Starting work on our new Celtic Village

, 20 December 2013

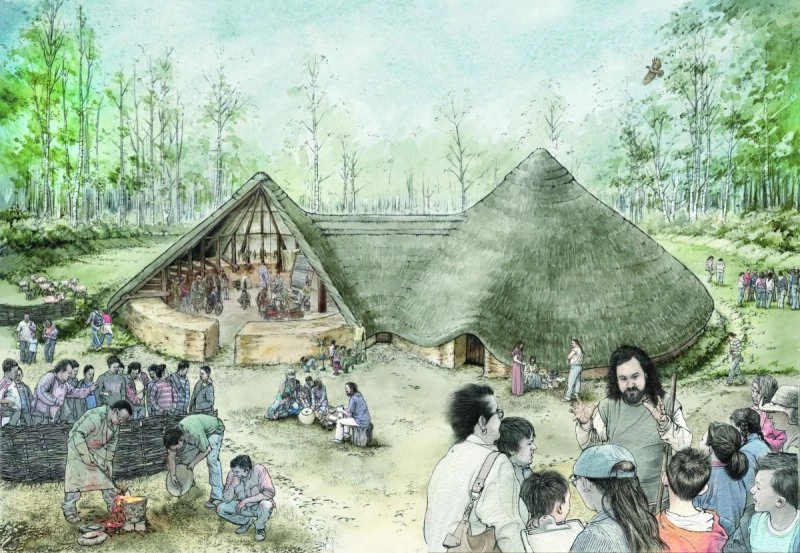

As many regular visitors to St Fagans will know, our much-loved Celtic Village was closed earlier in the year. Twenty years seems to be about the normal life-span for reconstructed Iron Age roundhouses – the timbers decay and they begin to get a bit wobbly after that. To replace it we're going to be building a new reconstruction based on a 2,000 year old Iron Age farmstead on Anglesey called Bryn Eryr, and just recently we reached a really exciting milestone along the way.

The Bryn Eryr roundhouses consisted of two buildings built side-by-side. Their walls were made of packed clay (probably mixed with grit and straw, like Wales's traditional clom-built houses) and the roofs were thatched. We've had a lot of discussions about what we should use to thatch them. Naturally the roofs of the original buildings haven't survived, but we do know that its Iron Age owners had access to spelt – an early form of wheat – because charred grains were found at the site. From there the argument goes, if they were harvesting spelt grains to make their bread they also had their hands-on a useful thatching material, spelt straw.

So, we thought, St Fagans is surrounded by farm land, we've got an excellent farming team, and lots of enthusiasm, why not try to grow a crop of spelt ourselves and see whether we can thatch our next Iron Age farmstead with it?

There are a lot of uncertainties involved in this, many things can go wrong between the idea and the harvesting but St Fagans is part of an EU collaboration which encourages just this kind of experimental research. So thanks to the OpenArch project, with its Culture programme funding, and a lot of advice from experts in the field (apologies for the pun), we've decided to give it a go.

A few months ago we ploughed 3.4 hectares (8.4 acres) just outside the main museum site. This looks like an enormous area when you're stood beside it, but we're told this is what we need in order to produce enough straw to thatch two large roundhouses.

