Celebrating Pride Month! - Queer Identity: Floral Symbolism and Community

, 19 June 2025

To celebrate Pride Month this year, some of our amazing ACPs will be hosting Pride themed workshops across some of our museums this June. As part of that celebration, we asked them to reflect on the themes and inspiration behind their workshop and what Pride means to them.

Symbolism plays a large role in queer history; a big part of this symbolism has been through the use of flowers. Whether it be a derogatory or reclaimed term or a way of signaling to other members of the community, flowers are intertwined with our history.

Violets have historically been associated with lesbianism and femininity; green carnations have been used as a way for gay men to flag each other, ‘pansy’ has been used as an insult for effeminate men, and lavender, both the colour and flower, has been used for decades as an icon of queer resistance and liberation.

Throughout the museum’s archives there are examples of this floral symbolism in protest badges and artworks, which embody the link between our history and flowers.

Violets

In the 6th century, Sappho, a poet from the island Lesbos, described her female lover as wearing a ’violet tiara’. Sappho, well-renowned for her poems, sapphic eroticism and love (indeed, she is where the word sapphic originates), influenced the language and iconography associated with lesbianism and female sexuality extraordinarily. Her use of florals in her poetry no doubt shaped queer symbolism and kinship with flowers across the following centuries.

In early 20th-century Paris, violets were a common adornment for those a part of ‘Paris Lesbos’, homosexual women who built a community with one another represented by the violets they carried, gifted each other, and were buried with.

The symbol was reborn in America when a French play being performed on Broadway, The Captive, used violets to symbolise sapphic love. In the play, a woman gifts her romantic interest a bouquet of violets; this led to outrage and scandal across New York, the play being shut down, the sale of violets plummeting and a state law dealing with ‘obscenity’ being introduced. Despite the pushback, Parisian supporters of the play wore violets on their lapels and belts.

The colour violet has also had significant presence in LGBTQ+ history, with it being present on the first pride flag– created in 1978 by artist Gilbert Baker in California, USA- and it still being present on the traditional 6-stripe rainbow pride flag and progress pride flags and many other iterations. Violet typically symbolises the spirit of the LGBTQ+ community, a fitting meaning for a symbol that has lasted and spread for over a millennium.

Pansies

In the early 20th century, there were many floral terms used to describe an effeminate (and therefore ‘gay’) man. ‘Daisy’, ‘buttercup’ but, perhaps most notably, ‘pansy’. The term ‘pansy craze’ was used to describe the underground queer nightlife and drag scene in places like New York, Los Angeles and Chicago, with similar scenes being seen across European cities like London, Berlin and Paris before the rise of authoritarian politics and Nazism. The onset of the depression, the beginnings of World War II and the end of American prohibition saw an end to the short period of visibility for the LBGT community, but the icon that is the pansy has prevailed. Still occasionally used as an insult by the some, ‘pansy’ has taken on a life of its own being used as a term of endearment.

Lavender

The colour lavender has been distinctly used to represent the LGBTQ+ community in many different eras and places, especially in the 20th century, but the flower was also used as a lesser-known symbol for homosexual love. Lesbians gifted lavender as a covert way of expressing their romantic interest in one another, and the flower became increasingly entwined with queer identity throughout the mid-1900s.

The ‘lavender scare’ was a time that parallelled the ‘red scare’ in 1940s and 50s America when those perceived to be a part of the community were fired from their jobs, often when working for the American government, due to their supposed ‘communist sympathies’ because of their sexuality.

The colour lavender was used to symbolise queer identity once again a month after the pivotal Stonewall Riots, in July 1969, as lavender sashes and armbands were handed out by the Gay Liberation Front in a ‘gay power’ march across New York City.

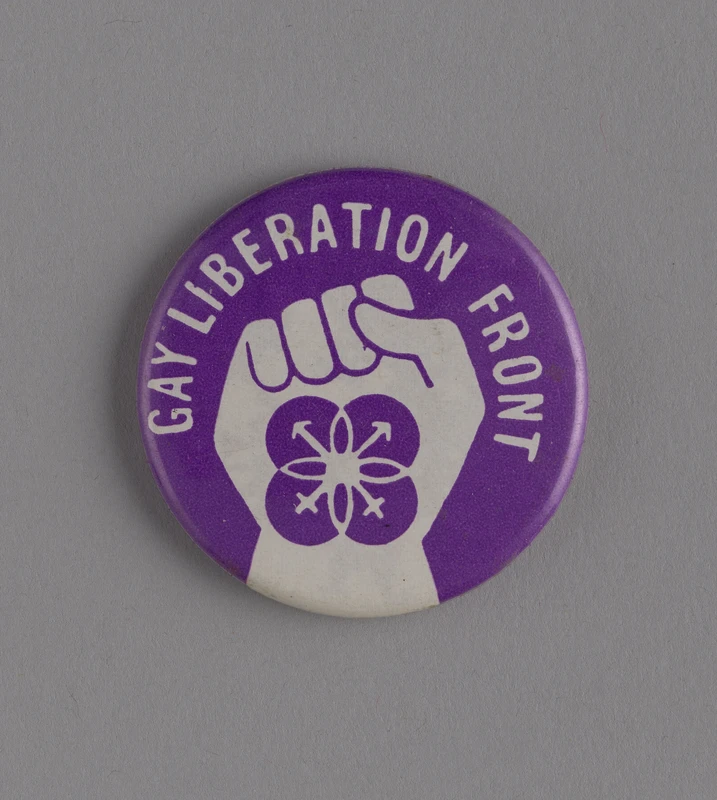

The Gay Liberation Front was the first recorded gay organisation to use ‘gay’ in its name, and its existence and work marked a turning point for the LGBTQ+ community across the globe. One of their first badges used a purple flower with the male/female symbols detailing its petals, whilst resting on a raised fist, a historic symbol of protest. The badge, which can currently be seen at St Fagans’ Wales is: Proud gallery.

