Flint in Egyptian Pharaonic Warfare

, 11 August 2015

This is the summary of a talk Carolyn Graves-Brown from Swansea's Egypt Centre gave at the recent "Heritage in Turbulent Times" event at National Museum Cardiff.

Studies of Bronze Age Egyptian weapons and warfare tend concentrate on metal weapons and ignore the part played by flint. Flint is not considered as attractive as copper or gold and in a milieu which is impressed by technological progress, metal is still considered superior. However, at least until the Early New Kingdom (c. the time of Tutankhamun or 1300 BC) there is strong evidence that flint weapons were standard military issue and far from being a primitive technology they were a natural choice for both utilitarian and ideological reasons.

Despite the fact that many hundreds of artefacts were found in a possible armoury in an Egyptian fort sited in Nubia (modern Sudan) and the fact that contemporary artefacts are known from sites in Egypt, flint found on Egyptian sites is often explained away as either foreign or intrusive to New Kingdom contexts. However, in many instances flint is a good choice for weapon manufacture, particularly where a quick and ‘dirty’ fight is envisaged. Flint is sharper, arguably cheaper and often more deadly than metal. Warfare and flint also had an ideological importance, it is the ideal weapon of the sun-god Re and perfect for destroying the enemies of Egypt. I concur that metal was a component of warfare, but make a plea for the role of lithics.

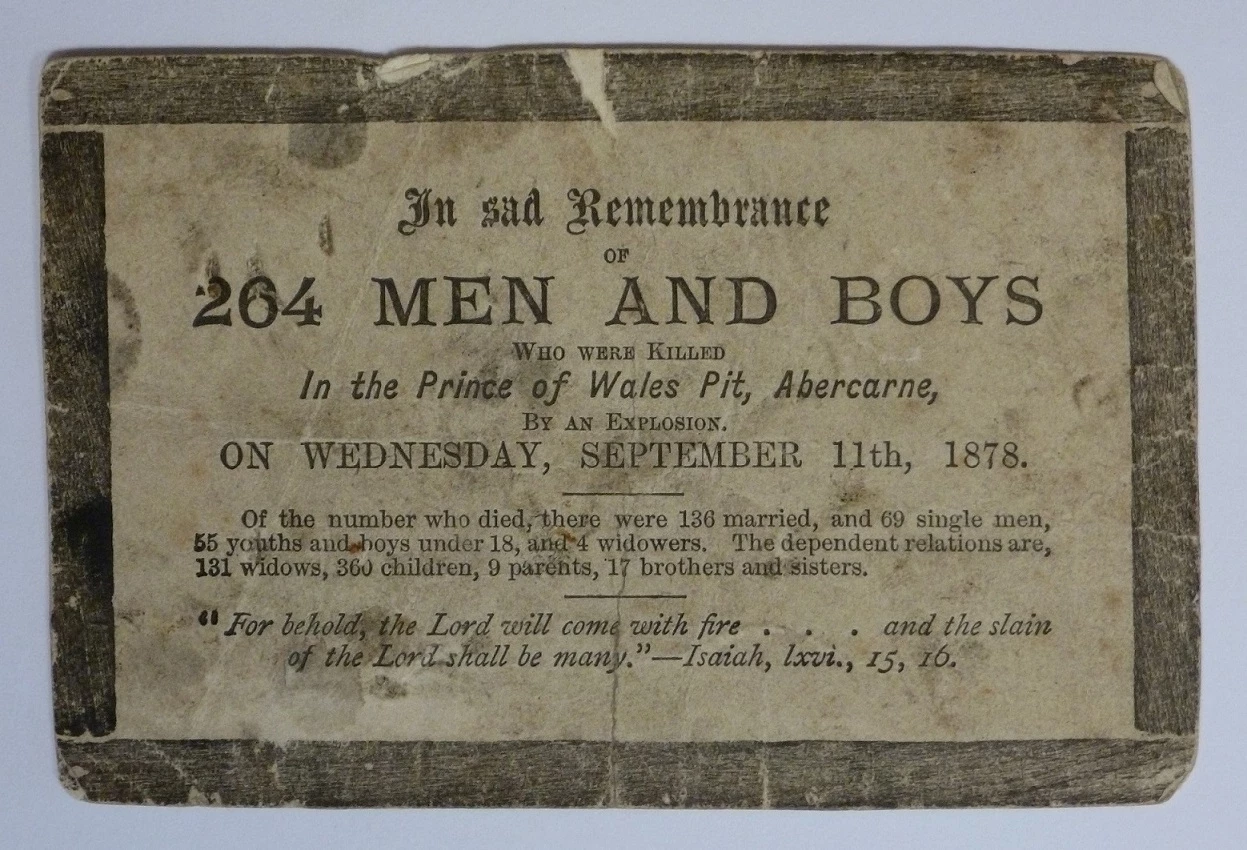

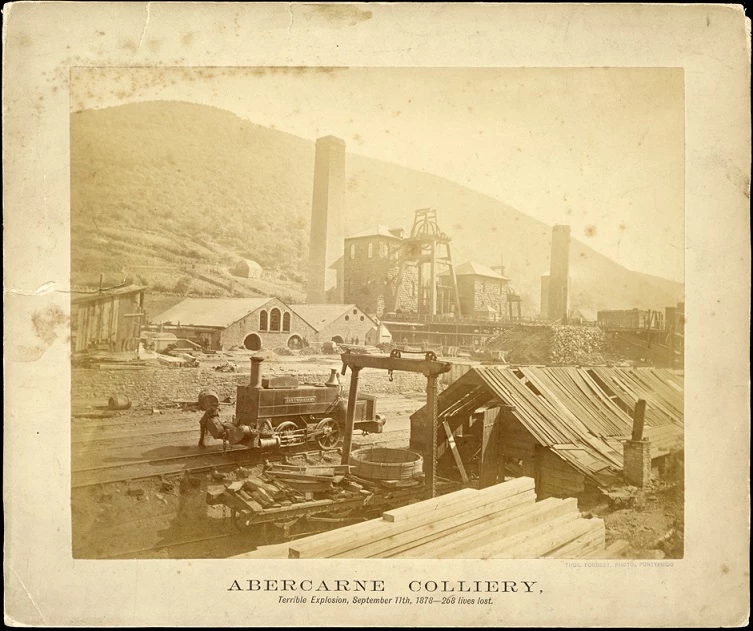

National Museum Wales and Cardiff University contribute to heritage preservation. If you would like to know more about "Heritage in Turbulent Times" please follow our blog.