Every object tells a story

, 6 April 2012

Inspired by the most inquisitive visitor ever who came and really tested my knowledge yesterday (perfect mental warm up for all the questions we'll get about the collections over the holidays) I thought it would be useful to give some suggestions for things to consider when exploring objects.

All objects have some kind of a story, and objects are all evidence of somewhere, something, or somebody ans as such all have stories to tell.

So when you're looking at an object for the very first time, thinking about some of these will guide your exploration:

Is it real or a model?

How old is it?

Is it man made or natural?

What might it have been used for/by whom/when/for what?

Does it remind you of anything you've seen before?

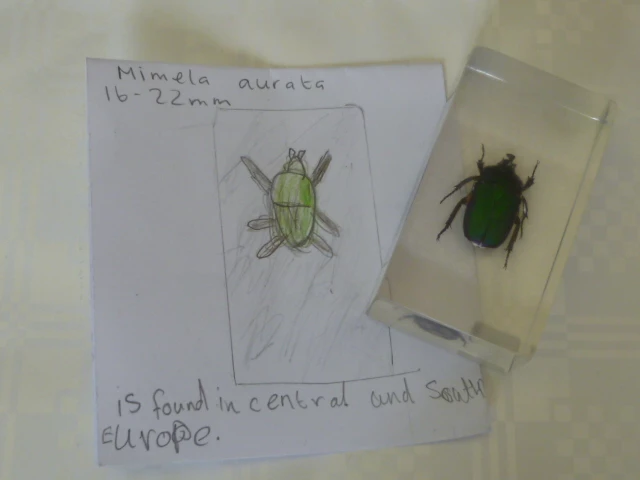

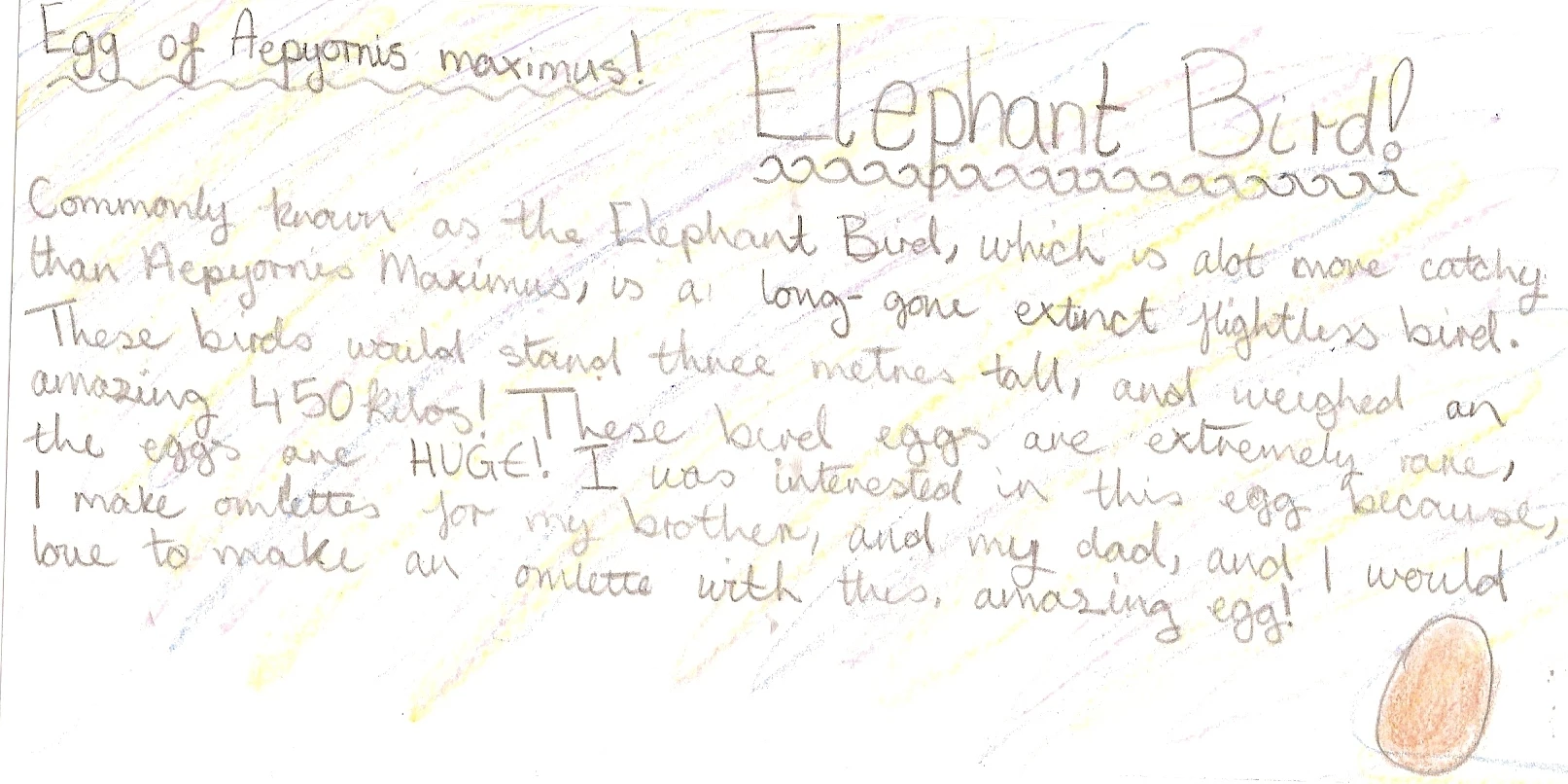

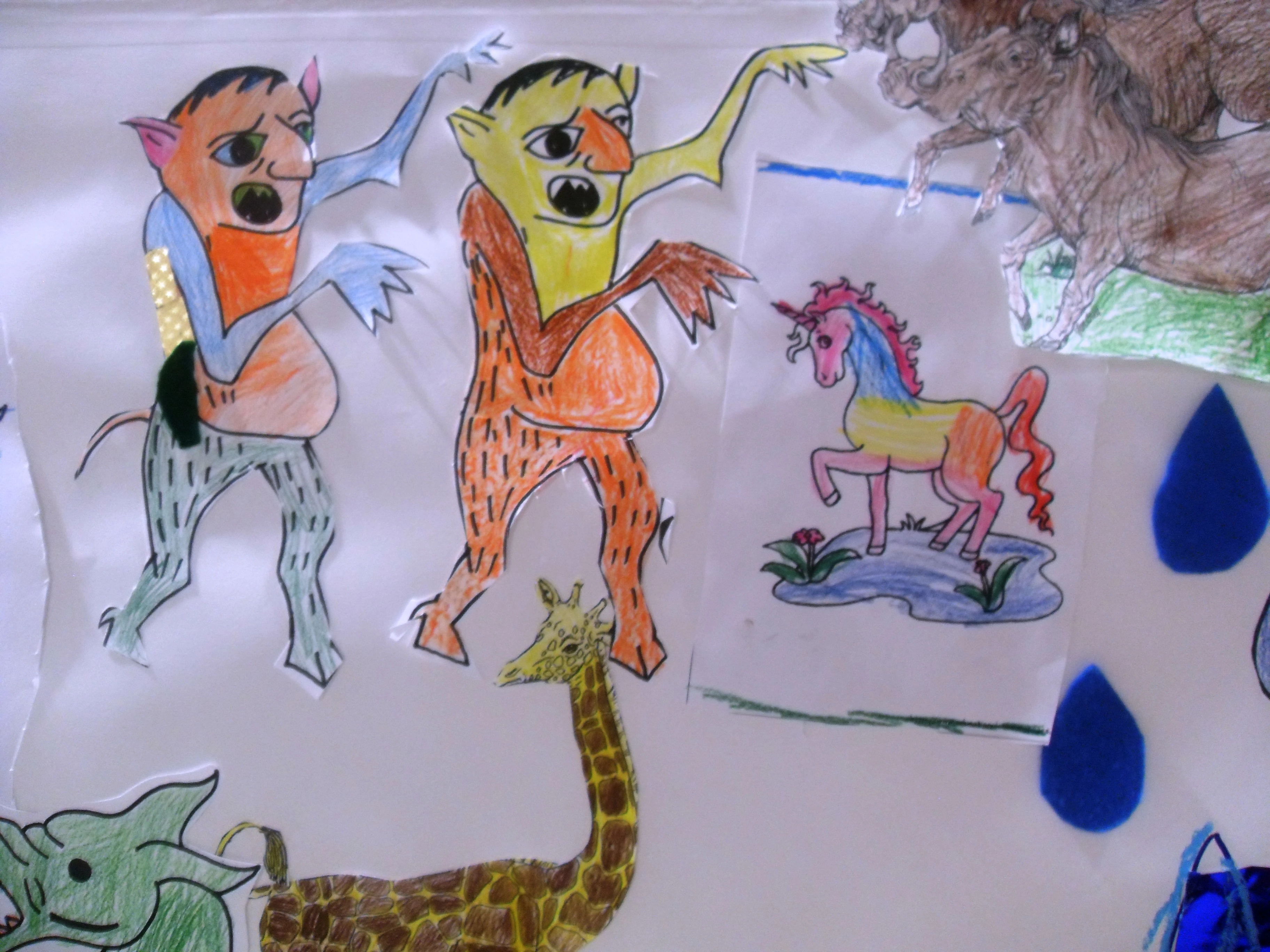

Some of our busy school visitors investigated and explored objects in the gallery, through careful questioning and research they discovered lots about their objects. Here is a selection of the labels they wrote