A radical feminist group, ‘the Lavender Menace’, was an informal group that protested the exclusion of lesbians and sapphic women in feminist movements in the early 1970s. The term was first used by feminist writer and activist Betty Friedan, who described lesbians as a ‘lavender menace’ that would undermine the entire women’s liberation movement. The name was adopted by the group as a way of reclaiming the negative language used about them, and they are widely associated as being integral to the founding of lesbian feminism.

Carnations

Oscar Wilde, the Victorian author, famously popularised the green carnation in the late 19th century. The flower was dyed by watering it with water laced with arsenic. He pinned one to his left lapel, a style that keeps cropping up as we analyse the use of these flowers as a way to subtly signal to others that he was a rebellious individual, a man who loved other men, in a society that condemned and criminalised male homosexuality– Victorian London.

Eventually, after the publication of a book written anonymously, ‘The Green Carnation’, Wilde was arrested and jailed for gross indecency. Wilde outright denied writing the book, but his work popularising the carnation years prior was enough for authorities to pin the work on him.

Despite this, the carnation prevailed, and it is still a recognised symbol today, albeit a less popular one.

Roses

The rose is a well-known symbol of love, and of course this extends to queer love. In 1960s Japan the rose became an iconic symbol for gay men, even influencing the language they use to describe gay men today. Bara, meaning rose, is a commonly used term for the community.

Roses are also special to the transgender community, especially on Trans Day of Visibility (March 31st), when the phrase ‘give us our roses while we are still here’ is echoed. It means that we should celebrate the lives of trans people, of trans WOC, rather than simply mourning them when they are killed. It is about decentring grief in the trans community and celebrating life whilst amplifying transgender voices. The rose is an important symbol of this, showing appreciation and joy for transgender people.

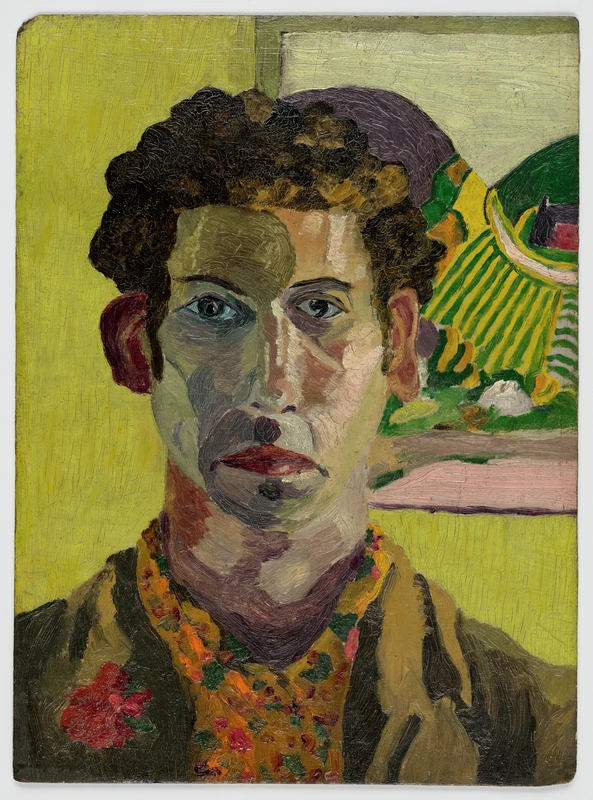

In this painting, a self-portrait by gay artist Cedric Morris while he lived with his partner in Cornwall, Morris is depicted with a rose pinned to his lapel. Whether this is symbolic of his love or homosexuality is unclear, but it is an obvious example of the tie between the LGBTQ+ community and flowers throughout the ages. Morris was relatively open about his relationship with fellow artist Arthur Lett-Haines, despite homosexuality being illegal at the time.

Flowers are still an integral part of our community and a beautiful way to honour our history. A piece from the museum's archives I find particularly valuable is the flowers worn during the marriage of two gay men, Federico Podeschi and Darren Warren, on the day same-sex marriage was legalised in England and Wales. These flowers symbolise so much that the queer community has fought for: the right to be legally recognised. But they remind us that there is so much further to go, especially in these uncertain times and how recently it was that we gained some basic rights.

My workshop, run both this year and last for Pride, encourages you to connect with our history through the medium of printmaking. Last year we created a banner to be marched at Pride Cymru, and now I will invite participants to create a piece of art to take home or gift to another.

Elizabeth Bartlett @liz_did_stuff on Instagram

Amgueddfa Cymru Producers [ACPs] are a group of young people aged 16 – 25 living in or from Wales who collaborate with the Museum through participatory and paid opportunities.

This is a space to deepen knowledge and to ensure that cultural and heritage spaces are more representational of the young people and their many cultures that make up Wales today. We are here to make heritage relevant!

We explore art, heritage and identity, environmentalism, natural science, social history and archaeology through our collections and by co-producing events, workshops, exhibitions, digital media, publications, development groups and more! Our ACPs work closely with departments across the Museum to help us deepen representation within our collections and programming, that reflects all communities in Wales. This includes expanding our LGBTQ+ collection, decolonising our collections and gathering working-class history through oral histories. ACPs can also bring their own ideas or topics they wish to explore through our collections!

You can sign up to our mailing list here to keep up to date with news and new opportunities.

If you have any queries you can email us on bloedd.ac@museumwales.ac.uk. Follow us on Instagram to keep updated on all things Bloedd!