Cig Oen a Chig Dafad

, 24 March 2016

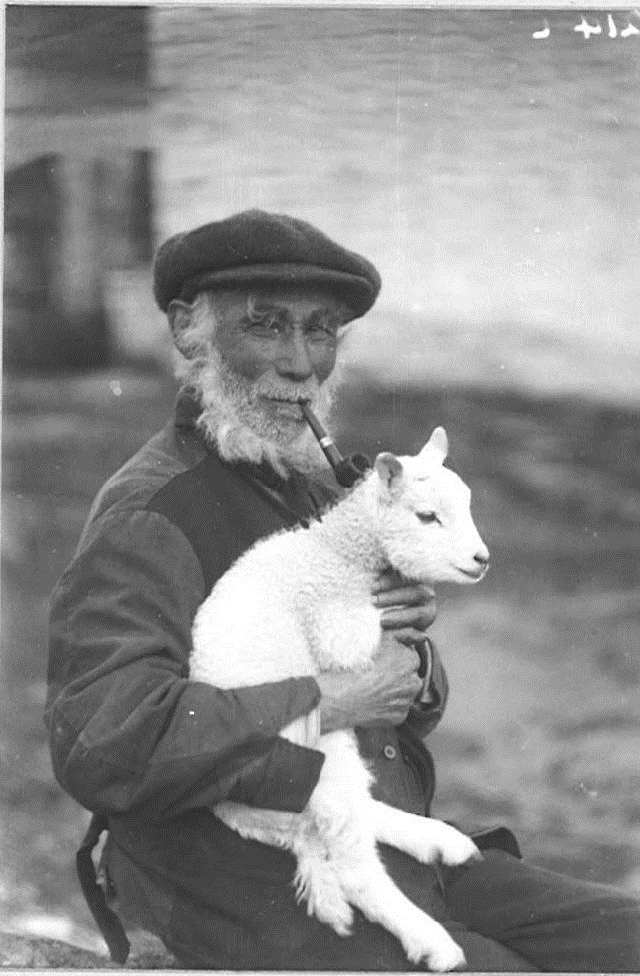

Dwi’n siŵr eich bod, fel finna yn dotio gweld yr ŵyn bach adeg hyn o'r flwyddyn, ac wedi bod yn cadw llygaid ar y diweddaraf o'r Sgrinwyna sy'n cofnodi'r genedigaethau ar fferm Llwyn-yr-eos, yma yn Sain Ffagan.

Erbyn heddiw ystyrir cig oen fel ein danteithfwyd cenedlaethol, a dwi’n siŵr y bydd amryw ohonoch yn mwynhau gwledda ar gig oen wedi ei rostio dros Sul y Pasg. Be sy’n syndod yw mai tan yn gymharol ddiweddar, ni fwytawyd llawer o gig oen yma yng Nghymru. Cedwid defaid ar gyfer eu gwlân a’u llefrith, nid ar gyfer eu cig. Dim ond ar achlysuron arbennig y bwytawyd cig oen, gan ei fod yn fwy proffidiol i gneifio a gwerthu gwlân y ddafad.

Wrth chwilota trwy’r archif, prin iawn yw’r ryseitiau sy’n cynnwys cig oen. Ond yr hyn sydd yn rhan o’n traddodiad, ac sy’n profi dadeni ar hyn o bryd yw cig dafad – sef cig o anifail a gedwid rhwng tair a phum mlynedd. Tan y 1940au, roedd cig dafad yn ffefryn ar draws Prydain a’r consensws oedd bod ei flas a’i ansawdd yn rhagori ar gig oen. Wrth deithio o amgylch Cymru ym 1862, fe brofodd George Borrow gig dafad am y tro cyntaf, a bu’n canu ei glodydd:

The leg of mutton of Wales beats the leg of mutton of any other country, and I had never tasted a Welsh leg of mutton before. Certainly I shall never forget that first Welsh leg of mutton which I tasted, rich but delicate, replete with juices derived from the aromatic herbs of the noble Berwyn, cooked to a turn, and weighing just four pounds ... Let anyone who wishes to eat leg of mutton in perfection go to Wales.

George Burrow Wild Wales: Its People, Language and Scenery, 1862

Felly pam fod cig dafad wedi mwy neu lai diflannu o’n basgedi siopa a’n bwydlenni? Gyda gostyngiad ym mhris gwlân yn ystod degawdau cyntaf y 1900au, roedd yn talu i ffermwyr werthu ŵyn gwrywaidd ar gyfer cig, yn hytrach na’u cadw i roi gwlân. Rhaid cofio hefyd fod cig dafad yn cymryd tipyn yn hirach i'w goginio, felly nid yw'n syndod iddo gael ei ddisodli gan gig oen sy'n yn cymryd chwarter yr amser.

Dros y degawd diwethaf, fodd bynnag, mae cig dafad wedi cynyddu yn ei boblogrwydd unwaith eto, gyda mwy o fwytai, ffermydd, siopau cig a chogyddion enwog yn gwerthu a hyrwyddo'r cig arbennig yma. Er ei fod ar gael drwy’r flwyddyn, mae ar ei orau rhwng mis Hydref a Mawrth. Felly tymor cig oen yw hi ar hyn o bryd, ond erbyn yr Hydref, cofiwch edrych allan am gig dafad yn ei siop cig lleol.

Dyma rysáit o’r archif, mae’r dull o goginio’r pryd hwn yn amrywio, ond dyma fersiwn teulu o Garnfadrun, Llŷn:

Tatws Popty

darn o gig dafad

tatws

nionyn

dŵr

Llenwi gwaelod y tun cig â thatws a nionod, a’u gorchuddio â dŵr. Rhoi darn mawr o gig eidion neu gig dafad ar wyneb y tatws a rhostio’r cwbl yn y popty.