Our Plants Are Flowering

, 29 March 2023

Spring has arrived Bulb Buddies,

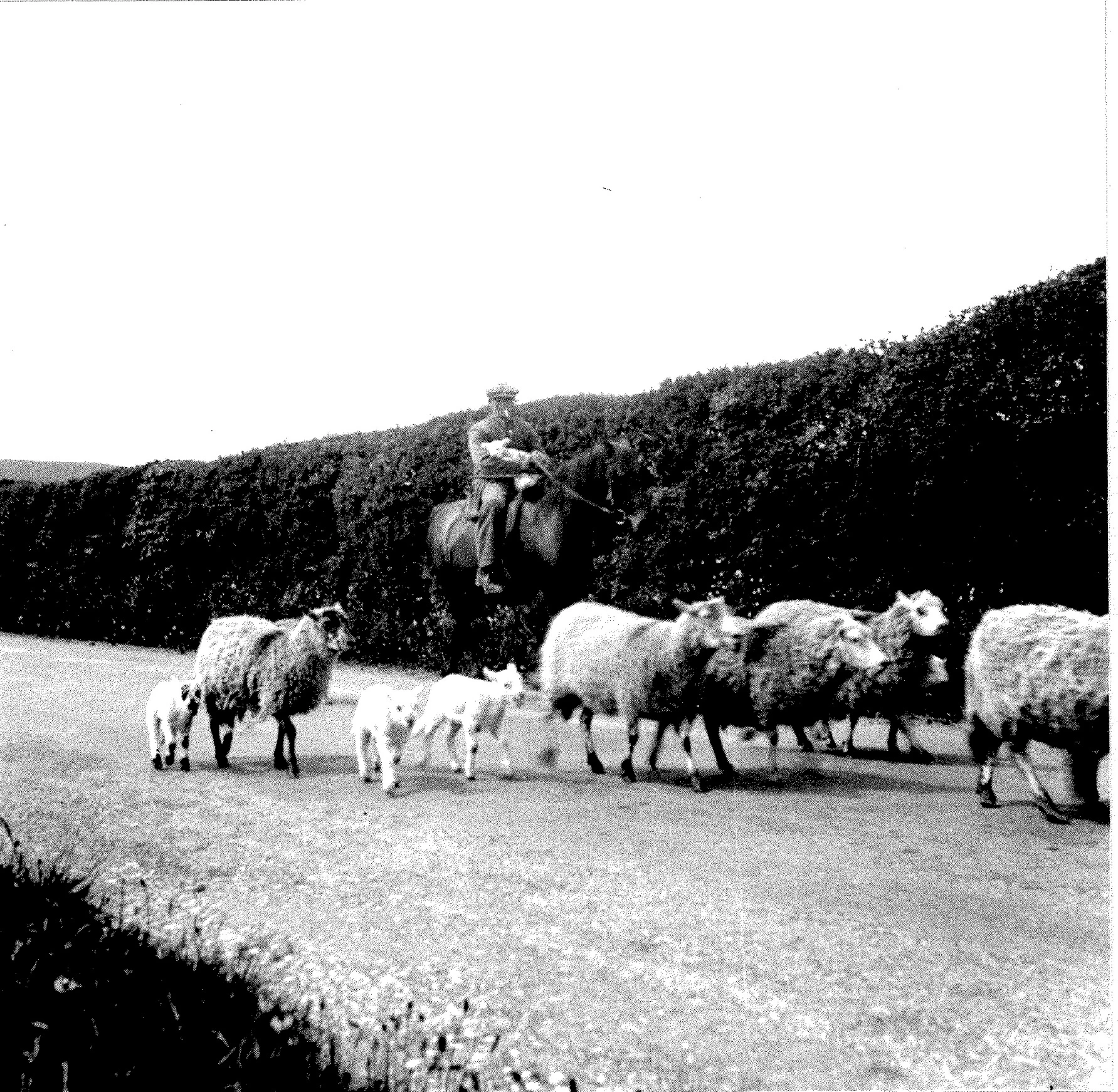

I’m sure we’ve all noticed signs of spring, including crocus and daffodil plants in full bloom! Have you ever wondered why these plants flower, and how to tell when they have flowered? Let's explore this together.

Daffodils and crocuses are both bulb plants, which means that they grow from bulbs that are planted in the ground. These bulbs store energy for the plant to use when it's ready to grow. The bulbs stay dormant through most of the winter and begin to grow as the weather warms, which is when their shoots first emerge from the soil. Shoots appear first, so that the leaves can produce food for the plant through photosynthesis, where energy from sunlight is used to turn carbon dioxide and water into sugar and oxygen. The plants use the sugar as food, to provide energy to continue growing and to replenish their bulb ready for the following winter. As the plants continue to grow, they produce leaves, stems, and flowers.