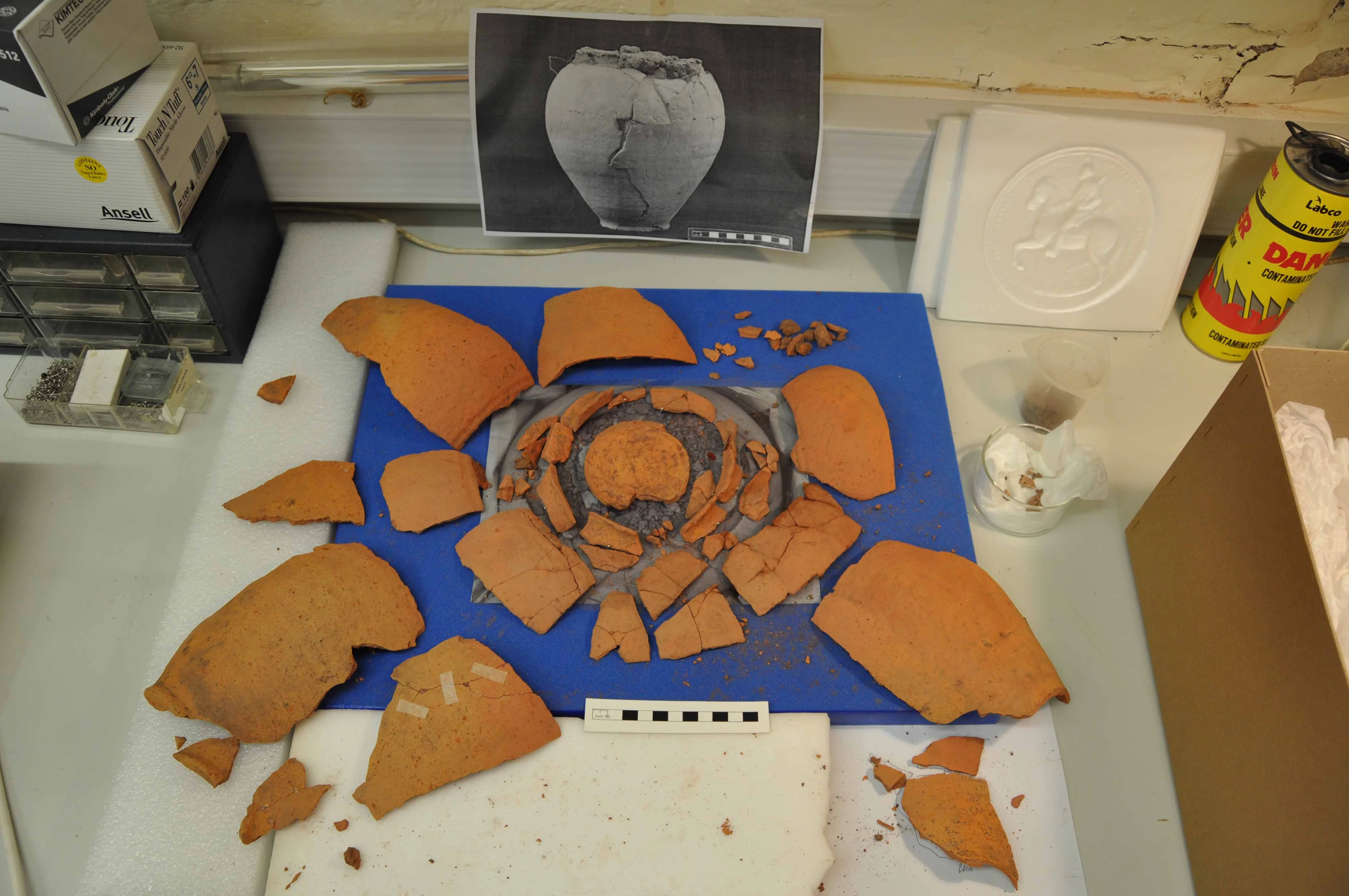

With the ploughing done, our Learning Team organised an opportunity for school groups to come out and see what we were up to. This was followed by the museum's archaeologists bringing together a team of volunteers who walked the area in search of any artefacts that may have been turned up by the plough. The finds from this have yet to be analysed but already we can see that the area had been visited by prehistoric hunter-gatherers, a 13th-century traveller who lost some loose change, and many other more recent people.

And then it rained, and rained and rained. Our spelt seed arrived and was placed in a barn, and still it rained. I was beginning to get very worried. It's all very well having a plan to grow a crop of Iron Age wheat, but that's not going to happen if the seed stays in sacks. Then a few weeks the weather cleared up, the ground dried sufficiently and we finally got a chance to plant.

Then we waited… Would anything happen? Had we left it too late? Would frosts / rain / snow put a stop to our plans? Happily not! Last week we found the first seeds had germinated. I’m going out to the field again today to check on its progress. Will the shoots be showing? Have we got the spacing of the seed right? Will the rabbits leave it alone? Will it grow tall? I feel like an expectant father all over again.