Weather Warnings

, 7 March 2018

Hello bulb buddies,

What an interesting time to be studying and observing the weather! Most of you will have had snow and high winds this last week. I understand that many schools were closed, and that conditions in the school grounds may have meant you weren’t able to collect weather data on days that you were in school.

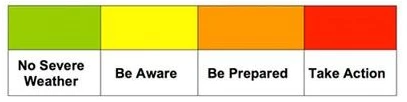

It’s likely that you’ve heard people talking about weather warnings a lot over the last week. Weather warnings are released by the MET Office (the UK’s official weather service) and are colour coded (green, yellow, amber and red) to indicate how extreme the weather will be in different areas.

Green: weather is not expected to be extreme.

Yellow: possibility of extreme weather so you should be aware of it.

Amber (orange): strong chance of the weather effecting you in some way, so be prepared.

Red: extreme weather expected, plan ahead and follow the advice of the emergency services and local authorities.

The Met Office also use symbols to indicate what type of weather to expect. For example, the symbols to the right show (in order) a red warning for rain, green for wind, green for snow, amber for ice and green for fog. This means there will be heavy rain and that you should prepare for ice. Why not have a look at the Met Office website and see what the weather forecast is for where you live?

Amber and red warnings for wind, snow and ice were given for many parts of the UK last week as storm Emma and the ‘Beast from the East’ collided. The Met Office warn us about bad weather so that we can prepare for it. This is because extreme weather (such as strong winds and ice) can cause difficulties and make it hard to travel. Roads and train lines can close, flights can be cancelled, and walking conditions can be dangerous.

What was the weather like where you live? If you weren’t able to collect weather records you can enter ‘no record’ on the online form, but please let me know in the comment section what the weather was like! You can also let me know how your plants are doing and whether they have flowered!

Keep up the good work Bulb Buddies,

Professor Plant

Comments about the weather:

Ysgol Beulah: Roedd eira yn pot ni :)!!!!!!!!!.

Ysgol Carreg Emlyn: Mae hi wedi bwrw eira yma heddiw.

Ferryside V.C.P School: mae wythnos hyn wedi bod yn bwrw lot

Broad Haven Primary School: Snow Hail sleet sun rain gales . We have seen them all.

St Robert's R.C Primary School: We had a cold week this week.

Peterston super Ely Primary School: Lots of snow on Friday

Steelstown Primary School: Once again northern Ireland has been hit by a cold patch but Derry has once again missed out on heavy snowfall roll on spring.

Severn Primary: Some other places got some snow and it was really cold on Thursday when we went out for Games because of the wind. Hope we get snow!

St Paul's CE Primary School: WINDY AND COLD SNOW SHOWERS

Canonbie Primary School: We had snow again this week and lots of rain. Little signs of life springing through but no flowering bulbs yet.

Canonbie Primary School: This week has been a bit mixed weather wise. We had freezing conditions and snow on Tuesday but milder conditions by Friday. Typical British weather.

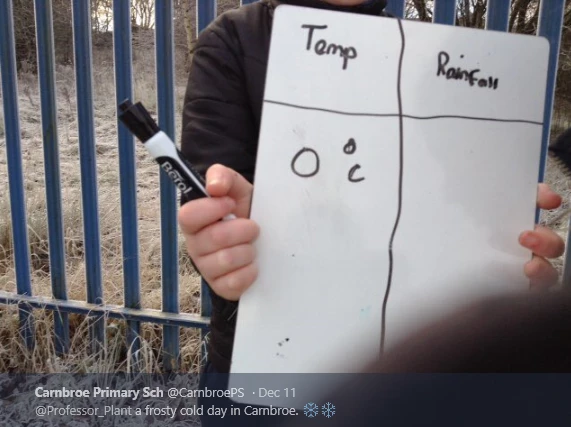

Carnbroe Primary School: Hi Professor Plant, we were off all week except for Thursday and Friday. The weather this week has been cold and icy.

Peterston super Ely Primary School: Snow days on Thursday and Friday

Onthank Primary School: No record of result due to snow days.

Auchenlodment Primary School: The Beast from the East hit this week! There was lots of snow and we were off school, yippee!

St John's Primary School: School was closed on Thursday due to weather conditions.

Fleet Wood Lane Primary School: School closed because of snow on Weds – Fri.

Carnforth North Road Primary School: The weather this week has been very cold and windy. The children have had to wrap up warm to gather the data.

Portpatrick Primary School: Very cold first thing - frozen ground, but no snow.

Inverkip Primary School: Hi professor plant Monday we had ALOT of rain but every other day it didn't rain at all. The temperature was warm then it dropped down but steadied up at the end of the week.

Steelstown Primary: We are starting to get some warm weather and some of our bulbs are growing.

Arkholme CE Primary School: It was very cold and on some days it was frosty.

St Andrew's RC Primary School: The rain gauge was broken by the frost, we have ordered a new one. This is why we have no rainfall for Wednesday, Thursday or Friday.

Comments about your plants:

Ysgol Beulah: Roedd y tywydd yn oer iawn felly dydy'r blodau ddim wedi blaguro eto.

Ysgol Y Traeth: Mae sawl un o'r blodau wedi dechrau tyfu a rhai wedi dechrau agor yn araf. Mae 14 crocws wedi tyfu a 27 daffodil wedi tyfu.

Carnbroe Primary School: Hi Professor Plant, our bulbs still have not bloomed yet. The weather this week has been changeable. It has been wet, really really cold and icy and although the sun is out it's been cold.

Ysgol Bro Pedr: Many bulbs making an appearance now - a very cold week

Peterston super Ely Primary School: Meghan's crocus has finally flowered! Hopefully when we return from our half term holiday a few more will have flowered too.

Peterston super Ely Primary School: The children are very excited this week as one of our crocus bulbs has finally flowered!

Darran Park Primary: The temperature is still very cold. Our daffodils haven't grown but our crocus have a little bit.

Inverkip Primary School: Mon - Wed school holidays so no data collected. The bulbs are growing well in the pots but not in the ground yet. None have started to flower.

Pembroke Primary School: Looks like I planted two crocus and 1 daffodil. When I saw mine I was surprised.

Pembroke Primary School: This was the first in our class. T has now left the school. The pot wasn't full to the top with compost so this may have resulted in it flowering early.

Auchenlodment Primary School: Got colder this week with very little rainfall. Most of the bulbs have begun to sprout!

Stanford in the Vale Primary School: Beautiful deep purple flower.

Ysgol Bro Pedr: The first crocus opened over our half term.

Bacup Thorn Primary School: Monday and Tuesday were teacher training days at Thorn. We are back and ready to measure! The children noticed some of our bulbs are making a slight appearance!!