Diatom diversity of the Falkland Islands

, 31 May 2016

Since 2011 Museum scientists have been part of an international team helping to fill the gap in our knowledge of the diversity of Lower Plants (mosses, fungi and algae) in the Falkland Islands. To date, work has been principally on the mosses and lichens of this environmentally sensitive British dependency. In 2015, Dr Ingrid Jüttner, Principal Curator Botany, was awarded a Shackleton Scholarship to visit the Falkland Islands to study the biodiversity of freshwater diatoms.

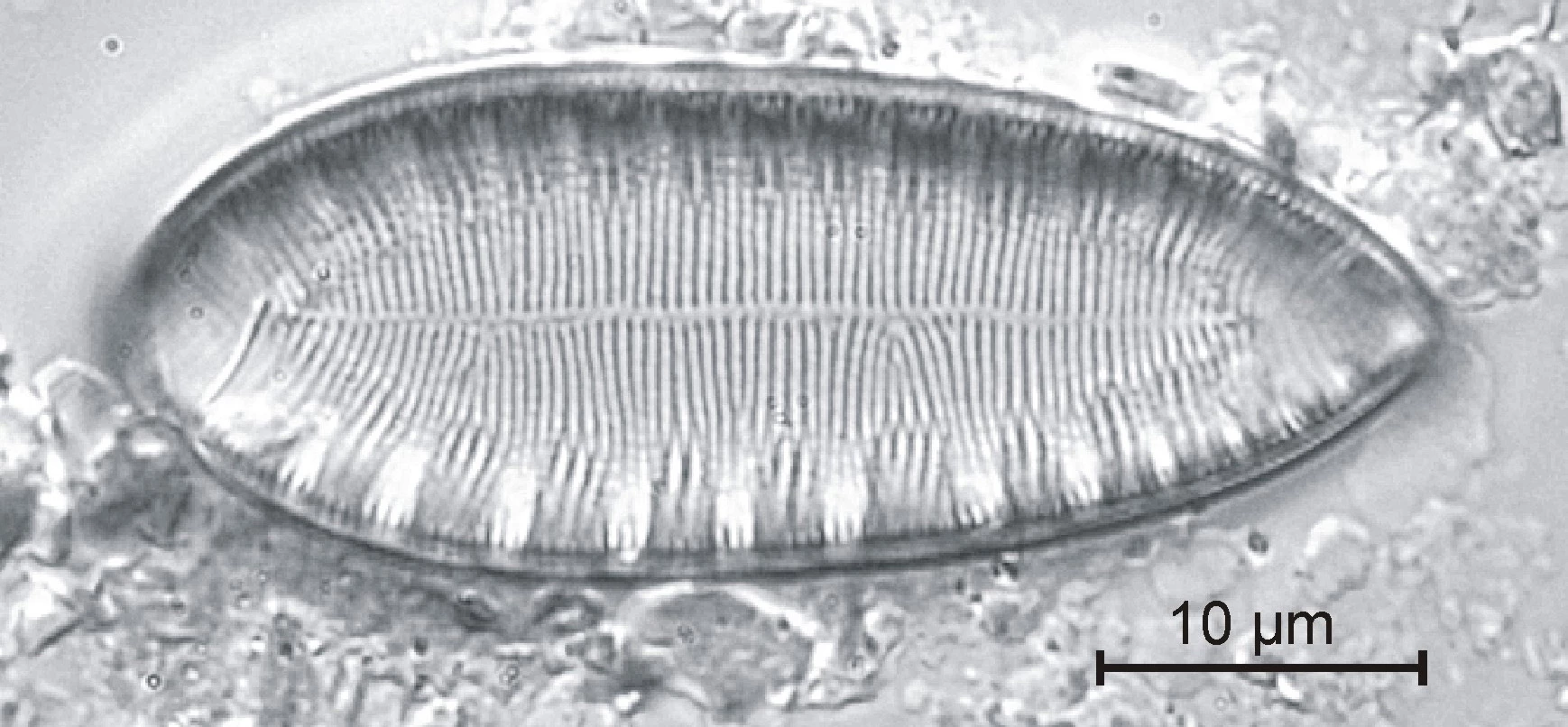

Diatoms are microscopic algae which are found worldwide in all types of aquatic habitats. Their silica cell walls make them relatively easy to collect and study and hence they are much used in studies of water quality and environmental history.

There are only few studies on diatoms from the Falkland Islands. The current research aims to provide a checklist of common species and document them photographically. A collaboration with Dr Roger Flower, University College London, Environmental Change Research Centre, who conducted several studies on Falkland diatoms, and with Prof. Bart Van de Vijver, Botanic Garden Meise, Belgium, who is an expert on freshwater diatoms from (sub-) Antarctic islands, will allow us to compile the most important species and to compare the diatom flora of the Falkland Islands to those from other South Atlantic and (sub-) Antarctic locations.

