Capturing the Past – Segontium Roman Fort in Photographs

, 21 September 2017

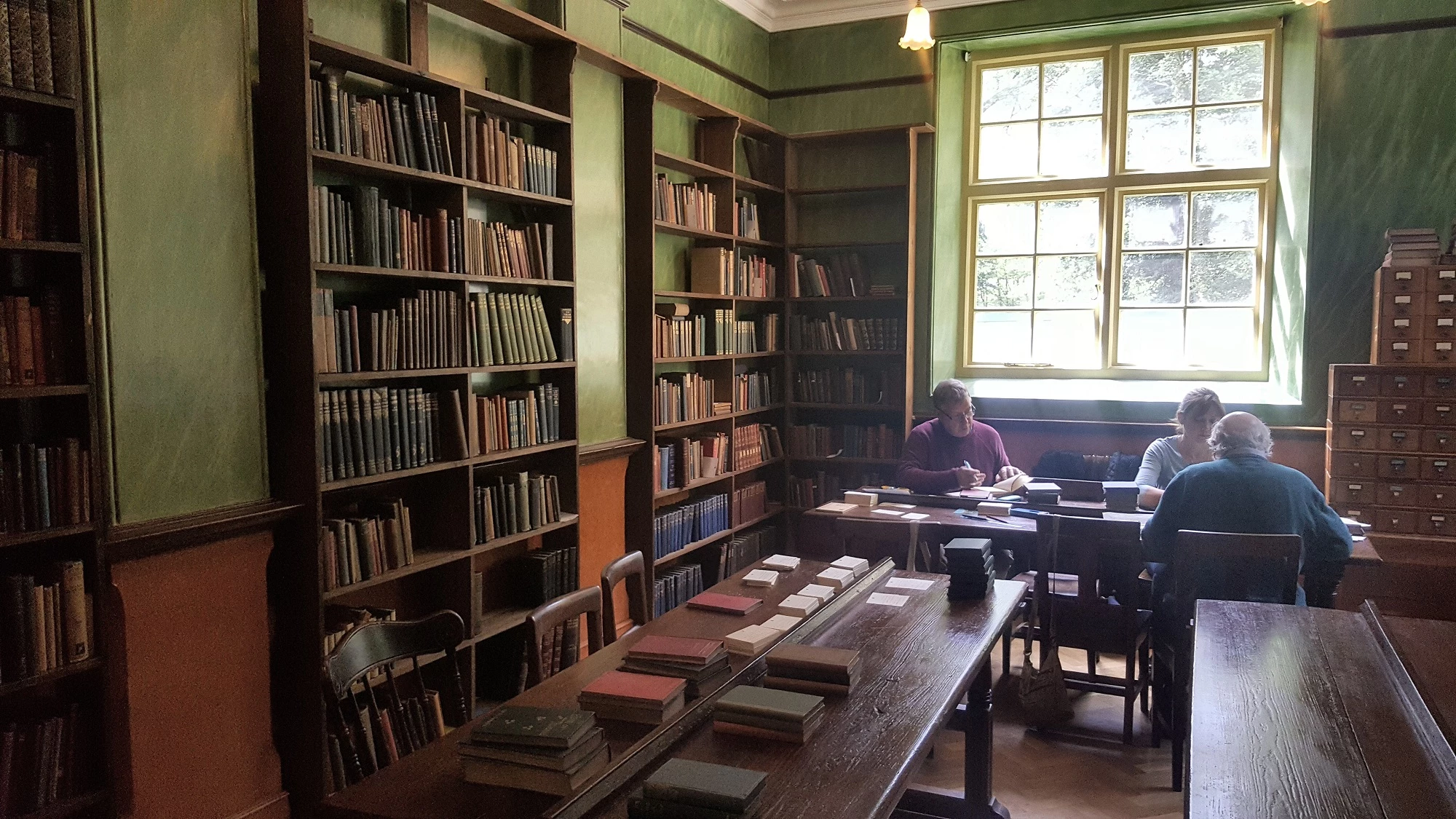

The photography department at Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales looks after images for all of the seven museum sites including the Archaeology department. That means taking new photographs of archaeological objects, and scanning historical photographs (e.g. prints and slides).

