GRAFT March

, 11 April 2024

“March brings breezes, loud and shrill,

To stir the dancing daffodil.” Sara Coleridge, The Garden Year

March is Most Likely the Gardener's Busiest Month!

This month has consisted of sowing, sowing, and more sowing! We've sown different varieties of tomatoes, aubergines, runner beans, chilies, watermelons, salad leaves, herbs, and roots (to name a few!). Most have started life in propagators in the orange container (more on that later) or in the polytunnel, as most seedlings prefer a warm environment to germinate. Hardier seeds like spinach have been directly sown outside.

Move Over, Marvin Gaye!

Ani and Laurence expertly pruned the grapevine in the polytunnel. This is the time to cut back the vine to encourage new growth. Don't be afraid to cut back more than you think. The rule of thumb is to choose a few of the strongest canes to leave and prune the rest. Typically, people choose 10 to 12 good canes and shorten them to four or five buds each.

The Hügelkultur Method

We tried the Hügelkultur method with our raised beds alongside the glass panels of the colonnade. In Hügelkultur, you layer different organic materials together, which will slowly release nutrients into the soil for years to come. To try it yourself, simply add a base layer of cardboard, wood such as logs and smaller dried twigs, and hay or grass cuttings, followed by green organic material. Then layer a lot of compost and topsoil, and you're ready to plant. Please note that the soil level will fall as the layers decompose. In this case, simply add another layer of soil to the top.

Bye-Bye, Orange!

This month has seen us update one of the staples in the GRAFT garden: the orange container. Over the years, the vibrant orange container has, well, become a bit tired and showed its age. So we decided to give it a facelift and employed the expertise of brothers Hassan and Kareem, who designed and painted the container. It's turned some heads and really given the garden a new lease on life! The design reflects the important elements of the garden and connects to nature.

A Cockleshell Pathway

We took delivery of some Penclawdd cockles to build a cockleshell pathway, making the garden more accessible, especially on rainy days. This will be an ongoing project, so watch this space!

Natural Dyes Workshop

On Thursday, March 14th, GRAFT volunteers visited the National Wool Museum in Drefach to learn about natural dyes and how to incorporate them into the GRAFT garden.

Susan taught everyone about the natural dyeing process using different plants. Then, everyone had a go at dyeing wool themselves in various colors. They even gave GRAFT seeds to get started, which we plan to plant this month!

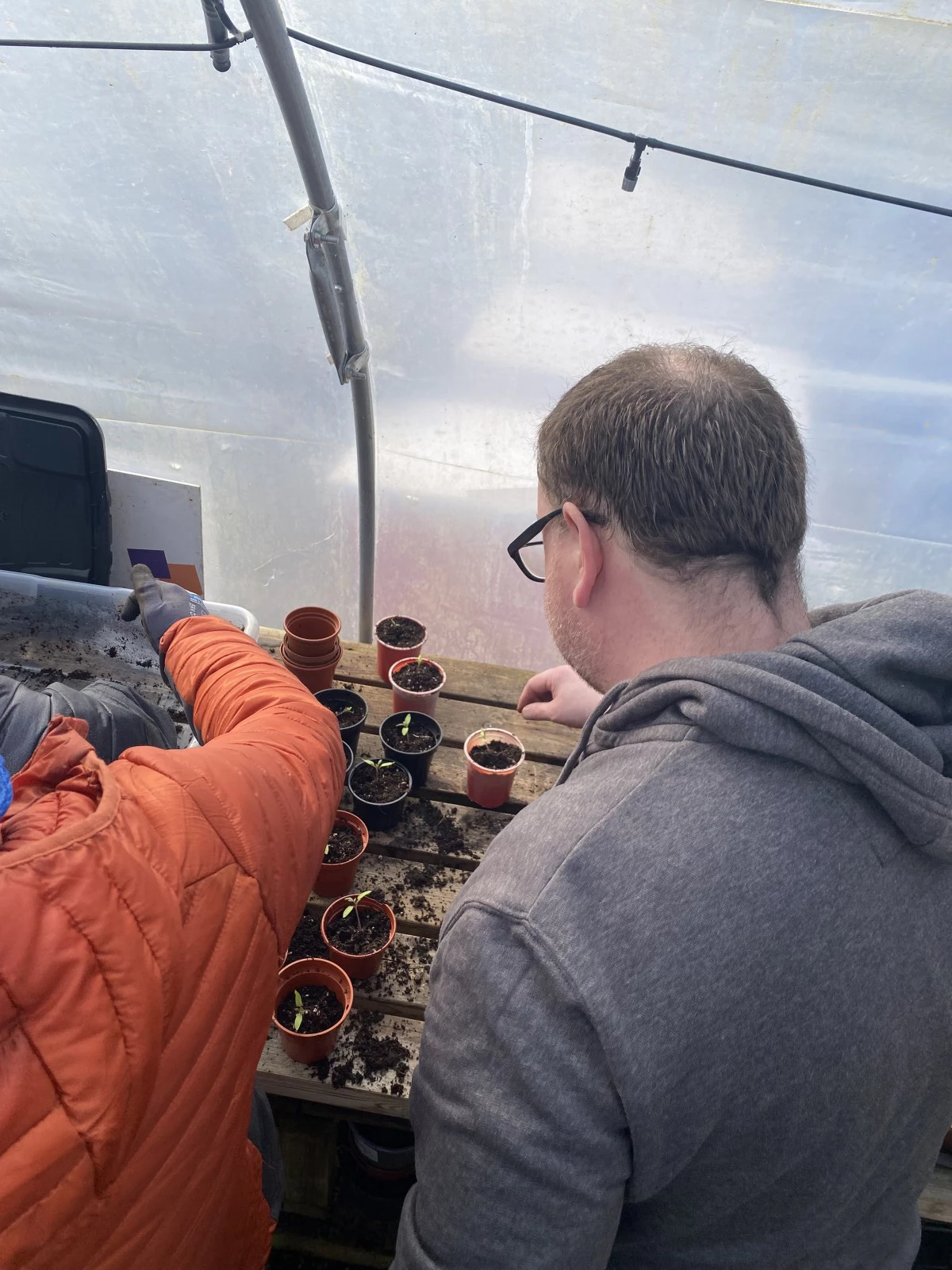

Chai and Chat Takeover

We are fortunate to be able to work with and host many community events and groups here at the Waterfront Museum! We're even more fortunate to offer them a taste of different aspects of the museum. On Wednesday, March 27th, the Chai and Chat group, which meets weekly at the museum, visited GRAFT and helped plant some seeds, transplant tomato seedlings, move strawberry plants, and harvest salad from our polytunnel. We're excited to welcome them back to the garden in the future!

Farewell, Zoë!

March also sees us sadly say farewell to one of the project founders, Zoë, who will be leaving the museum for new adventures! She leaves a great legacy in GRAFT and will be missed by all the volunteers, partners, and staff who use the garden.

I will be updating readers every month or two months with the general work we have done in the garden. We will pass on information we have learnt, things we have done well (and not so well) and any tips for budding gardeners (or experienced gardeners) out there to take to your own green space. I will also include a seasonal recipe from The Shared Plate using ingredients from GRAFT.