Meet Ming the clam – how do we know it is the oldest animal in the world?

, 4 March 2020

A slice though a tree trunk. Can you see all 88 lines?

Ocean Quahogs, called Arctica islandica by scientists, grow up to 13cm long and can reach great ages. One shell was aged at 507 years old and so was nicknamed Ming because it would have been born in 1499 during the Ming Dynasty in China.

But how do we know how old Ming is? A slice though a tree trunk. Can you see all 88 lines?

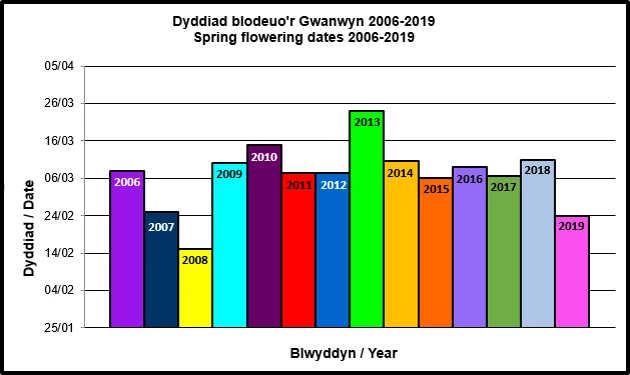

Trees, corals and clams grow by adding layers that create annual lines. Counting these lines allows them to be aged. This process of counting them is called Sclerochonology pronounced ‘sklero-kronologee’. Tree rings can be found by simply cutting through a tree trunk and the lines, visible as rings because tree trunks are roughly circular in cross-section, are clearly visible. In our Natural History gallery we have a large tree section with important events in history labelled on the rings – come and see it!

Coral polyps

A mushroom coral and a brain coral, cut to reveal the age lines

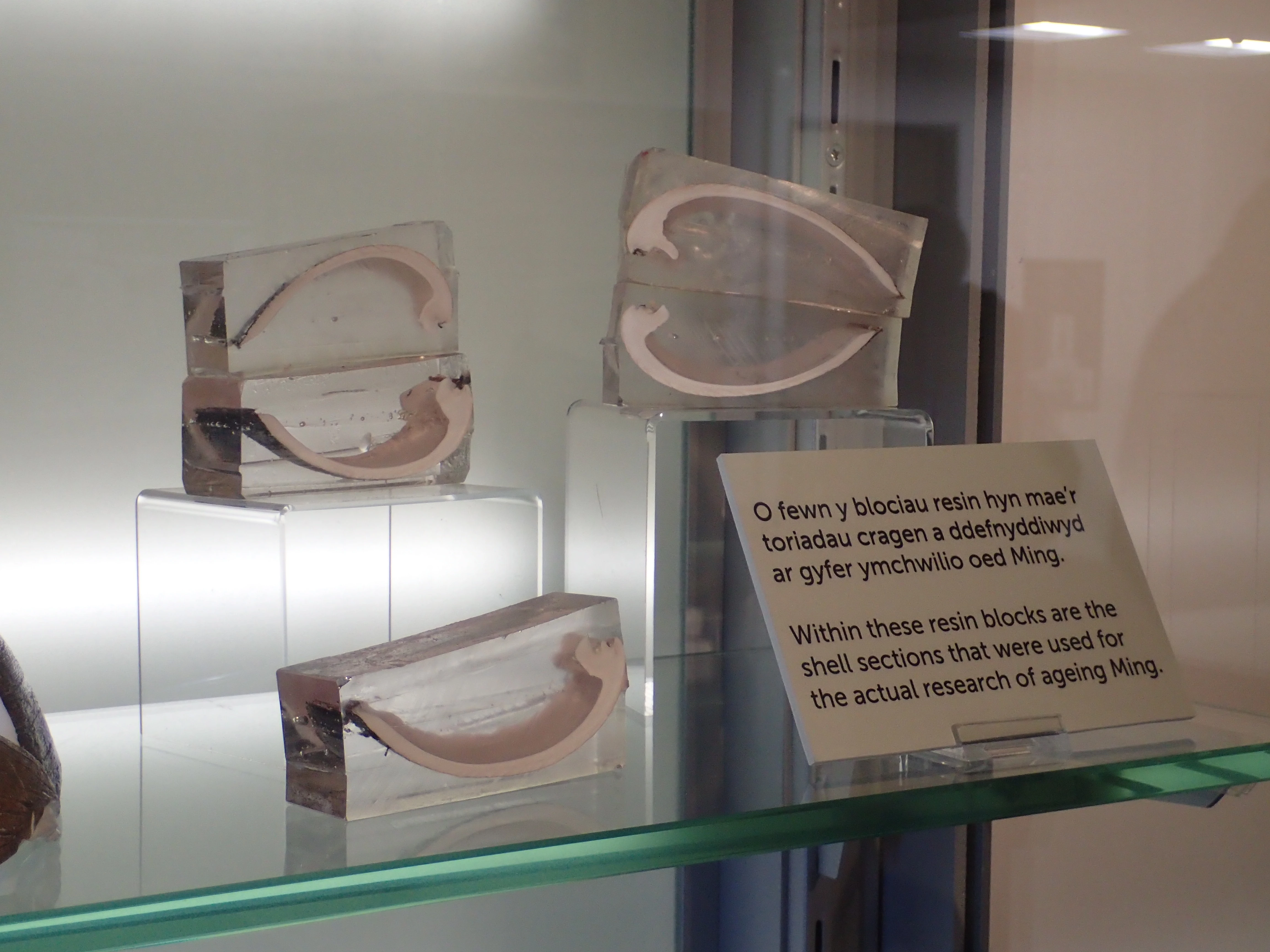

Enlarged models of shell sections

Ocean Quahogs lay down layers of calcium carbonate every year and these layers form lines that can be counted. The thin sections of shell need to be embedded in resin so they can be handled without breaking and the lines within can then be counted. As with corals, calcium carbonate is taken from the surrounding ocean to create layers of calcium carbonate and so Information on sea temperature, light and nutrient conditions is trapped in the layers. These characteristics can then be analysed decades or even centuries later to provide information on climate change. Scientists have already analysed over 1,300 years of past climate information from the North Atlantic. Resin blocks with thin shell sections inside

To find out where Ocean Quahogs live and how long some animals can live for go to:

https://museum.wales/blog/2020-02-12/Meet-Ming-the-clam---the-oldest-animal-in-the-world-/