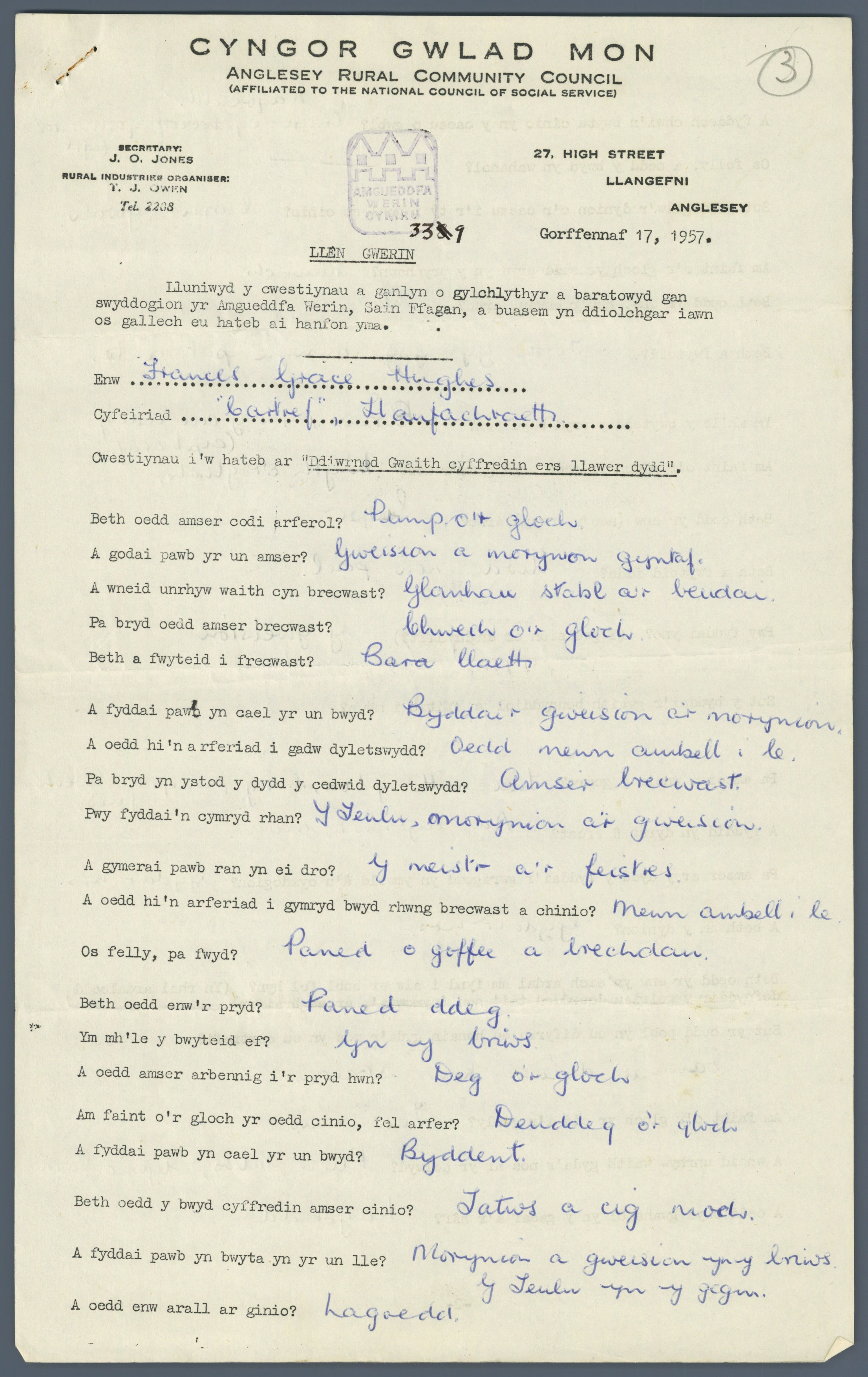

How exciting it was, then, when I saw the museum adverting for volunteers to transcribe answers to questionnaires, some filled out fifty years ago. I consider myself privileged to have been accepted to join the 'team'. Transcribing from handwritten documents – in Welsh- has been quite a challenge, but an enjoyable one. My dictionary and Google Translate have helped me check if what I am transcribing makes sense and there is a great sense of achievement when a seemingly unreadable word suddenly fits the sentence. I am learning many words that Welsh speakers may or may not know but are new to me. Do people here still know the meaning of 'sucan'? Whilst its English equivalent, given as 'gruel', conjures up the privations of poor orphans such as Oliver Twist, the Welsh sucan appears to have been somewhat of a treat at harvest time. I haven't found anyone around here yet who has heard of a room called a 'rhwmbwrdd' (is it a dining room?)