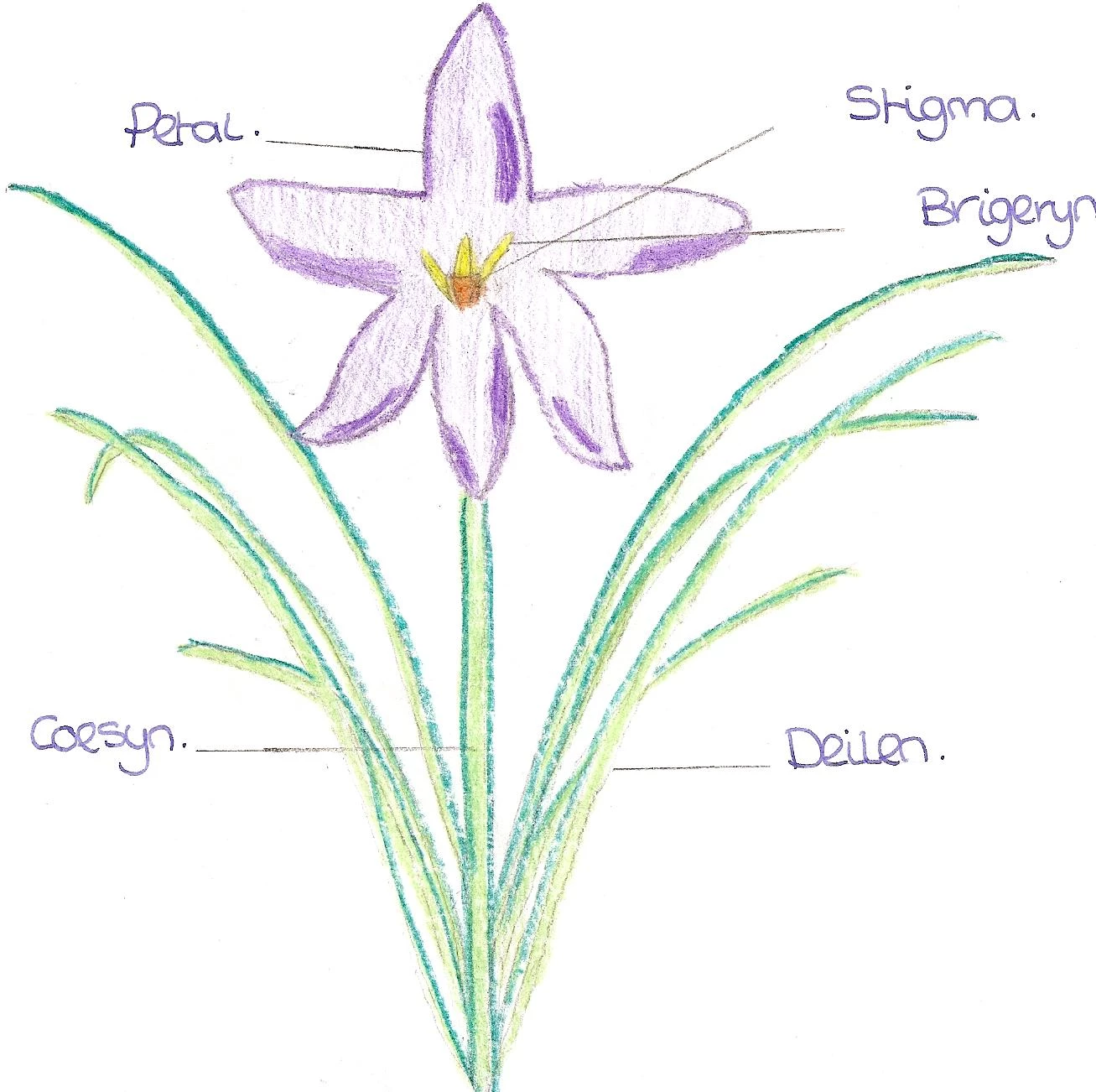

You can tell when these plants have flowered by looking for the blossoms on the stem. Daffodils usually have one yellow or white trumpet-shaped flower on a long stem, while crocuses have smaller, cup-shaped flowers that come in a variety of colours like purple, white, and yellow. These bright, colourful flowers attract pollinating insects like bees and butterflies. Pollen is sticky, so it attaches to pollinating insects and is taken by them to different flowers. Pollination happens when pollen from the male part of a flower (the stamen) is transferred to the female part of a flower (the pistil). Once this happens, the flower can produce seeds.

After the flowers have bloomed and the seeds have been produced, the plants start to die back. Our little bulbs will then go dormant again, until the next growing season.

