Jessie Knight - The Lady Tattoo Artist

, 1 November 2023

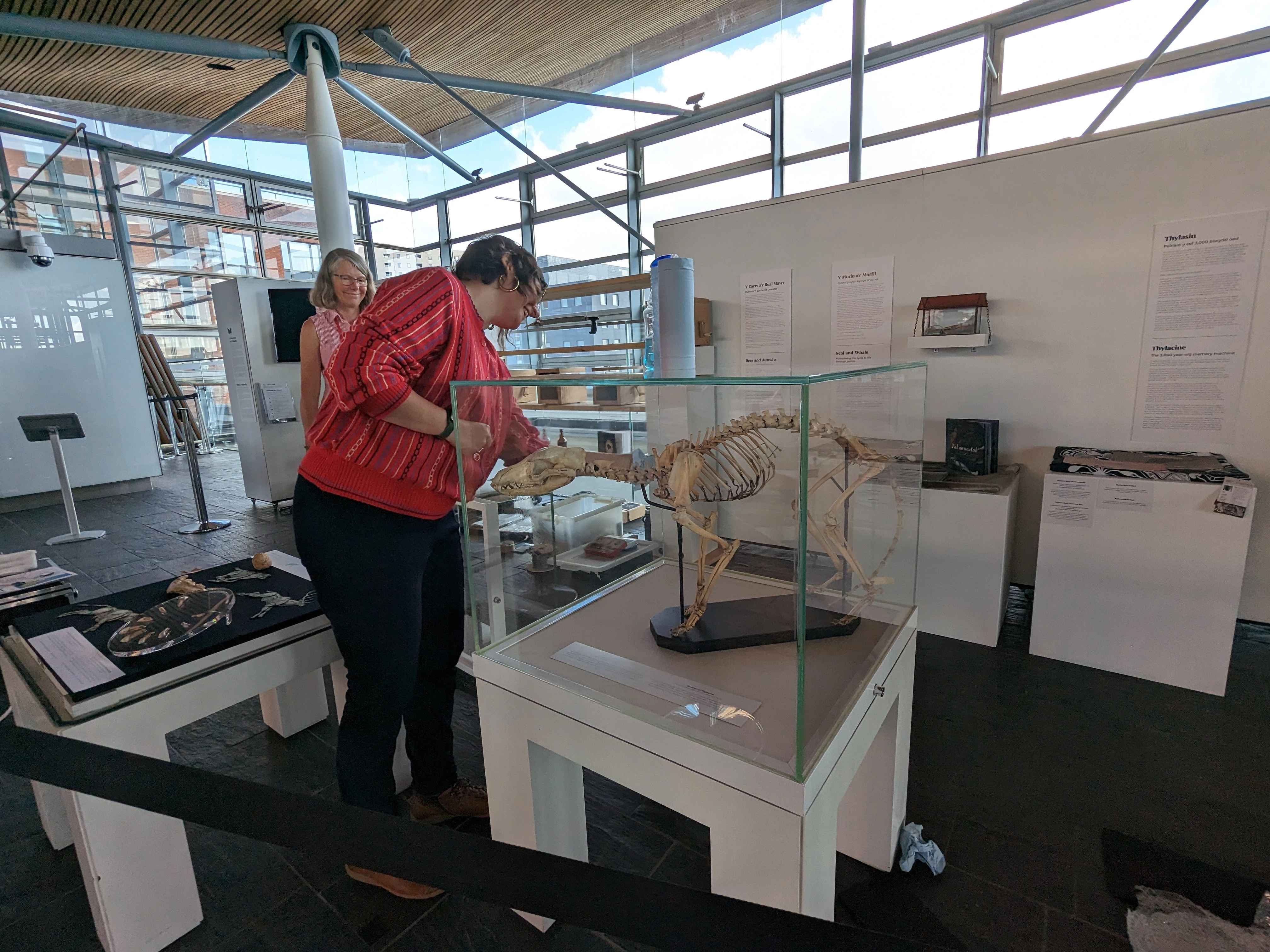

I was appointed an Honorary Research Fellow at Amgueddfa Cymru – Museum Wales earlier this year and I've finally made it down to see the collection I'll be working with!

I'm doing work on Jessie Knight, considered one of the UK's first female tattoo artists, and it was amazing seeing her machines, flash, art and photos. There are about 1000 items in the archive and I only looked at two boxes so I'm really excited to get stuck in and see what I can find. I'll be working with the collection for two years and am planning some community events as well as participatory research.

I got my first tattoo aged 19. A piece of flash chosen from the walls of a studio in Bath, inked on by a tattooist who I can’t remember anything about except he wore black gloves. Over twenty years later and I’ve got many more, mostly custom designs inked over multiple sessions, the latest by a woman whose mother I used to work with. Tattoos have, even since I got my first one, become more mainstream, more acceptable. And female tattoo artists are becoming more common - a far cry from the early 20th century when Jessie Knight began work.