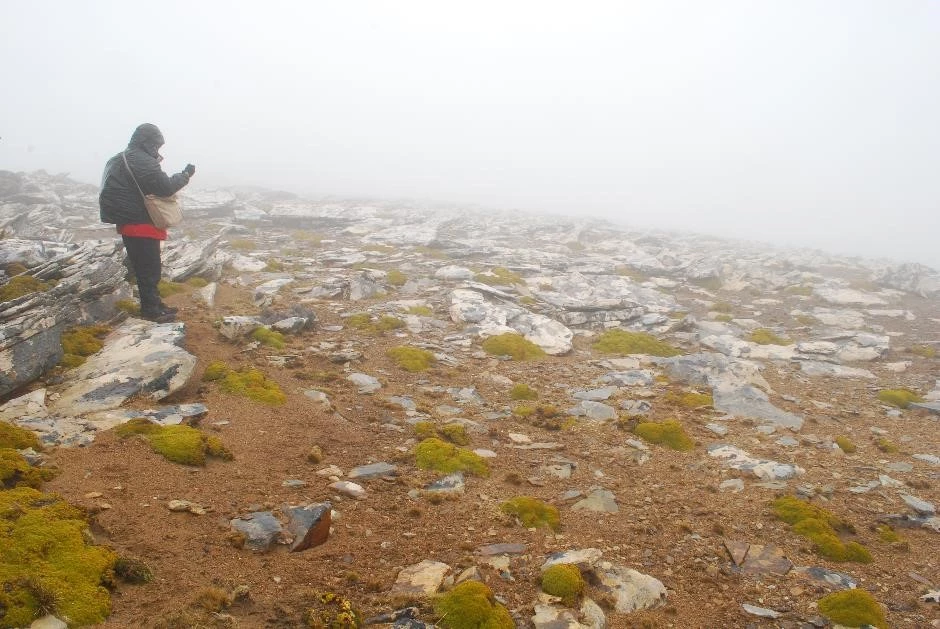

The field work took place in November 2015. Collections of diatoms were made from a range of freshwater habitats on East Falkland, West Falkland and Pebble Island. Samples were taken from ponds, streams, springs and damp terrestrial habitats. Care was taken to collect from a good range of substratum types to allow the study of the different algal communities which can vary considerably between microhabitats.

