First World War Catalogue Now Online

, 17 December 2014

After months of behind the scenes activity - rummaging in stores, researching, documenting, conserving and digitising - Amgueddfa Cymru's First World War catalogue is now online. At the moment, the catalogue includes over 500 records - archives, photographs and objects from the collections housed here at St Fagans. New records will be uploaded over the next few weeks, including some fantastic additions from the industry collections. We'll keep you posted.

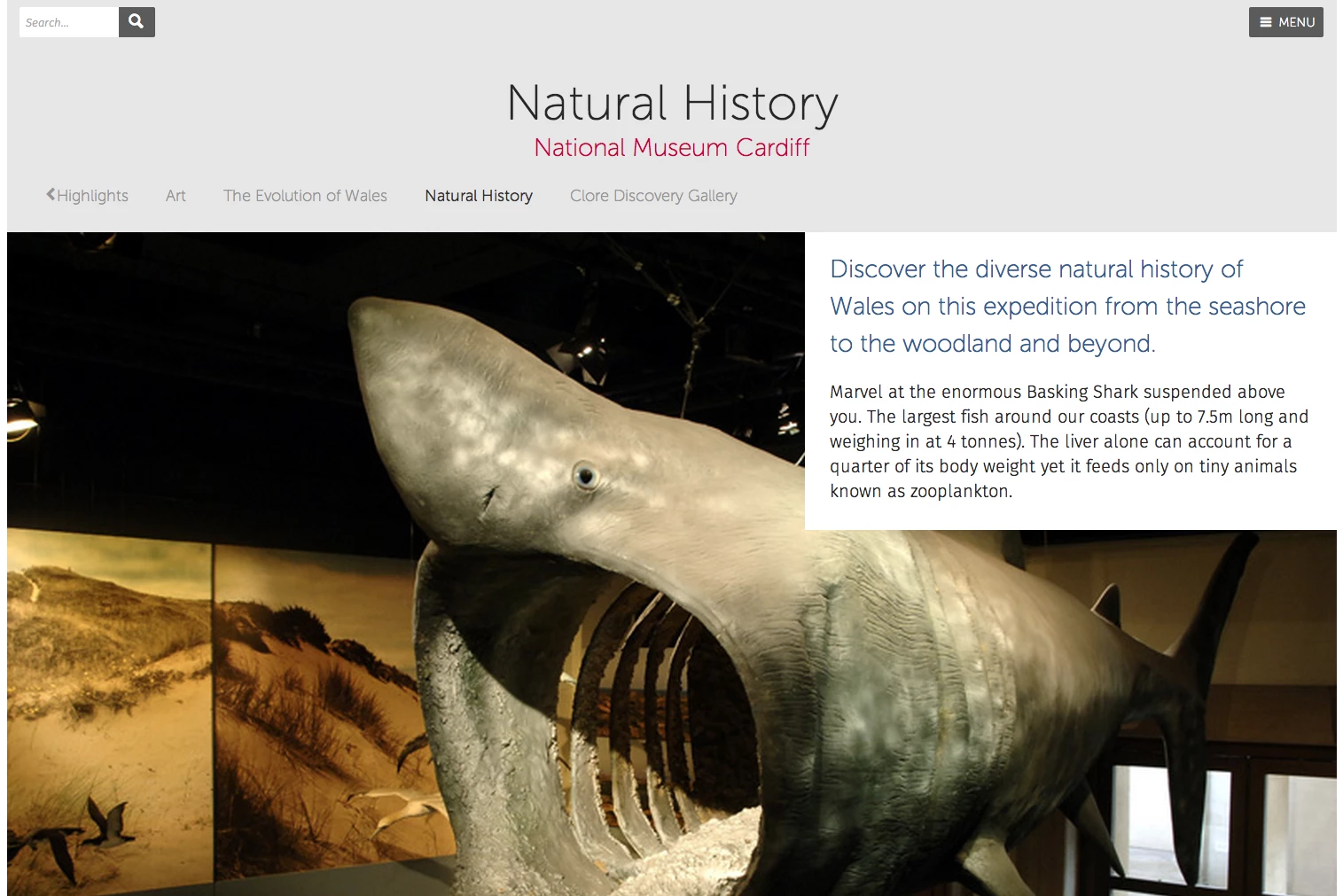

I can't tell you how much this project has meant to me and my colleagues. It may sound corny, but we really do feel emotionally connected to the people whose lives are commemorated in the collections. From Walter Stinson's delicate beadwork jewellery, to Brinley Rhys Edmunds and his typo-ridden memorial plaque, these stories have captured our imagination. To us, Walter and Brinley are no longer anonymous names on file.

Talking of files, it hasn't been easy to pull-together our First World War collections. When curators speak of "newly-discovered" or "hidden" objects, please don't think that museums are full of misplaced or lost items - there are no "dusty vaults" here! The issue is usually a lack of documentation - the information stored on file which helps us to locate and interpret the collections in our care. Collecting methodologies have changed over the years, so too standards in documentation.

Many objects featured in the database were originally catalogued according to their function, making it difficult for present-day curators to draw-out their First World War significance. A classic example being a set of prosthetic arm attachments used by John Williams of Penrhyncoch. These were found in the medical collections, catalogued in 1966 under "orthopaedic equipment". By chance, I was looking at the accession file a few months ago and found a scribbled note saying "wounded in one arm during WW1". If only the curator had asked more questions at the time, especially given that John Williams himself donated the arm attachments to the Museum!

Thankfully, accession files are never closed indefinitely. New research and the reassessment of collections through community partnerships means that we're constantly editing and tweaking our records. So, if you knew a John Williams from Penrhyncoch who lost an arm during the First World War, please do get in touch.

This project is supported by the Armed Forces Community Covenant Grant Scheme.

![Bronze memorial plaque, often known as the 'Dead Man's Penny'. Relief of Britannia holding a laurel wreath, surrounded by the inscription: 'HE DIED FOR FREEDOM AND HONOUR BRINDLEY [sic] RYHS [sic] EDMUNDS'](/media/33765/version-full/DF007322_01.webp)