In 2020 Amgueddfa Cymru and Cruse Bereavement Support Cymru came together to support people across the country through their grief and create a lasting memorial full of memories to those lost during the time of Covid-19. It involved creating a square patch containing a memory of a loved one, in which ever way people chose, in whatever words or images they liked. Each patch created demonstrated a visual display of lasting memories of someone they loved who had died, created in unprecedented times. 50+ patches were sent to the Museum and have been carefully sewn together to form a Patchwork of Memories.

For the last two year we have all lived very different lives, with change to our normal the only constant. Losing a loved one is always hard but usually we have the comfort of others and collective mourning at funerals to help us say goodbye and share our memories. However, a death in the last two years has meant many of us being cut off from our support networks and our rituals or remembrance being altered.

Rhiannon Thomas, previous Learning Manager at St Fagans said about this project “Helping people with grief is something that I am personally passionate about. Having worked with Cruse Bereavement Support previously to support families I felt the Museum was able to help families dealing with loss in a different way. Amgueddfa Cymru and Cruse Bereavement Support Wales came together to create a project based around creativity and memory, the aim being to make a lasting memorial to those who have died during the pandemic.”

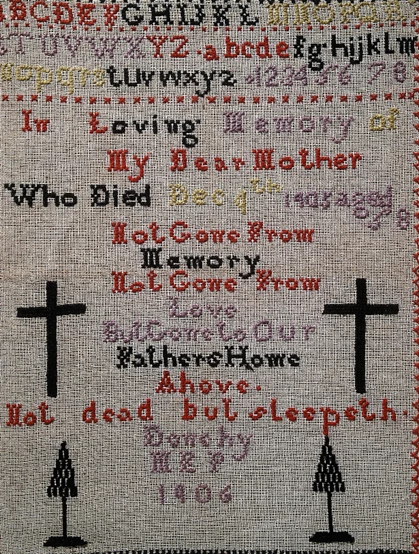

Creating something is not a new response to grief, there are several Embroidery samplers in Amgueddfa Cymru’s collections made in memory of loved ones or marking their passing. This sampler by M.E. Powell was created in 1906 in memory of her mother. Creativity during difficult times of our lives can help all of us to express deep held emotions that we do not always have the ability to put into words.

Bereavement Support Days

Alongside the Patchwork of Memories initiative, the Cruse / Museum Partnership also provide a safe inspirational space for the increasing numbers of children and young people awaiting bereavement support and help meet the diverse needs of bereaved children, young people and families who benefit from coming together to rationalise, explore and understand that they are not alone in their grief.

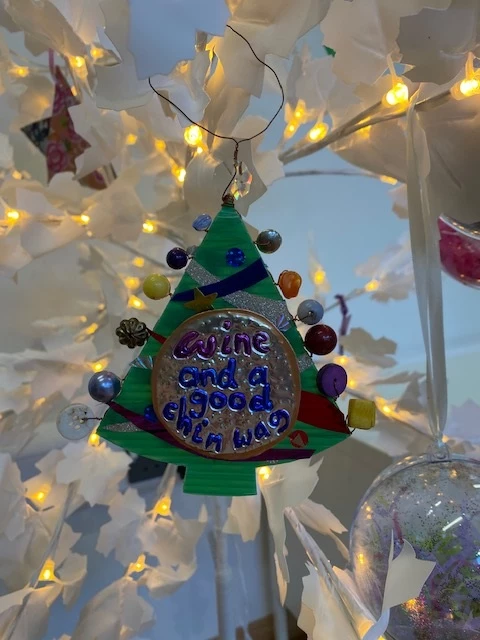

A series of quarterly Bereavement Support Days are held in partnership with St Fagans, for children, young people and their families experiencing grief and loss. There is specialist support from Cruse staff and volunteers along with art and craft activities provided by Head for Arts and immersive Virtual Reality experiences provided by PlayFrame, which are light-hearted, allowing people attending the chance to make and create things that can be taken home with them and or captured and stored into a virtual memory box. The activities available are designed to stimulate rather that prompt.

Here is the film created by PlayFrame on Ekeko, the virtual memory space they have been creating alongside this project, installing objects, memories and stories donated by participants into a virtual memory box for people to enter and explore:

https://youtu.be/KoQE00ff-rc

And a link the virtual reality memory space itself: https://www.oculus.com/experiences/quest/6371190072951353/

Alison Thomas, Cruse CYP Wales Lead said “Cruse Bereavement Support Wales provides in person support to children and young people within a variety of settings, so we see first-hand how difficult it can be for grieving children and young people. Their collective support on these days allows families the time and space to verbalise and begin to understand their loss and associated emotions. The focus of the Bereavement Support days is around children and young people, however, the benefits resonate through the whole family including the adults in attendance, some of whom require bereavement support on the day, most of whom stay for the duration and share a cuppa and chat with other bereaved parents and guardians. Following the session, the whole family can have a look around the Museum and spend time together in a safe and nurturing setting.”

Here are some of the written (in their own handwriting) evaluation feedback quotes from children, young people and parents / guardians who have attended the Bereavement Days:

'I feel calmer, less worried. It was good being able to speak to people my age who understood what I'm going through.'

'I was very included in all the activities and was always involved in conversation. There was a calm atmosphere making it easier to speak to people there.'

'I was very welcomed and was immediately approached by a friendly face. It was very inviting and was easy to speak to people there.'

'HAPPY' ?

'Love ? happy'

'Thank you Diolch, Diolch ?'

A mother of one of the young people said 'I feel much better than I did.'

Another mother said 'All was lovely, made to feel welcome, everything we did was good and the girls enjoyed themselves.'

The two memory quilts will be competed by the end of August 2022, following which we will hold a final project event with Cruse Bereavement Support Wales on 25th September at St Fagans National Museum of History, where we will display the two quilts and invite both the contributors who sent squares and the participants from the Bereavement Support Days to attend, along with the public, to see the quilts and share their experiences of taking part in the process.

We look forward to seeing you there.