DJ Jaffa's Slipmats

, 15 July 2025

Slipmats are an essential component for DJing when using vinyl. Even more so for Hip Hop DJs who also scratch or do 'turntablist’ tricks. Many, including Jaffa, found out early on that using the home hi-fi system to learn how to scratch might soon ruin your parents record collection. Rather than rubbing the vinyl against the rubber or plastic of the turntable, a slipmat allows you to move the record back and force gracefully without damage. For this reason alone it would make sense for us to include a pair of slipmats in the exhibition, but the fact that we have the first pair purchased by DJ Jaffa is a huge bonus for us.

If you’re not already engaged with the Hip Hop scene in Wales then you might not be familiar with the name, so here’s a little extra context for this particular item. As I go through some of Jaffa's history, it will relate to a few other pieces we have included in the exhibition. I’ll also explore more about the actual slipmats themselves.

Like many people in Wales and the rest of the UK, Jason Farrell, more widely known as Jaffa, first got a taste for Hip Hop after seeing the music video to Malcolm McLaren’s ‘Buffalo Gals’ which showcased graffiti, breaking, scratching and rapping from New York artists. He also remembers seeing snatches of the culture on the BBC 2 show ‘Entertainment USA’ in 1983.

It wasn’t the World Famous Supreme Team DJs that he tried to emulate from the video first though, it was the Rock Steady Crew breakers. He started practicing as often as he could, both at home and school, using any pictures or clips from the television that he could find. When the ‘breakdance’ craze hit its peak after films such as ‘Beat Street’ and ‘Breakdance The Movie’ in 1984 he was already advanced for the time and entered his first proper battle against a crew from Port Talbot in Cardiff city centre.

I don’t have the space to give you Jaffa’s whole history here, but this is integral to the next stage of his development because it was after battling a crew from Bristol that he became friendly with them all and started to spend his weekends hanging out across the bridge. He would go to Wild Bunch parties and witnessed the rise of the Bristol scene, noting how the future Massive Attack members approached the art of DJing.

But it was while hanging out at St Paul’s Carnival, watching his friend Dennis Murray performing turntable tricks on the Galaxy Affair sound system, that he realised he wanted to become a DJ himself. Dennis Murray incidentally would go on to become an important pioneer of the rave movement as DJ Easygroove.

The DJ at his local Whitchurch Youth Centre would occasionally allow him to play records and as I mentioned above, he developed a way to learn scratching on the home hi-fi system, using crude homemade slipmats made of cardboard. He had to learn mostly by ear, dissecting live audio recordings of the DMC Championships, where the world’s top turntablists would compete. However, when he got his first set of professional record decks in 1986 he was able to take his DJ skills to the next level.

Of course this meant buying a proper set of slipmats. He had already been purchasing records from the Spin-Offs record shop on Fulham Palace Road in Hammersmith, West London, mostly via mail order at the time. Spin-Offs was a shop opened by New York DJ Greg James, who had moved to London to help open The Embassy night club in 1978. Greg is widely credited as being the first DJ to bring the disco style of DJing - seamlessly mixing the records together - to the UK.

Spin-Offs was also known for selling the latest DJ equipment, so it was the perfect place to find the right slipmats. Jaffa remembers that it was DJ Richie Rich who served him that day. He was a well-respected DJ at the time with his own show on Kiss FM, back when it was a pirate radio station. He also had some underground Hip Hop and Hip House hits in the 80s and 90s and started the Gee Street record label.

I’m personally intrigued that these slipmats say Mixmaster on them. There would have only been a few DJs known for the name ‘Mixmaster’ at the time. Mix Master Mike had not yet joined the Beastie Boys or started his career. Mixmaster Spade was still only making underground tapes in Compton, California. The three that come to mind around 1986 would be: Mixmaster Morris with his Mongolian Hip Hop Show on London’s Network 21 pirate radio station; Mixmaster Ice of the New York group U.T.F.O; and Mixmaster Gee And The Turntable Orchestra from Long Beach who had a couple of underground hits on MCA Records. But I’m getting slightly off tangent here.

Jaffa locked himself in his room and practiced. Eventually he was coaxed out with his decks to set them up outside Rudi’s Donut store at the Capitol Centre end of Queen Street in Cardiff. Although there were some club DJs playing Hip Hop locally at the time, such as Paul Lyons in Lloyds, this is widely viewed as the first proper Hip Hop jam in the city. Jaffa brought along a microphone which was picked up by just one rapper from Gabalfa called Dike (pron. Dee-Kay).

