Continuing the international year of the periodic table of chemical elements, for September we have chosen carbon, the element which – in coal - has arguably had the most influence on the shaping of the built landscape and culture in Wales.

The Welsh Coalfields

For around 150 years the coal industry has dominated the industrial, political and social history of Wales. Between 1801 and 1911 the population of Wales quadrupled from 587,000 to 2,400,000. This was almost entirely due to the effects of coal mining: either directly through the creation of colliery jobs or through industries reliant on coal as a fuel (eg. steel-making).

There are two major coalfields in Wales, one in the north-east of the country and one in the south. North Wales produced mostly high volatile, medium to strong caking coal, and the coalfield has a long history of production. By 1913, it was producing around 3,000,000 tons per annum but went into a slow decline afterwards. The last colliery in the area, Point of Ayr, closed in 1996.

The south Wales coalfield is more extensive than that of north Wales. It forms an elongated syncline basin extending from Pontypool in the east to Ammanford in the west, with a detached portion in Pembrokeshire. The total area covers some 1,000 square miles.

The south Wales coalfield is famous for its variety of coal types, ranging from gas and coking bituminous coals, steam coals, dry steam coals and anthracite. They had a wide range of uses: domestic, steam raising, gas and coke production and the smelting of copper, iron and steel.

Loose jointed and friable roof conditions were more commonplace in south Wales than other UK coalfields which resulted in numerous accidents from falls of roof and sides. The deeper seams are also very ‘fiery’ leading to numerous disasters. Between 1850 and 1920, one third of all mining deaths in the UK occurred in Wales. Between 1890 and 1913 alone there were 27 major UK mining disasters, thirteen of which occurred in south Wales including the 1913 explosion at the Universal Colliery, Senghenydd where 439 men died – the largest loss of life in a UK mining disaster. North Wales was largely free of major disasters but, in 1934, an explosion at Gresford Colliery killed two hundred and sixty-six men, the third worst disaster in Welsh mining history.

South Wales steam and anthracite coal differ from other coal seams due to the presence of numerous partings (‘slips’) which lie at an angle of about 45 degrees between floor and roof. This made the coal relatively easy to work as the coal fell in large blocks. However this large coal was coated with fine dust which was the prime cause of pneumoconiosis, a disease which was more prevalent in south Wales than all other UK coalfields. In 1962, 40.7% of all south Wales miners were suffering from the disease.

A close relationship grew up between coal mining and the local community. Villages were virtually single occupation communities. In Glamorgan and Monmouthshire half of all adult male workers were directly involved in the coal industry, while in places such as the Rhondda and Maesteg, the proportion could be as high as 75%.

Because of the peculiar geology and geography, south Wales was slow to unionise. However, following the humiliating defeat after the 1898 coal strike, there arose a need for unity and in 1914 the South Wales Federation became the largest single trade union with almost 200,000 members.

From the early 1920s until WW2, the Welsh coalfields suffered a prolonged industrial recession due to the changeover to oil by shipping and the development of foreign coalfields. The numbers of miners fell from 270,000 to 130,000. The industry was nationalised following the war and experienced tremendous changes with the introduction of new techniques and equipment. There was now a greater emphasis on safety, but the coalfields were still dangerous places. In 1960, 45 men died in Six Bells Colliery, 31 died in Cambrian Colliery in 1965 and, perhaps most tragically of all, 144 people died when a tip collapsed on Aberfan, including 116 children.

By the 1980s the threat of mass pit closures arose. In March 1984 the last major strike began and continued for twelve months. Following the defeat of the National Union of Mineworkers, mines began to close on a regular basis. By the mid-1990s, there were more Welsh mining museums than working deep mines. The last deep mine, Tower Colliery, closed in January 2008. One of the most important influences on Welsh social, industrial and political life has now vanished.

