Dyddiadur Kate: Dogni bara

, 22 July 2016

Gan gofio bod llai na blwyddyn ers diwedd yr Ail Ryfel Byd prin iawn yw’r sylw a gawn gan Kate Rowlands o ran sgil effaith y rhyfel ar ei theulu a’i chymuned. Dydi hynny ddim yn syndod i’r rheiny ohonoch ddilynodd ei hanes ym 1914 – wrth ei ddarllen, digon hawdd oedd anghofio fod cysgod y Rhyfel Mawr ar drigolion y Sarnau.

Fodd bynnag, sawl un ohonoch sylwodd ar ei chofnod y ddoe?

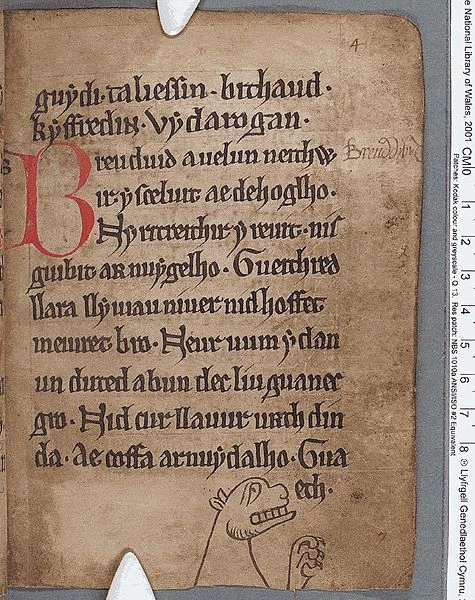

21 Gorffennaf 1946 - Adref trwy'r dydd. Dewi Jones (Tai mawr) yn pregethu yn Rhydywernen. Dechreu Rations ar y bara.

Ar drothwy’r Ail Ryfel Byd roedd Prydain yn mewnforio 60% o’i bwyd. Wrth gofio am y prinder yn ystod y Rhyfel Byd Cyntaf, cyflwynodd y llywodraeth y sustem dogni ym mis Ionawr 1940. Dosbarthwyd llyfrau dogni i bawb a bu’n rhaid i bob cartref gofrestru gyda chigydd, groser a dyn llefrith lleol. Roedd y rhain yn derbyn digon o fwyd ar gyfer eu cwsmeriaid cofrestredig. Y bwydydd cyntaf i gael eu dogni oedd menyn, siwgr a ham. Ymhen amser cafodd mwy o fwydydd eu hychwanegu at y sustem, ac fe amrywiai swm y dogn o fis i fis wrth i’r cyflenwad o fwydydd amrywio. Dyma enghraifft o ddogn wythnos un oedolyn:

Bacwn a ham 4 owns

Menyn 2 owns

Caws 2 owns (weithiau caniatawyd 4 neu 8 owns)

Margarin 4 owns

Olew coginio 4 owns (ond yn aml cyn lleied â 2 owns)

Llefrith 3 peint (weithiau dim ond 2 beint, ond caniatawyd

paced o lefrith powdwr bob 4 wythnos)

Siwgr 8 owns

Jam 1lb bob 2 fis

Te 2 owns

Wyau 1 wy yr wythnos os oeddynt ar gael

Wy powdr paced bob 4 wythnos

O fis Rhagfyr 1940 roedd popeth arall gwerth eu cael ar y sustem ‘pwyntiau’. Cai pob person 16 pwynt y mis i brynu detholiad o fwydydd fel bisgedi, bwyd tun a ffrwythau sych, gyda’r gwerth y nwyddau’n codi yn dibynnu ar eu hargaeledd.

Roedd hi’n dipyn o dasg gwneud i’r dognau bara’ tan ddiwedd yr wythnos, ac roedd yr ymgyrch ‘Dig for Victory’ yn annog y boblogaeth i balu eu gwelyau blodau a’u troi nhw’n erddi llysiau. Cafodd pawb eu hannog i gadw ieir, cwningod, geifr a moch - rhywbeth oedd yn ail-natur mewn cymuned wledig fel y Sarnau. Efallai nad oedd siopau lleol Kate wastad yn gallu cael gafael ar y danteithion megis y bisgedi, y bwydydd tun neu bysgod ffres o’r môr fel siopau’r trefi a’r dinasoedd, ond roedd manteision i fyw yn y wlad a’r wybodaeth gynhenid o fyw ar y tir. Doedd dim angen cwponau na phwyntiau i hela cwningod gwyllt, colomennod, brain a physgod dŵr croyw. Byddai’r plant yn cael eu gyrru i gasglu ffrwythau gwyllt a fyddai'n cael eu defnyddio i greu cacenni a phwdinau blasus, yn jamiau a jeli. Byddent yn casglu cnau cyll, cnau ffawydd a chnau castan, madarch, dail danadl poethion a dant y llew – ac mae’r arfer hwn o fynd i chwilota am fwyd gwyllt wedi dod yn arfer ffasiynol unwaith eto i’n cenhedlaeth ni.