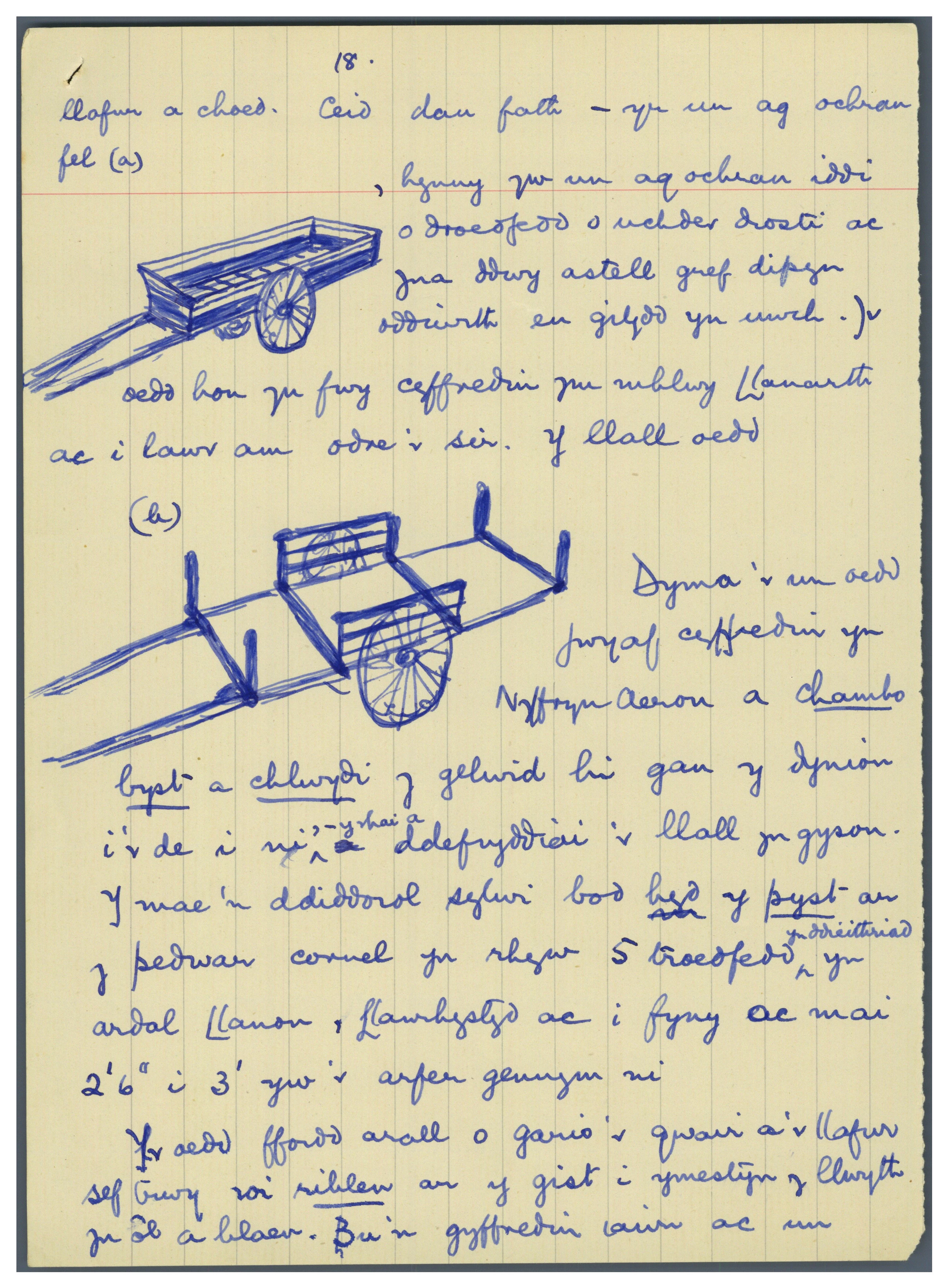

Many documents reply in a basic manner to questions about daily meals and work routines, with a noticeable lack of variation in diet (mostly 'cawl', a broth kept on the go, added to and reheated for several days' meals) and basics such as family clothing paid for by selling hand-knitted socks or eggs, but some have more detail. I am learning about which wood is most suitable for different parts of a cart (ash for the axle, oak for the wheel spokes), how neighbours helped each other with workload rather than giving presents and other customs that have died out or changed since the early 20th century. I have spoke to local people, some of whom know nothing of 'Calennig', and others who explain it as a custom for children akin to Halloween, but at the turn of the century (in the Preseli area at least) it was the old women, widowed or unmarried, who went round the village collecting small presents of money at New Year. Is there anyone now who knows that children would roam the fields in early spring trying to get a sight of the first lamb, called 'Dafad Las' (blue sheep) for which they would be rewarded with the sum of three pence? In the Welsh way, many people were referred to by their name followed by the name of their house or farm, which means it is possible to locate the properties mentioned by an internet search. It is interesting to note that several of these houses are now pictured as ruins or are listed as holiday accommodation.

It has been – it is – a lovely way to stay connected to Wales, past and present, as well as helping with my Welsh learning and giving me a chance to contribute to the work of the museum and preserve Welsh memories.