Walking for Health at St Fagans

, 12 August 2016

This week we welcomed the lovely Croeso Club from Caerphilly to St Fagans. They are an informal community group set up by a local resident, Sandra Hardacre, almost ten years ago. The group aims to support community members to learn new skills, be sociable with others and go on new adventures.

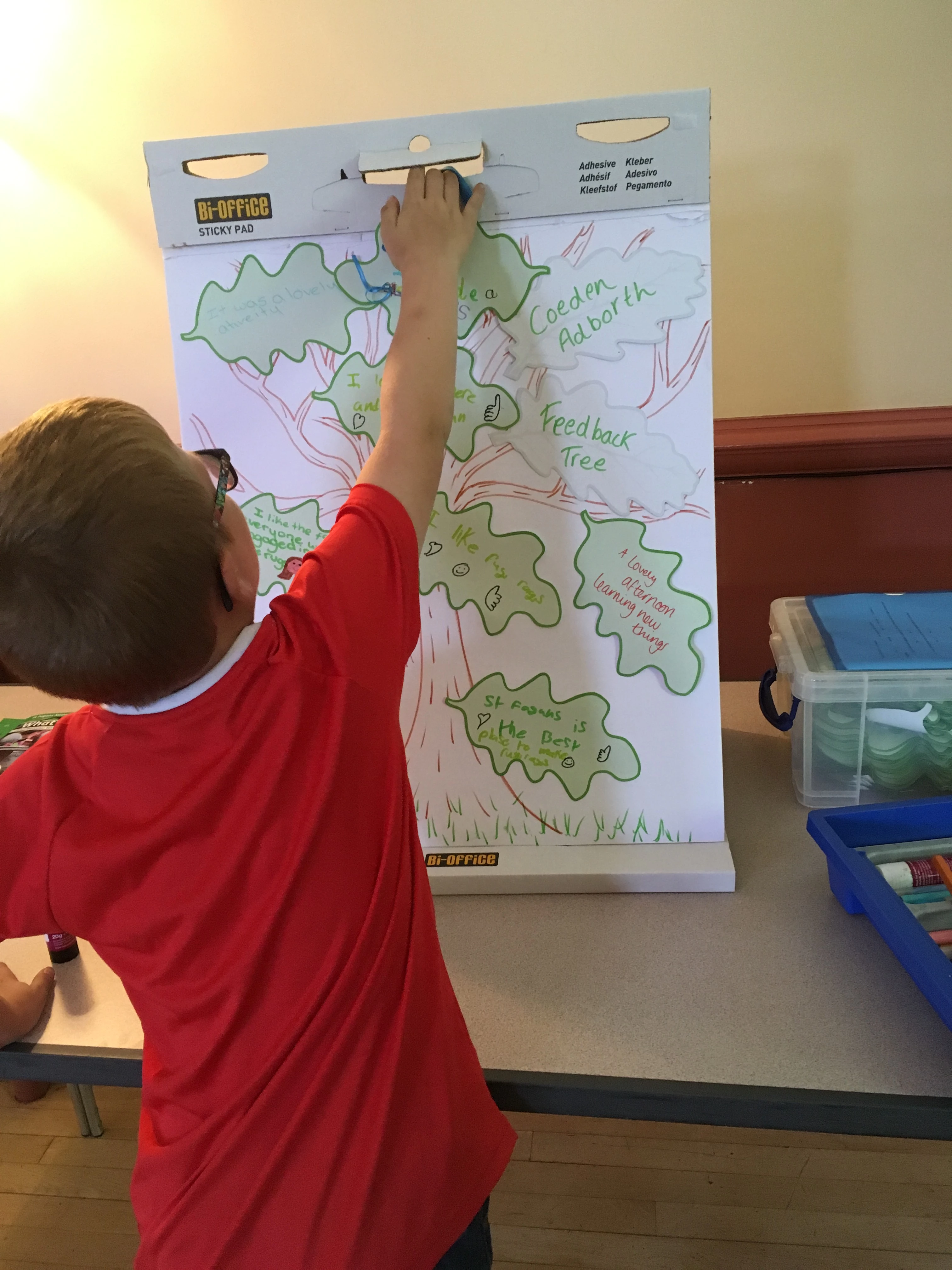

Over the last 6 weeks they have been working with Groundwork Cymru to help to pilot a new project called Go Green 4 Health, which is all about inspiring, supporting and encouraging individuals to use the outdoors to be more active. Each session focuses on a different aspect of using the outdoors for activity, such as ‘the benefits to being outdoors’, ‘overcoming barriers’ and ‘’staying safe’.

|

For their last walk the group members had asked if they could come to St Fagans, so Flik Walls, project coorindator, got in touch with us at the Museum and we set it up. We planned a 30 minute walk, taking in some of the key buildings at St Fagans such as Nant Wallter Cottage, Rhyd-y-Car Terrace Houses and the Oakdale Workmen's Institute, of which some of the ladies had very fond memories. We also made sure there was plenty of time to stop for a coffee and piece of cake on our way around. This was a perfect chance for the ladies to talk about their experiences of being part of the Go Green 4 Health project and share their thoughts and feedback with myself, the Groundwork Team and the project evaluator Katy Marrin. It was also a lovely opportunity for the group to share poems some of them had written about their journey together. Here's a lovely poem written by Lyn: Go Green 4 Health Poem Two lovely people came to coax us all to walk, To ramble and enjoy ourselves and also have a talk.

We played walking bingo, I’m sure it was a fix, Next we all said poems that was a real mix.

A lovely trip to Trelewis Park, fresh air and loads of rests, Caerphilly Castle we went next, soaked through right to our vests.

And what about walking football that we were meant to play, They said there was some cheating, ‘we were robbed’ I heard them say.

The last walk sadly to St Fagan’s, a fab day out for all, So now the Croeso Club love walking, they’ve really had a ball.

We are really looking forward to developing a link with Groundwork Cymru so we can continue to work together on similar projects in the future. Follow this blog for updates and to find out how it's all going. |