Jessie, born in Croydon in 1904, is widely considered to be the UK’s first female tattoo artist. She began working at her father’s studio in Barry when she was 18, and after moving around the UK returned to Barry in the 1960s. After her death in 1992 her collection of photographs, artwork, tattoo machines and designs passed to her great nephew Neil Hopkin-Thomas and was acquired by Amgueddfa Cymru, with the help of art historian and tattoo academic Dr Matt Lodder, in 2023.

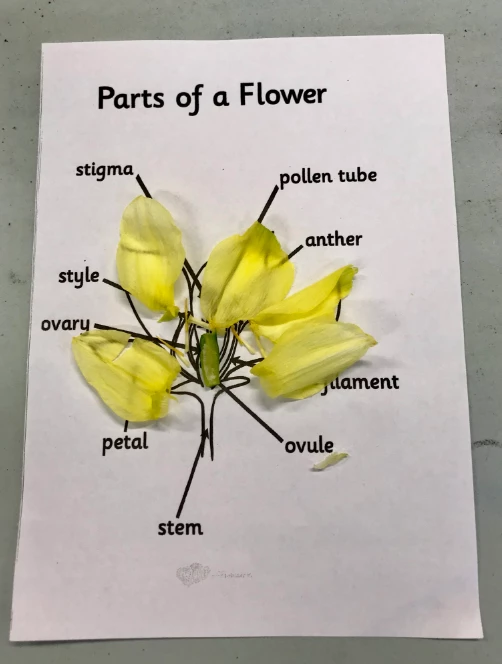

But why on earth should a tattooist’s archive be acquired by a museum, or put on display? As someone who has, and researches, tattoos the collection is a fascinating piece of subcultural history. And subcultures – like punk and hip-hop – have increasingly become the subject of exhibitions at museums and galleries. Tattoos reflect the hopes, loves and identities of the people who have them – as the tattoo of the highland fling that won Jessie second place in the 1955 Champion Tattoo Artist of All England competition attests – and give us an insight into the lives of people through the ages.

