A History of The Museums Branding

, 29 September 2023

If you can believe it, we keep a copy of every museum publication we produce. Yes, every flyer and brochure and after a while it starts to pile up! While in the process of ordering and categorising this mountain of coffee table litter and ephemera into a cohesive collection, it’s been fascinating to see the way that Amgueddfa Cymru’s branding has changed and evolved over the years. The logos and designs tell us not just about how the museum represents itself but also they tell us something about the time they were written in. So, let’s take a look at the museums branding and design over the decades.

In a museum brochure from 1968, the simplicity of the design is striking with its bold text and the solid red graphic of columns and pediment, which is the globally used symbol for museums (but more on that later). Yet for a modern eye it still looks old fashioned; there are no photos or even a colour gradient and it is printed onto plain white paper. The inside contains only small black text of museum department events, in a list, with little formatting. for example:

Zoology: In the Gallery near the Restaurant: Demonstration of Taxidermy of birds and mammals. 10am -12 noon

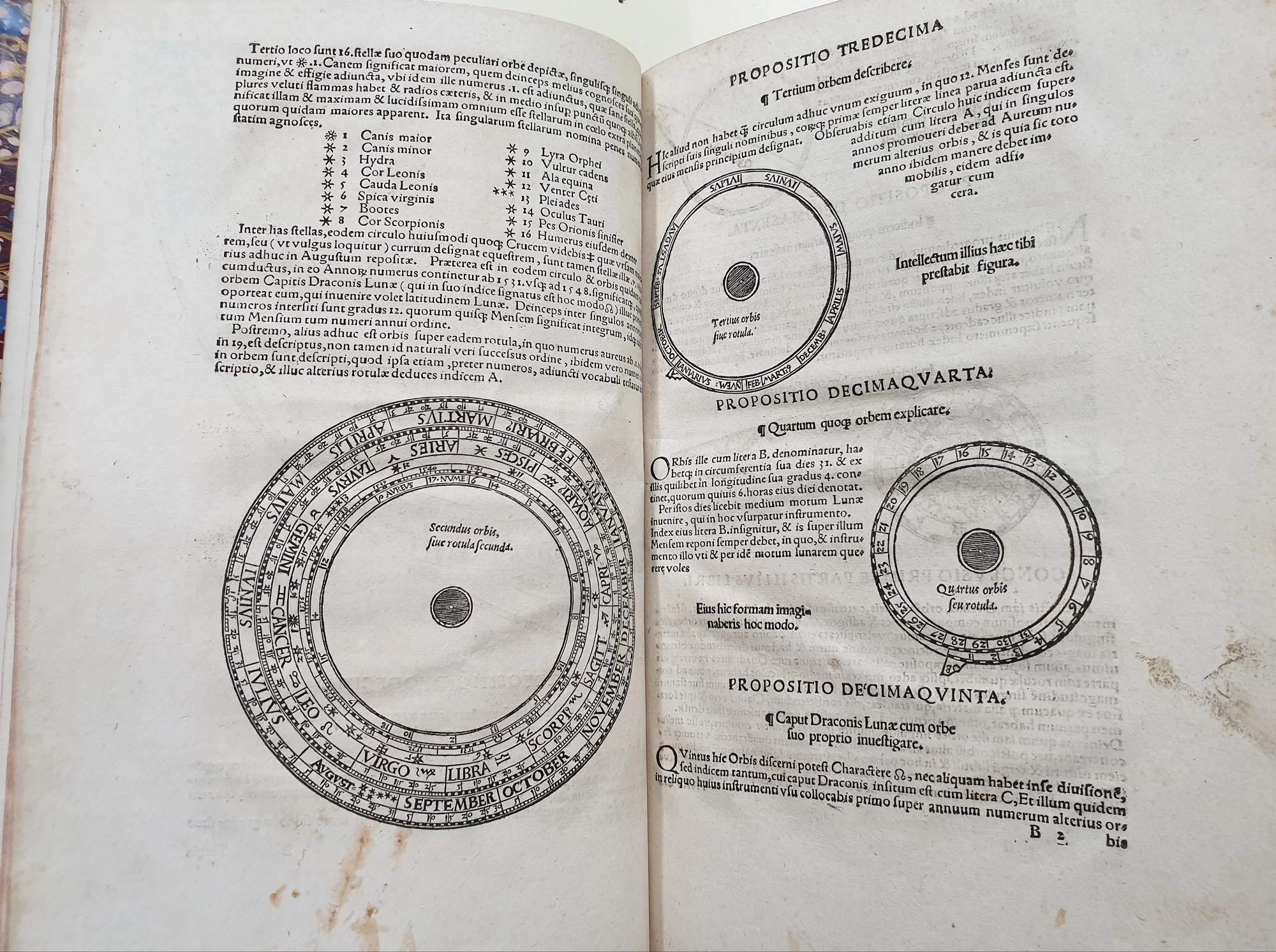

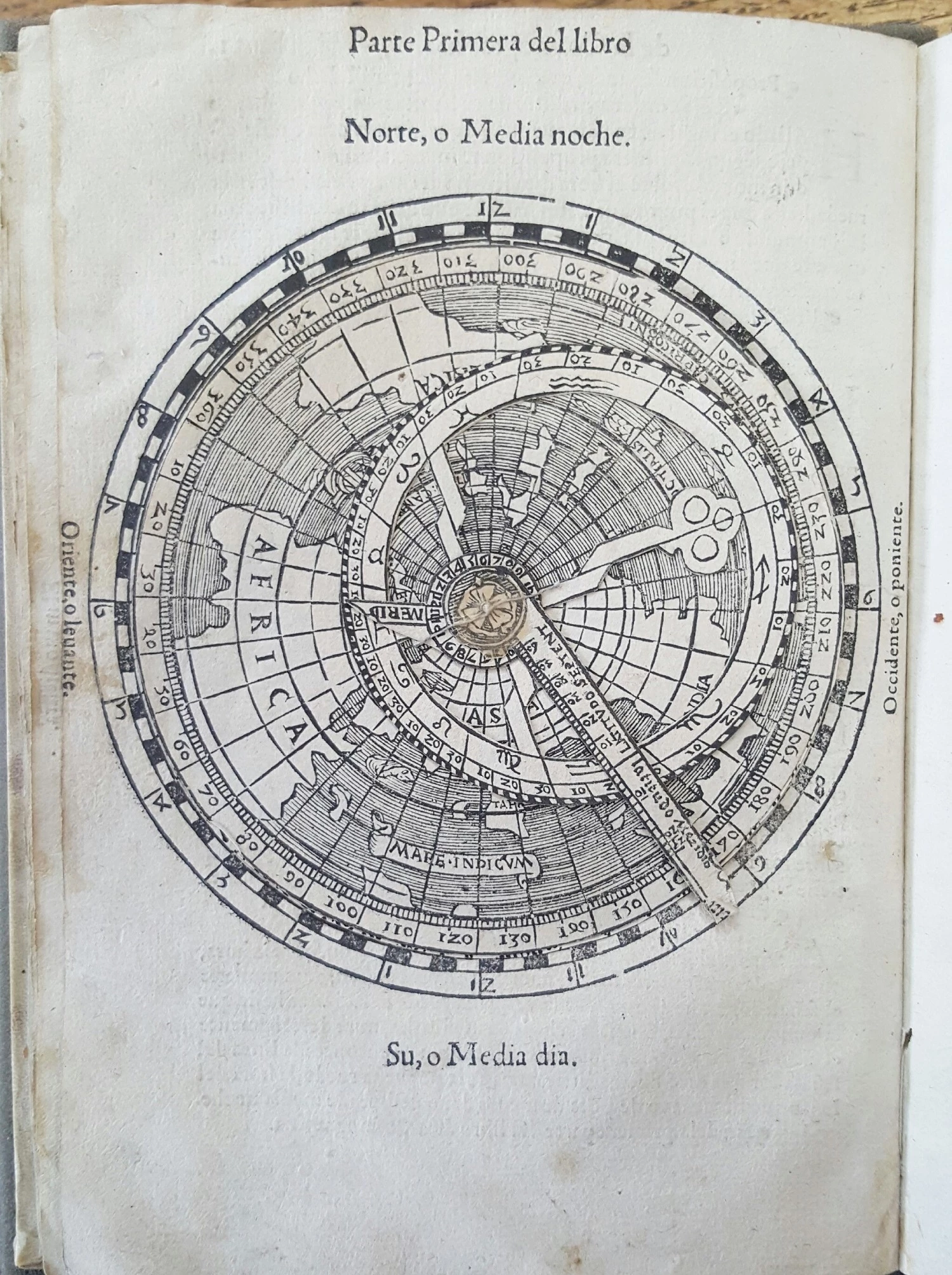

In 1969 we get a new look for monthly Programmes. This style sticks for the next decade. A bright solid colour fills the background, and the words “Amgueddfa Genedlaethol Cymru National Museum of Wales” are in a large clear bold text. The front of each issue has a large single black and white image that takes up the centre of the cover. This is however the only image the programmes contain, but maybe as a result the images picked usually look dramatic and intriguing. There is something reminiscent of album cover art about them. In the December 1969 issue the cover features a picture of a lunar landing module and the moon from space. Inside are details of a 3-day exhibition where the museum had genuine moon rock on display.