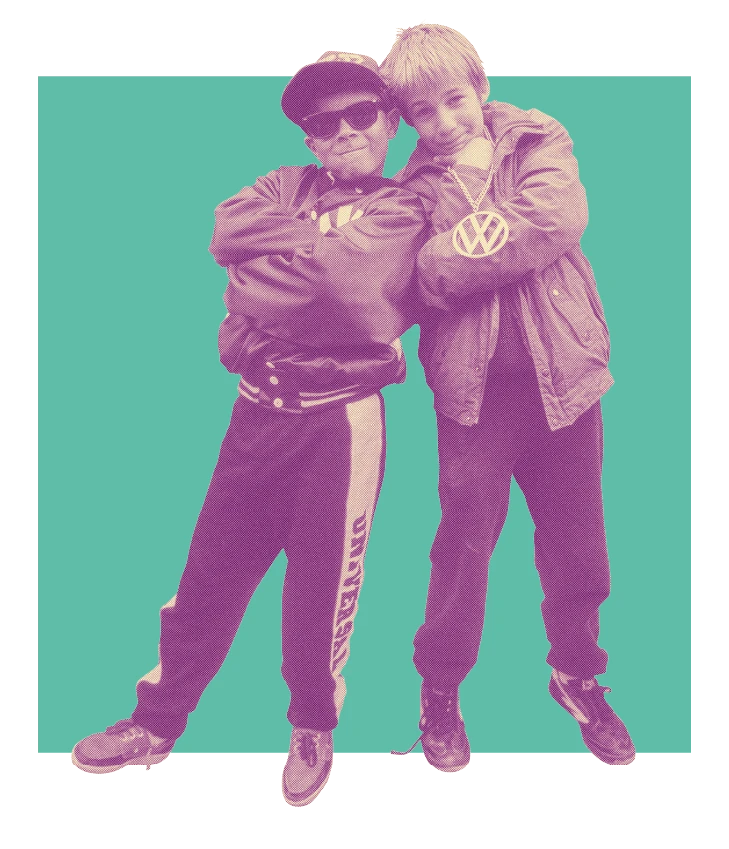

After that there were regular Saturday afternoon Hip Hop jams at Grassroots youth centre. Jaffa would DJ and rappers such as Dike, Mello Dee (later known as 4Dee) and MC Eric (later known as Me-One) would jump on the mic. A crew formed around them called Hardrock Concept, made up of rappers, graffiti artists and Jaffa. This was a period where collectives were more prominent than individuals, but towards the end of the 80s Jaffa and Eric would break off from the rest and move to London. A major label deal with Jive Records followed and their tracks featured on the compilations Def Reggae and Word Four under the name Just The Duce. These are both in the exhibition as well.

Jaffa eventually returned to Cardiff and Eric went on to global chart success with Technotronic. During the early 90s many people left Hip Hop behind when the rave scene exploded, but Jaffa helped to keep the culture going through his work alongside 4Dee and his sister Berta Williams (RIP) with The Underdogs – a youth organisation based in St Mellons that was focussed around developing skills such as Hip Hop dance, rapping and DJing. He has remained a cornerstone of the scene here ever since and has been involved in countless projects from Rounda Records to groups such as Tystion, Manchild, Erban Poets and Kidz With Toyz – right up to Xenith today.

He once deejayed for 70 hours, breaking the UK record for longest set, but just missing the World Record by 4 hours. He supported Snoop Dogg on his UK tour and he still DJs every weekend. He hosts the show This That & The Third on the Paris based station Radio Raptz, showcasing countless releases from Welsh artists. He has featured on various releases across the world as both a DJ and producer, including The Yellow Album from The Simpsons (his scratches are on the track ‘The Ten Commandments of Bart’ which Dike co-wrote the lyrics for).

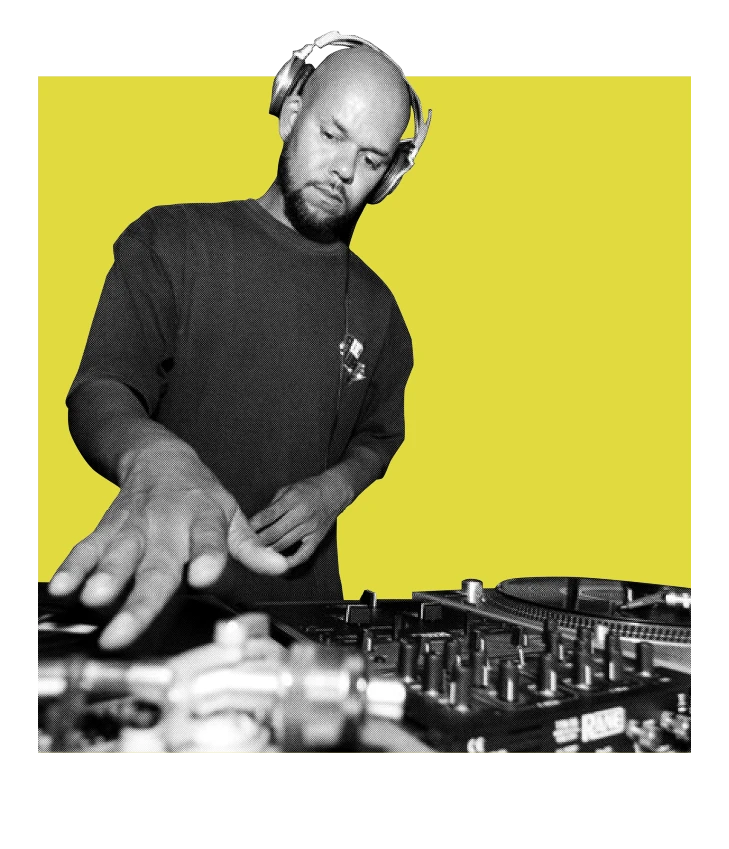

Jaffa has also been integral in putting this exhibition together and is the main face on our posters, so it seems fitting that we should focus on his slipmats here. Hopefully, now you can see why we are so excited to include them. Do revisit this blog as we look into other items you will find in Hip Hop: A Welsh Story.