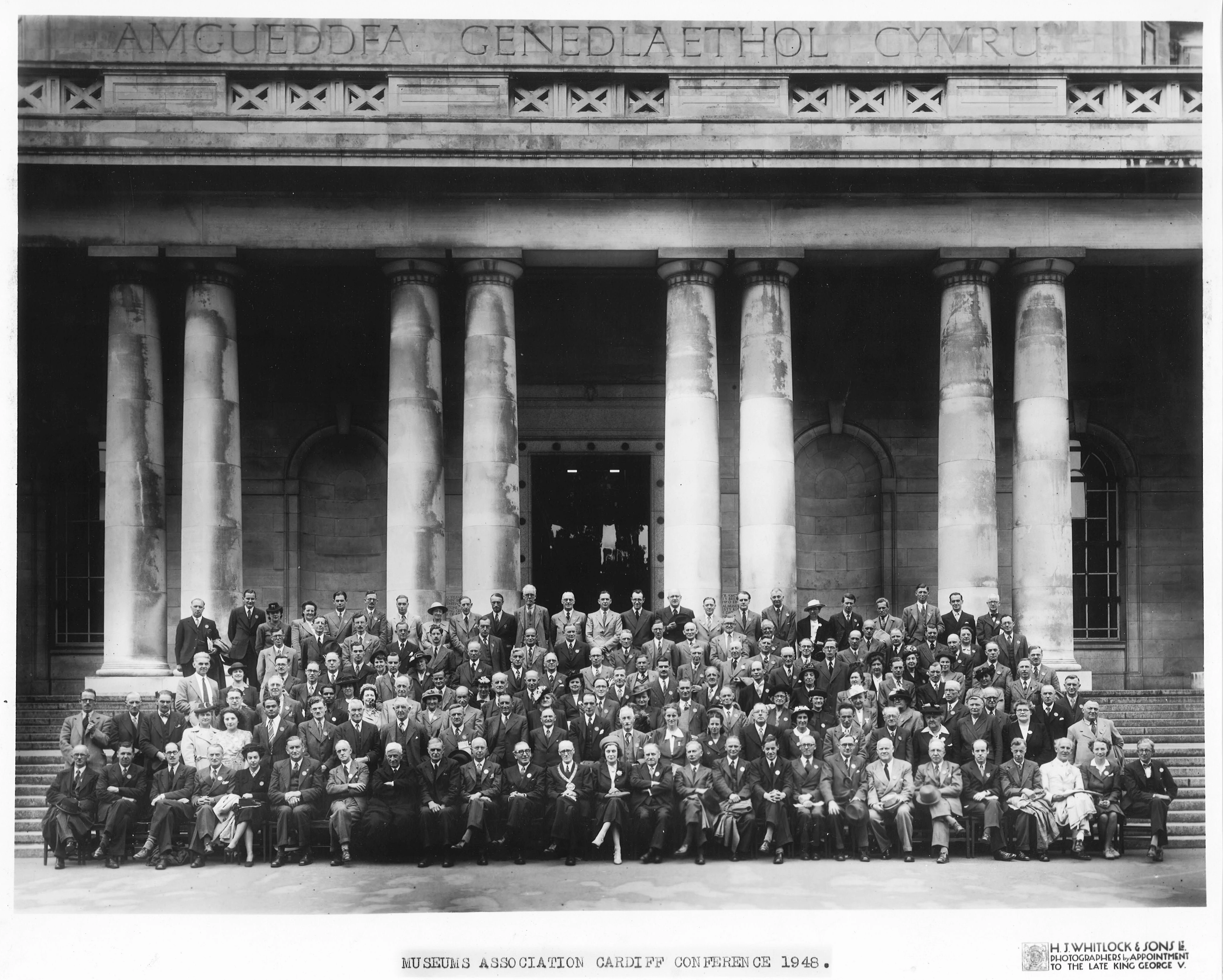

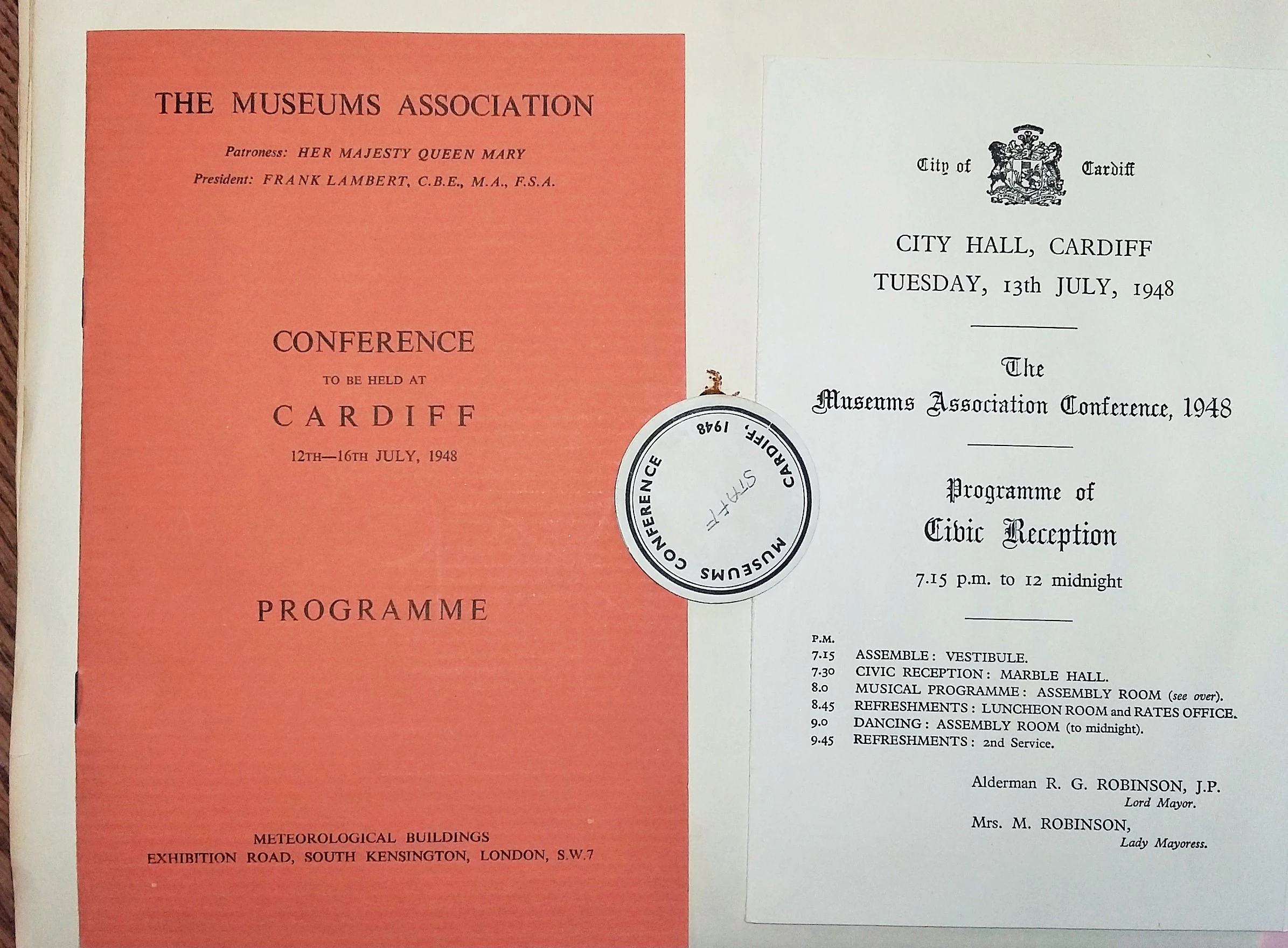

![Museum Association Conference ephemera [1948]](/media/44924/version-full/Museum-Association-Conference-ephemera-1948-.webp)