Some schools have shared that their plants have flowered. You can see which schools have sent in flowering records by looking at the project map and the flower graphs. Remember, you can also look at results from previous years to compare. Why not have a look to see if your school has taken part in the project before?

I’ve attached the Keeping Flower Records resource to the right of the page. This looks at how to take height measurements for your plants and how to tell when the flower has fully opened. It also lists some resources on the website, like the activity sheets for naming parts of plants.

We ask that you note the date that your plant first flowers and the height of your plant on that date to your flowering chart. You can then upload this information to the website when next entering your weather data. Remember, we ask for measurements in mm. If you accidentally record your height in cm it will show on the website in mm. This means that a 15cm daffodil becomes a 15mm (1.5cm) daffodil!

I’ve attached some botanical illustrations we’ve been sent by schools in previous years. Why not make a study of your plants and draw what you see? It can be interesting to make regular drawings of your plants, to see how they change over time.

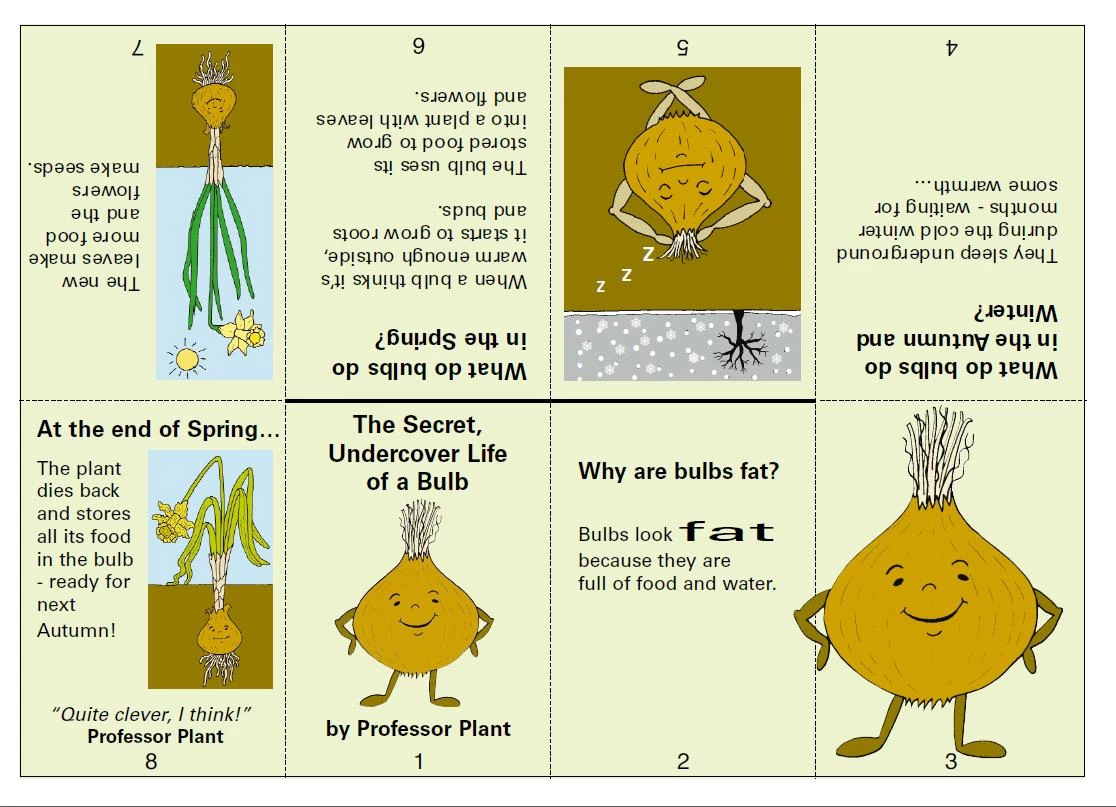

We’ve watched our plants from bulb to flower. I have seen from the comments that many of you have been fascinated by the changes you’ve seen. I’ve attached an activity sheet for creating an Origami booklet that explores the life of a bulb. There is a version that you can colour in yourself and a version that is already in colour.

We are in the last week of weather data collection. We ask that schools upload all of their weather data to the website by 31 March. If your plants have flowered, please upload your flowering data by 31 March. If your plants have not yet flowered, please let us know in the comments. There is further guidance around this in the attached ‘Keeping Flower Records’ resource.

Please share photos with us by email or Twitter, it’s always lovely to see the plants in bloom. Please share your thoughts on the project in the comments section when uploading your data, you could also let us know what you think the mystery bulbs were this year!

Keep up the good work Bulb Buddies,

Professor Plant & Baby Bulb