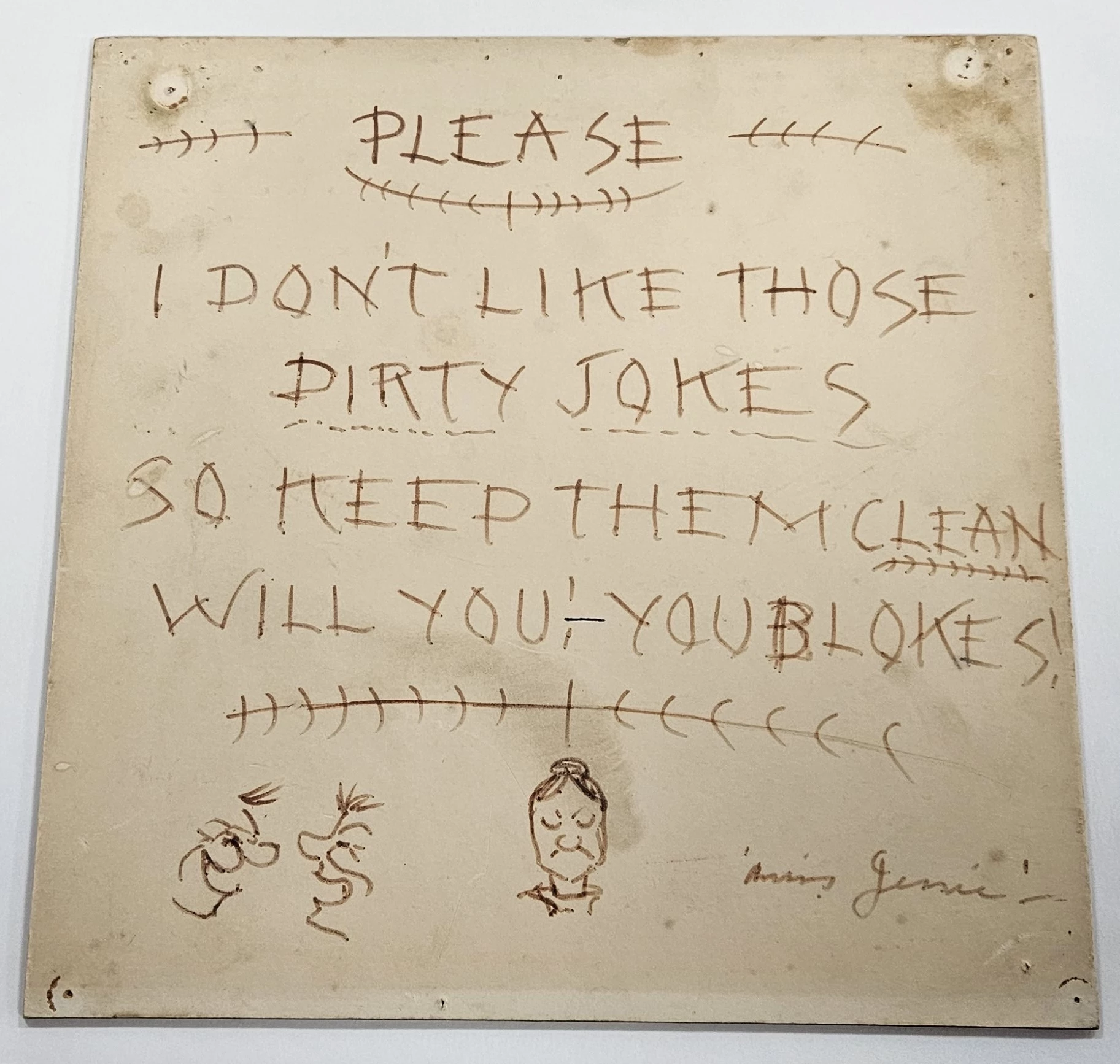

But the Knight collection also tells us about the cultural and societal norms of the time. It’s estimated that there were only five other female tattoos in the US and Europe working at the same time as Jessie. This was an incredibly tough industry for a woman and we can see some of the behaviour Jessie would have had to put up with in the signs she displayed – preserved within the collection. Her great-nephew has told stories about how Jessie’s shop was broken into and her designs taken, and how she would sit on a big trunk that held her designs while she was tattooing so no one could get to them.

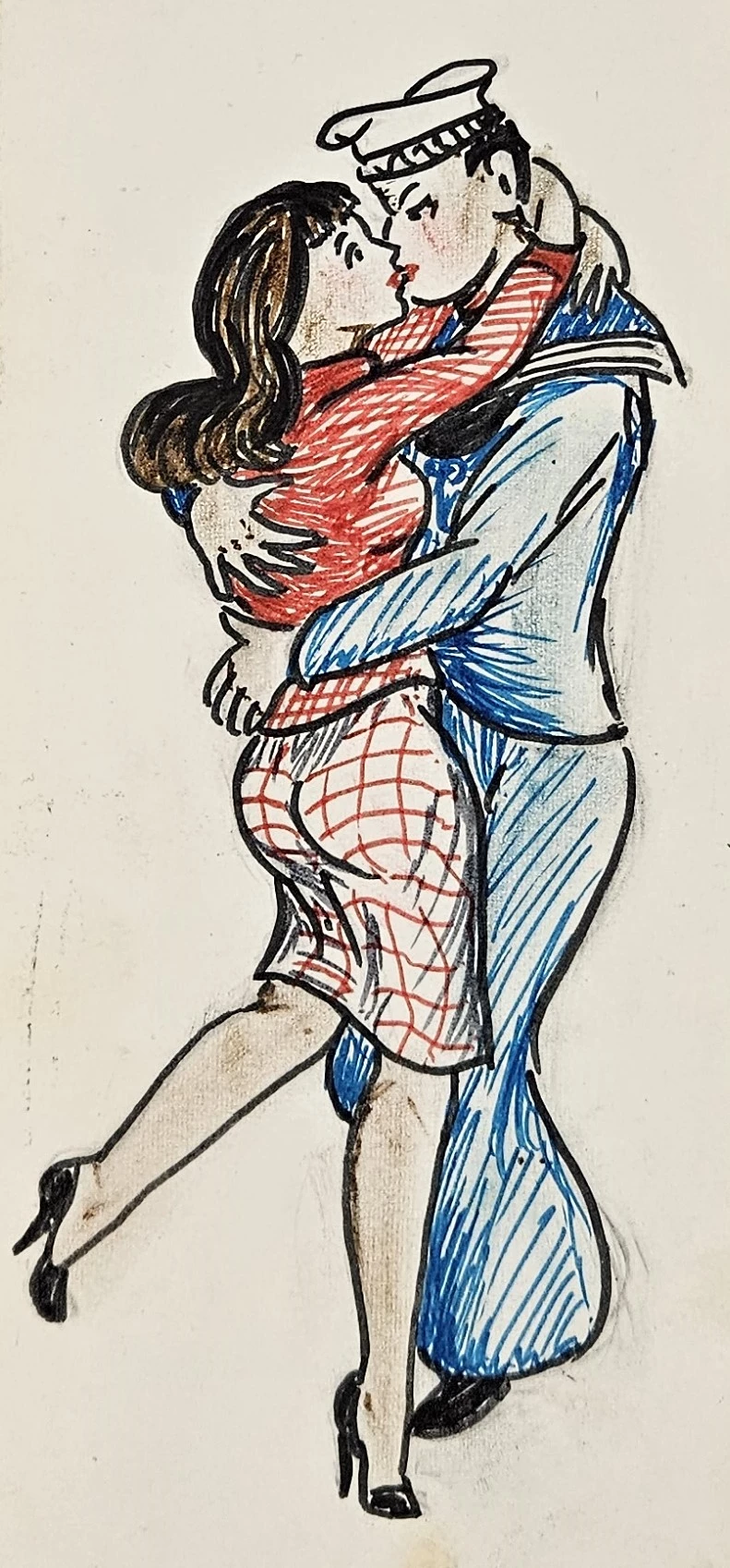

The designs in the collection also tell us about the trends of the day, and while some of these are intensely problematic and need to be addressed sensitively, we can also see how Jessie moved away from the more stereotypical representation of women as sex objects to create a more realistic depiction of women. This was unusual at the time, but then Jessie herself was also unusual – and blazed a trail for female tattoo artists working today.