Fore-edge Paintings in the Library

, 12 April 2019

Many of the books in the Library collections at the National Museum Wales have attractive decorative techniques applied to the covers or text blocks. Decoration on text blocks, the combined pages of the book inside the covers, is particularly lovely because it tends to be hidden when they are on the shelves.

The most popular examples of decorating text blocks include marbling and gilding. But one of the most interesting techniques is the one known as disappearing fore-edge painting, which was often hidden underneath the other types of decoration.

Fore-edge painting was a technique that reached the height of its popularity from the mid-17th century onwards. It was usually applied to the longest section of the text block, the one opposite the spine, the fore-edge.

Two books in our special collections feature examples of mid-19th century disappearing fore-edge paintings. They are the two volumes of the second edition of the Memoirs of Lord Bolingbroke by George Wingrove Cooke, and were published in 1836.

When the book is closed you cannot see the image, only the gilt edges of the text block, but when the leaves are fanned, the hidden picture is revealed.

To achieve this effect, the artist would need to fan the pages, and then secure them in a vice, this means they are applying the paint not to the edge of the page, but to just shy of the edge. Once completed, it is released from the vice and the gilding would be applied to the edges.

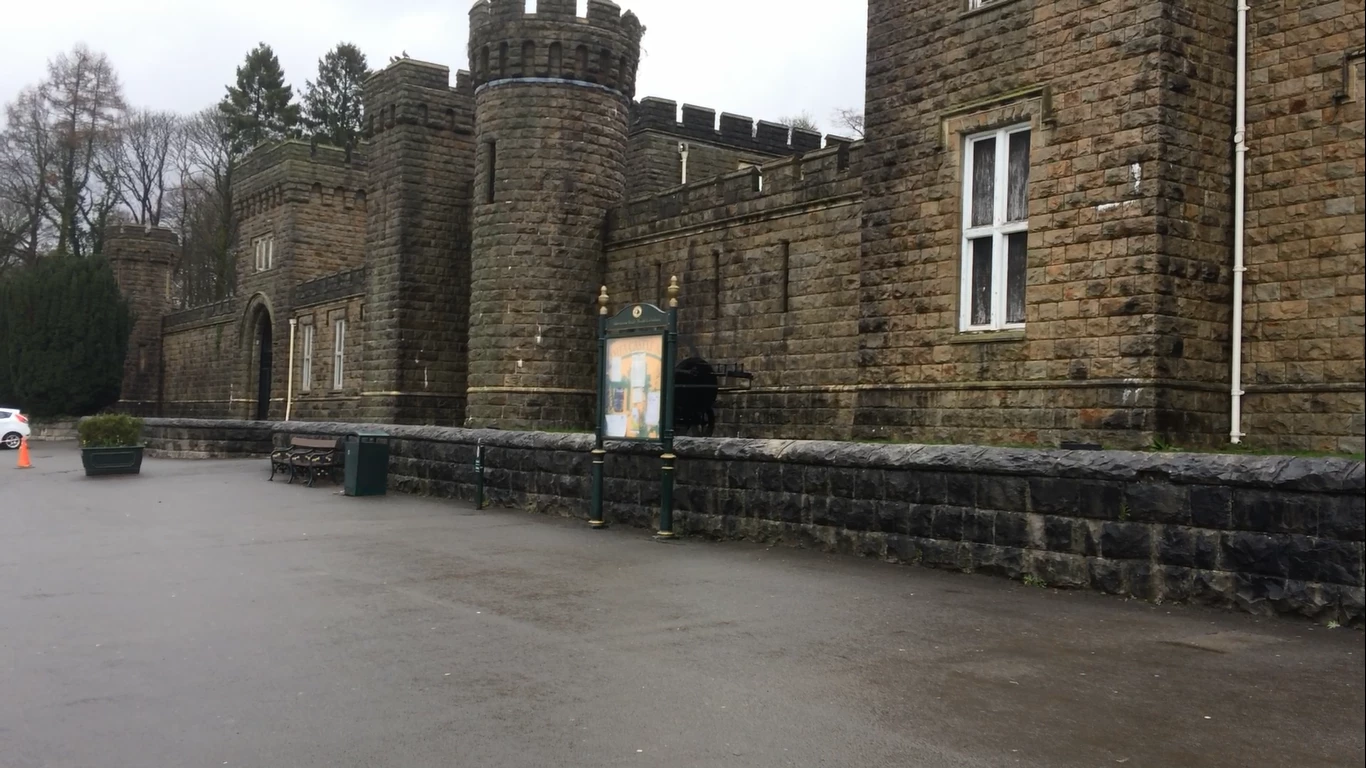

Landscape scenes were the most popular for this technique, and the ones on our books show Conway Castle and Caernarfon Castle.

Very often the motivation for a fore-edge painting was a demonstration of artistic skill, so it didn’t always follow that the images were related to the text contained within the book. These two volumes of Memoirs, do not have an obvious connection to the scenes painted. Lord Bolingbroke (Henry St John, 1st Viscount Bolingbroke 1678–1751) was an English politician during the reign of Queen Anne, and later George I, and is probably best known as a supporter of the Jacobite rebellion of 1715, but he does not appear to have any direct association with either Conwy or Caernarfon.

The volumes were acquired for the Library in 2008 from a rare book dealer, but we don’t know enough about their history to be able to tell when the fore-edge paintings were added. The first volume contains an inscription that states that the book was a gift to a T. M. Townley from his friend Samuel Thomas Abbot on his leaving Eton in 1843. Unfortunately we don’t know anything about either the recipient or the sender, so we can’t tell if one of them was ultimately responsible for painting the books.