Here’s an example of how both are used.

Segontium Roman Fort, Caernarfon

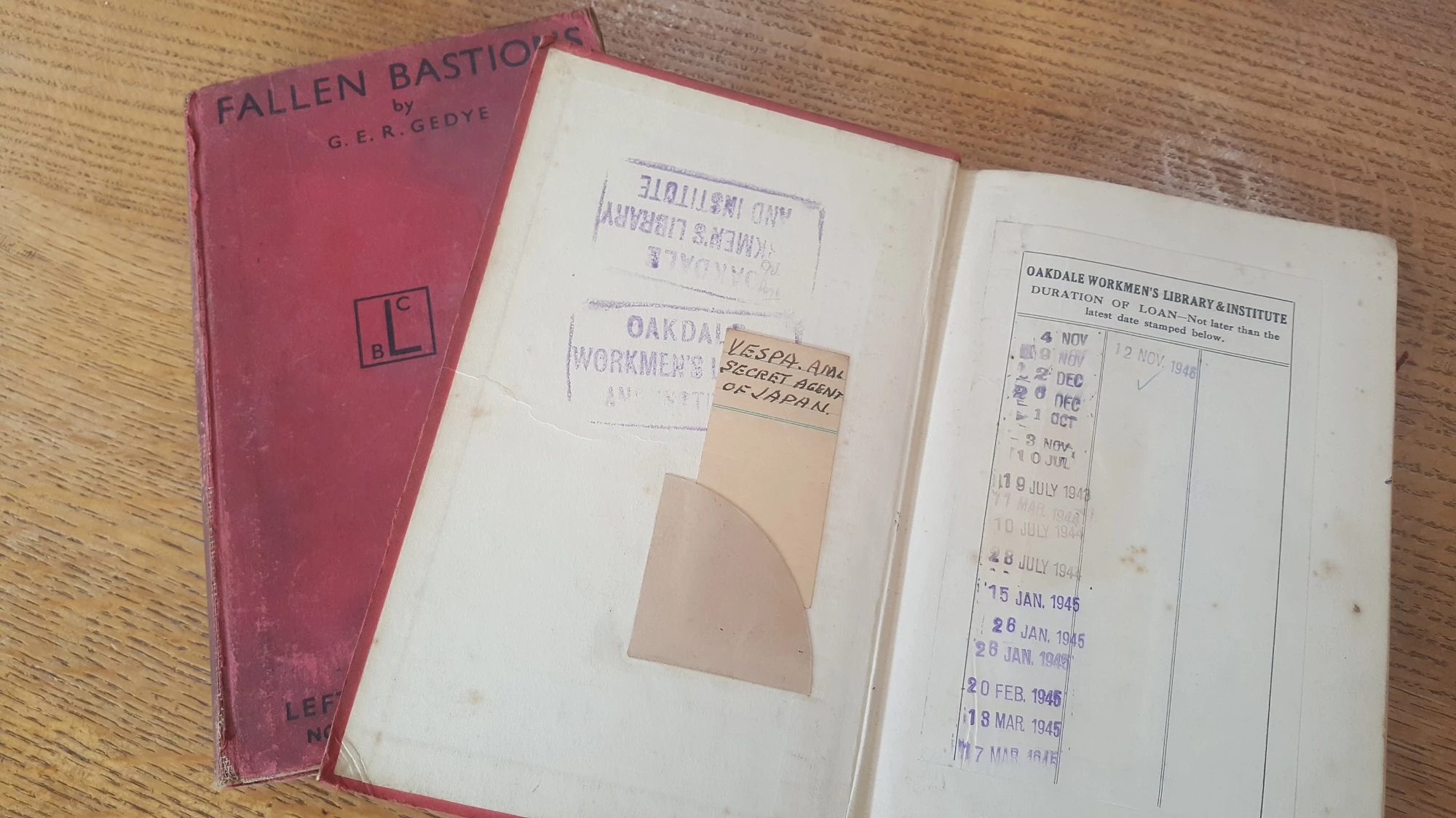

These photos from the 1920s show the excavations at Segontium led by Sir Mortimer Wheeler, the then Keeper of Archaeology and later Director of National Museum Wales. They were scanned from glass plates. Here’s a few of the 102 images from this collection:

Cellar in the Headquarters building (praetorium)

Headquarters building (praetorium) during excavations in the 1920s

Sir Mortimer Wheeler (left) showing visiting dignitaries around the site including Lady Lloyd George (front right)

The photographs may be of use to modern archaeologists interpreting the site, but personally I like spotting the shadow of the photographer and his tripod (we’ve all managed to do that haven’t we?) and checking out those fabulous 1920s hats!

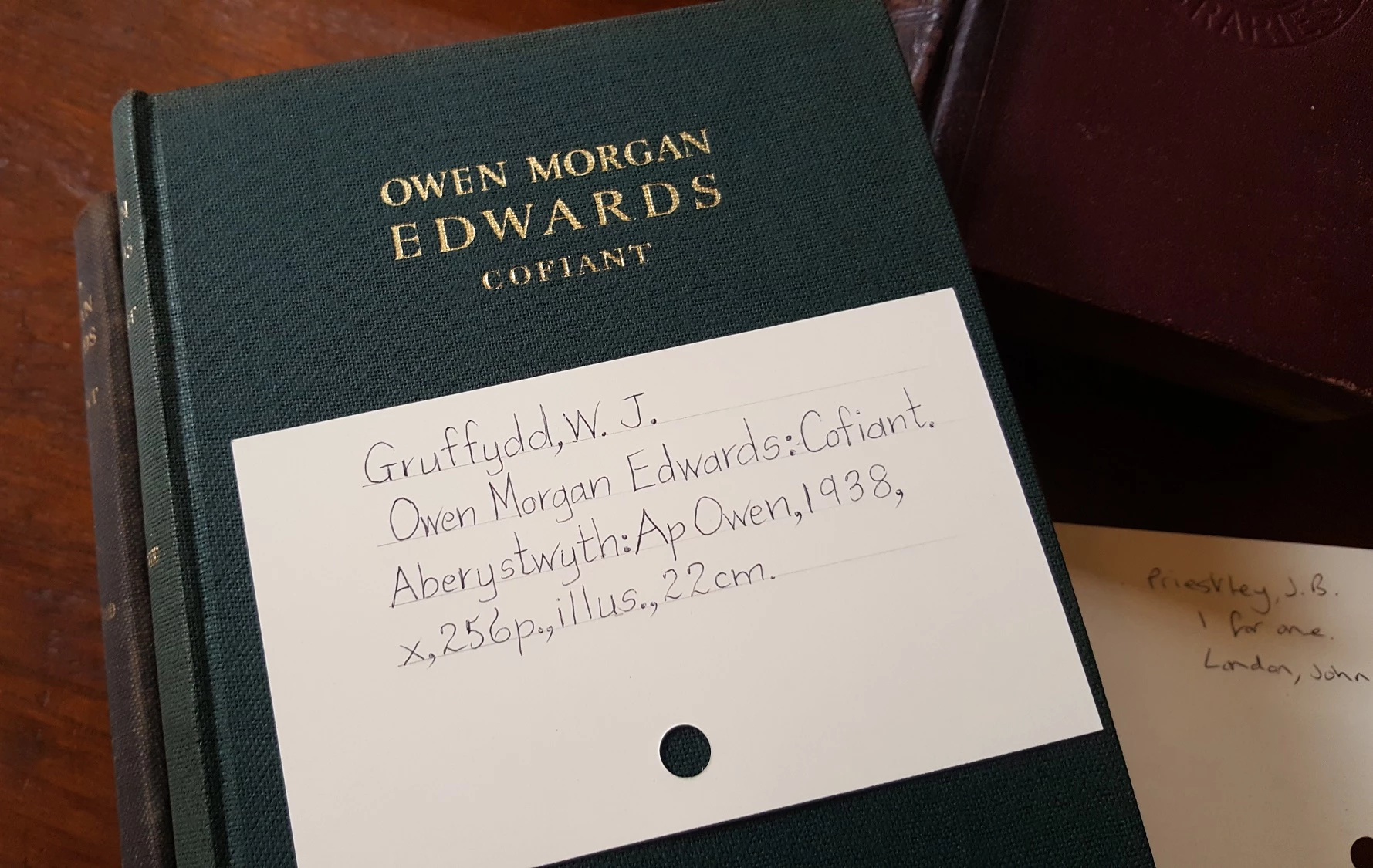

Here’s where modern photography comes in. The following images were taken recently of objects from the 1920s excavations.

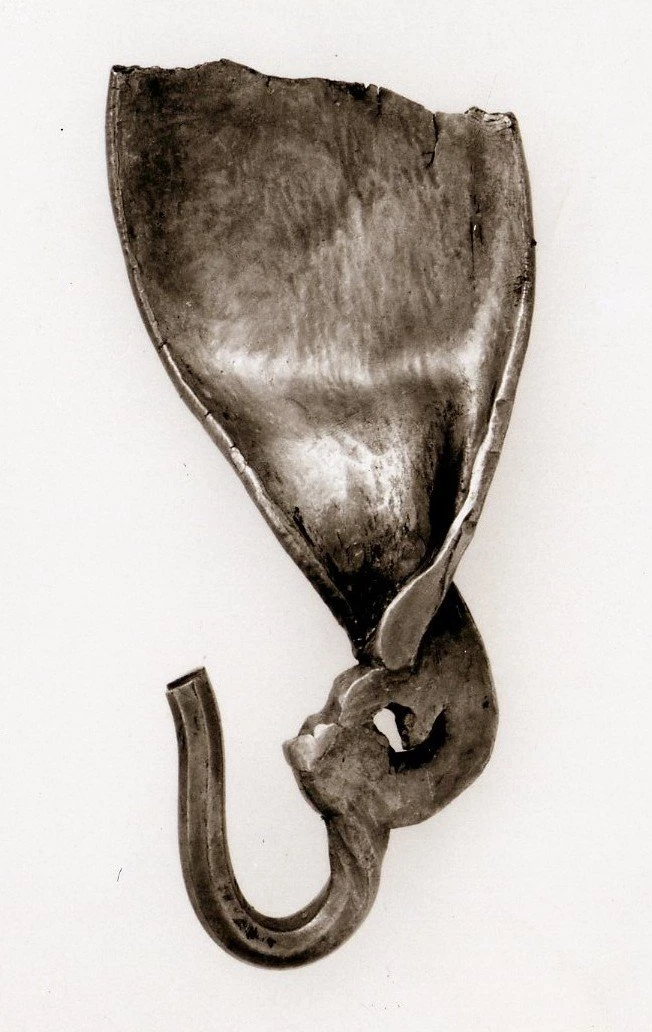

Flagon found at Segontium, but produced in Oxfordshire will be on display in the new galleries at St Fagans National Museum of History

The Goddess of war must have protected someone in their time of need, in return he vowed to dedicate an altar to her which was found in the strong room of the Headquarters building. It reads: To the goddess Minerva Aurelius Sabinianus, actarius, willingly and deservedly fulfilled his vow.

The images are digitally archived so that they’re accessible for use in exhibitions, publications, presentations and online.

Some of the finds from Segontium will be on display in the new galleries at St Fagans National Museum of History opening in 2018.

You can see more historic photographs here.

Learn more about Segontium Roman Fort on Amgueddfa Cymru’s website or on the Cadw website.

With support from the players of People’s Postcode Lottery, we’re working hard getting our collections online so you can search our object database and see information and images of the collections for yourself.