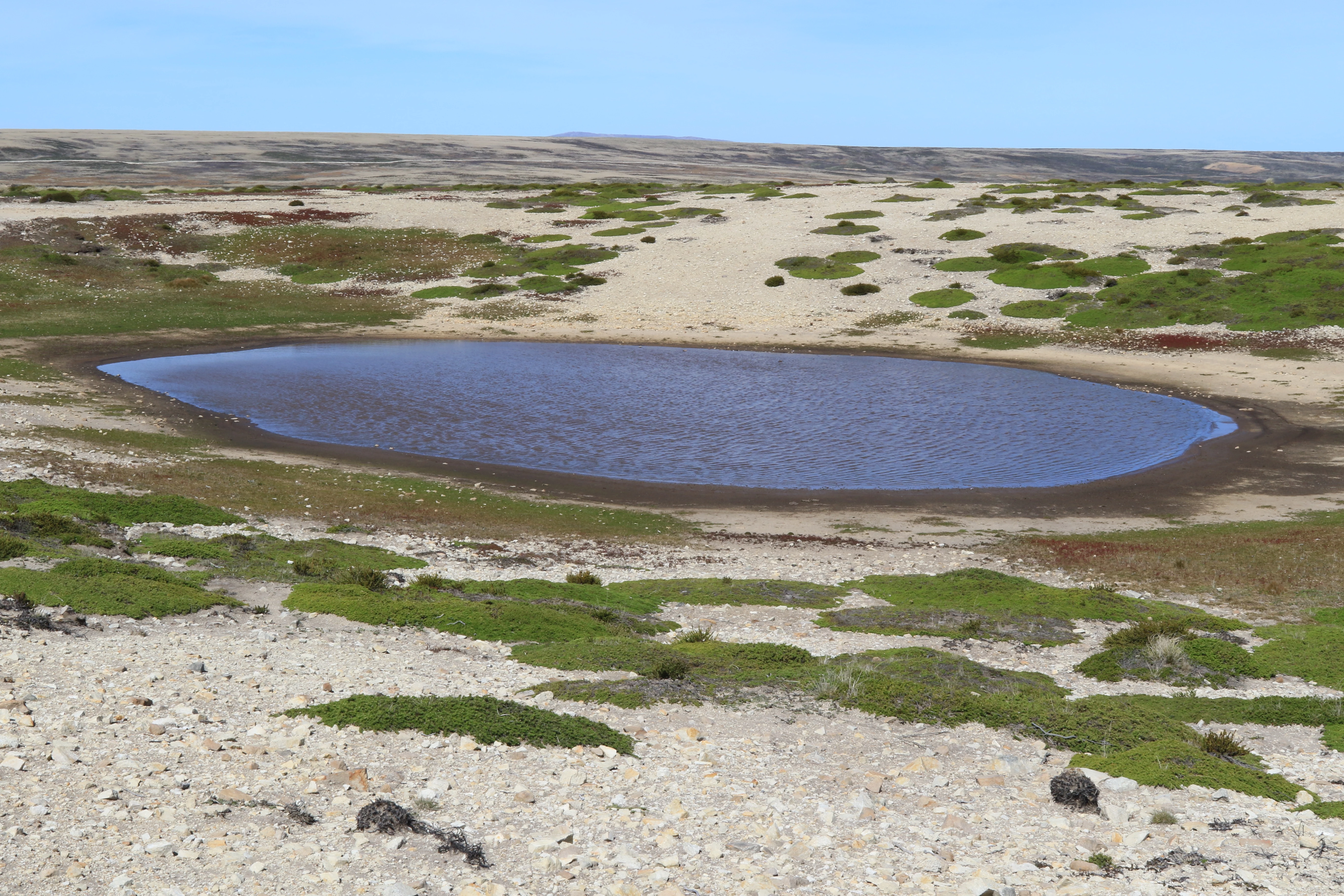

I stayed on Pebble Island for three days and had opportunities to explore both the western and eastern parts of the island. I collected from sites impacted by agriculture within the vicinity of farmland but also from remote sites away from human activities. The sites were varied and included ponds near the seashore that would receive sea spray, ponds in sand dunes and others which were certainly frequented by upland geese and other birds including penguins and therefore rich in nutrients.

Ponds on Pebble Island

In the western area of the island I took samples from various types of springs, such as a spring with stagnant water (known technically as a limnocrene), a flowing spring (rheocrene), a captured spring supplying drinking water to the Pebble Island settlement, several seepage areas and a stream.

Stream on Pebble Island

Spring on Pebble Island

It is difficult to move further afield on the island because there are no roads. However, the very friendly and supportive staff of the farm took me out in their four-wheel drive to reach the remotest corners of the island.

I then flew to West Falkland in a small aircraft. These planes are vital for transport between the different islands of the archipelago and supply the small settlements and remote farms with food and other essentials.

On West Falkland I stayed at Port Howard and explored the area in the vicinity for one day collecting from various ponds and streams. On the second day my host took me on a trip along the road to Chartres which further leads to the area around Fox Bay, providing me with ample opportunities to sample including at the Patricia Luxton Nature Reserve and in the Lakelands area.

River between Port Howard and Fox Bay, West Falkland

Pond between Port Howard and Fox Bay, West Falkland

On my return to East Falkland I visited three contrasting areas: Lafonia, a large low-lying area in the south-west which has plenty of ponds, lakes, small streams and marshy terrestrial habitats in the Cortaderia (White Grass) grassland; the Cortaderia grassland and Empetrum rubrum (Diddle-dee) plain near Volunteer Point north-east of Stanley and a more agricultural area north of Mount Kent, near Hope Cottage Farm, and along the road between Douglas Station and Salvador.

Cortaderia (White Grass) grassland of Lafonia, East Falkland

Pond in Lafonia, East Falkland

Vantan Arroyo River between Mount Pleasant Airport and Stanley, East Falkland

On the journeys to some of the areas I also collected from rivers draining the central mountain ridge, although higher areas in the mountains were not collected during this visit due to a lack of time.

River near Hope Cottage Farm, East Falkland

Pond near Douglas Station, East Falkland

I am currently processing the diatom samples in the laboratory, and the entire collection of Falkland diatom samples held at the National Museum of Wales (including samples taken by a colleague during earlier visits to the Falkland Islands) has been entered on our diatom database. Imaging and taxonomic investigations will commence soon and a visit to the Botanic Garden Meise, Belgium, to collaborate with Prof. Bart Van de Vijver is scheduled for the beginning of September.

Diatom species of the genus Surirella

Thank you to David Tatham, Chairman of the Shackleton Scholarship Fund, and other members for awarding me the scholarship; thank you to Nick Rendell, Falkland Islands Government, and to Dr Paul Brickle, Director of South Atlantic Environmental Research Institute (SAERI) for the research licence and support. Many thanks to all the landowners who freely granted access to their land.