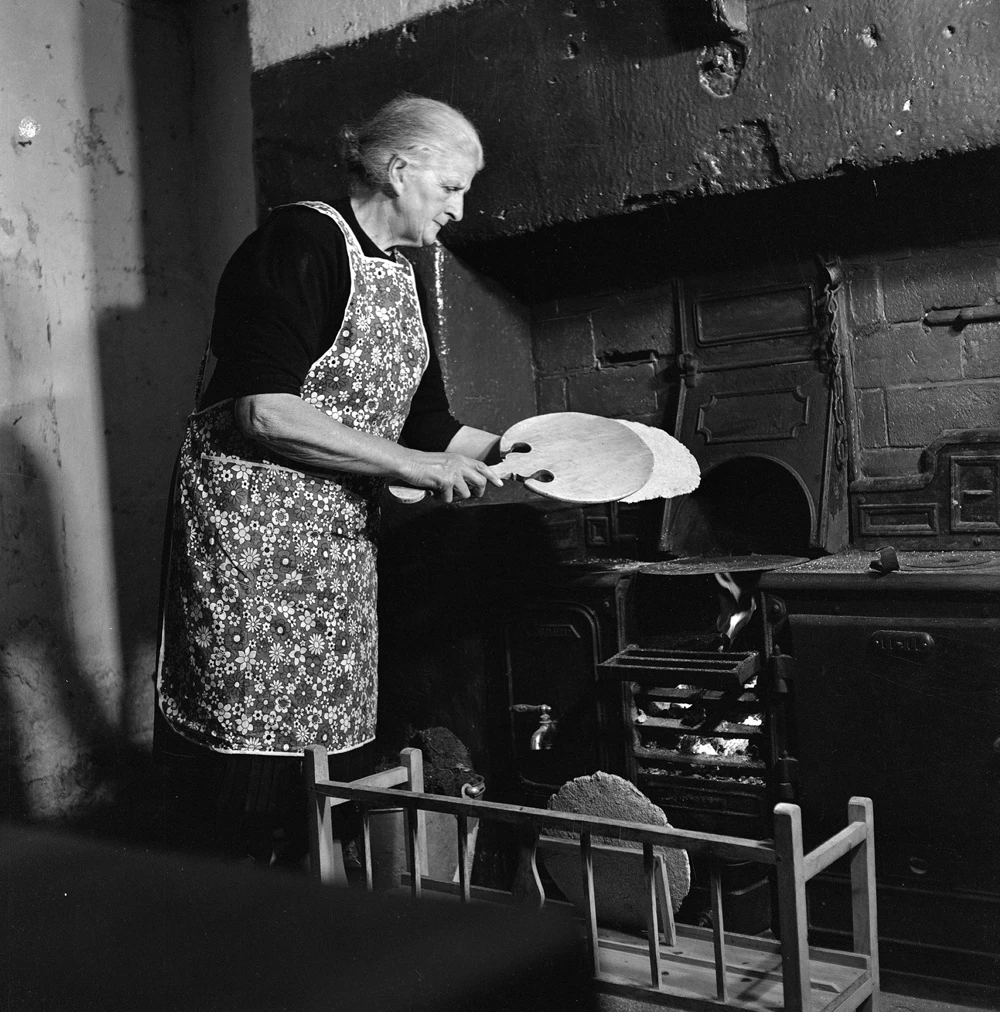

Gwaethygu gwnaeth y sefyllfa bwyd ar ddiwedd y rhyfel. Yn dilyn cyfnod sych a chynhaeaf gwael, bu’n rhaid dogni bara ar y 21ain o Orffennaf 1946. Roedd hwn yn benderfyniad dadleuol a gythruddodd y boblogaeth – nid oedd bara wedi cael ei ddogni yn ystod y rhyfel. Ysgwn i faint o wahaniaeth gafodd hyn ar deulu Kate? Gwyddom ei bod yn parhau i bobi bara ceirch yn ystod 1946 – dyma oedd y bara a fwyteid fwyaf cyffredin yng Nghymru tan y bedwaredd ganrif ar bymtheg. Gwyliwch y ffilm hyfryd o’r archif yn dangos o Mrs Catrin Evans, Rhyd-y-bod, Cynllwyd, yn paratoi bara ceirch.

Daeth dogni bara i ben ar y 24ain o Orffennaf 1948, a chodwyd cyfyngiadau ar de ym 1952 – rhyddhad mawr i genedl o yfwyr te! Tynnwyd hufen, wyau, siwgr a da-das neu fferins oddi ar y sustem ym 1953 a menyn, caws ac olew coginio ym 1954. Daeth 14 mlynedd o ddogni i ben ar y 4ydd o Orffennaf 1954 pan godwyd y cyfyngiadau ar gig a bacwn. Mae hi’n anodd amgyffred y rhyddhad a deimlwyd, yn arbennig o ystyried yr ystod eang o fwydydd a danteithion sydd ar gael i ni heddiw.