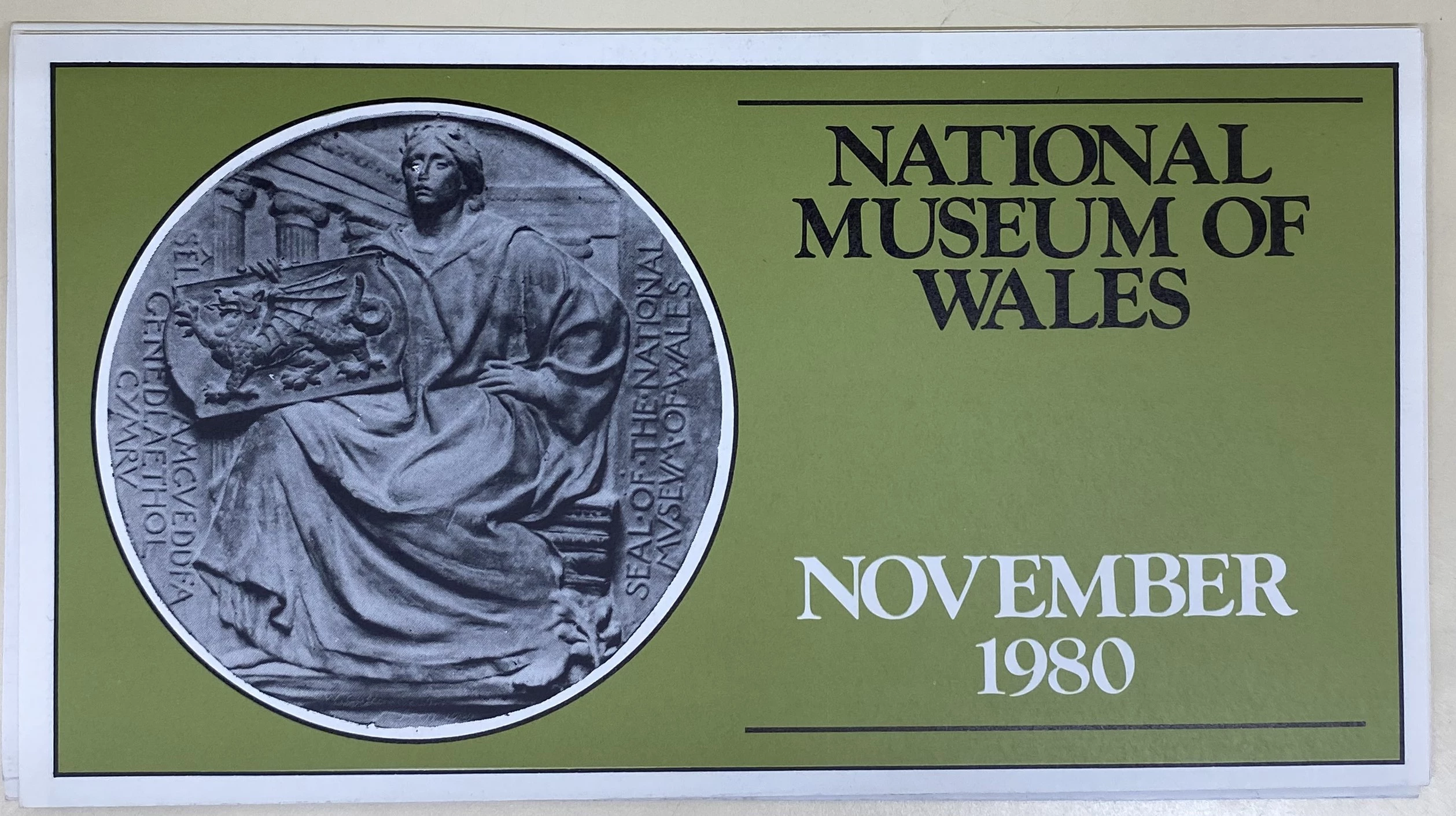

In the 1980’s we get a new look again, which we can see in the museum’s monthly programmes. But if it wasn’t for the date, you might assume it to be older than it is. The writing is in a traditional serif font and each issue has the same image a marble fresco of a woman holding a picture of the Welsh dragon with Ionic columns in the background. It is the Seal of the National Museum of Wales. It is an architectural feature of the Cardiff site that you can see today above the entrance of gallery 1.

It is an image that is meant to invoke a certain ideal of “The Museum” that it is grand, historic, noble, and “cultured”. The monthly programmes certainly work hard to solidify this visual brand, having the large logo/seal prominent on every issue that leans into the imagery we already associate with museums. As with the earlier 1968 programme both are invoking the image of the Museum as a grand marble Greco-Romanesque styled structure. This seal is then used in slightly different forms on all publications for the next decade and a half.

The icon for museums as a row of pillars with a triangle pediment on top is widely used. It is the image you will see on brown road signs or tourist maps to mark the location of a museum and certainly the National Museum Cardiff and the Roman Legion Museum do have that classic museum look complete with towering columns. It is an image that may well reflect what museums used to be like, opulent buildings that looked at foreign artefacts like Greek statues. But it is an image that now many museums are working hard to move away from. Ultimately as an icon it doesn’t really capture or express the totality of what Amgueddfa Cymru is all about, a diverse and varied family of museums that celebrate Welsh life.

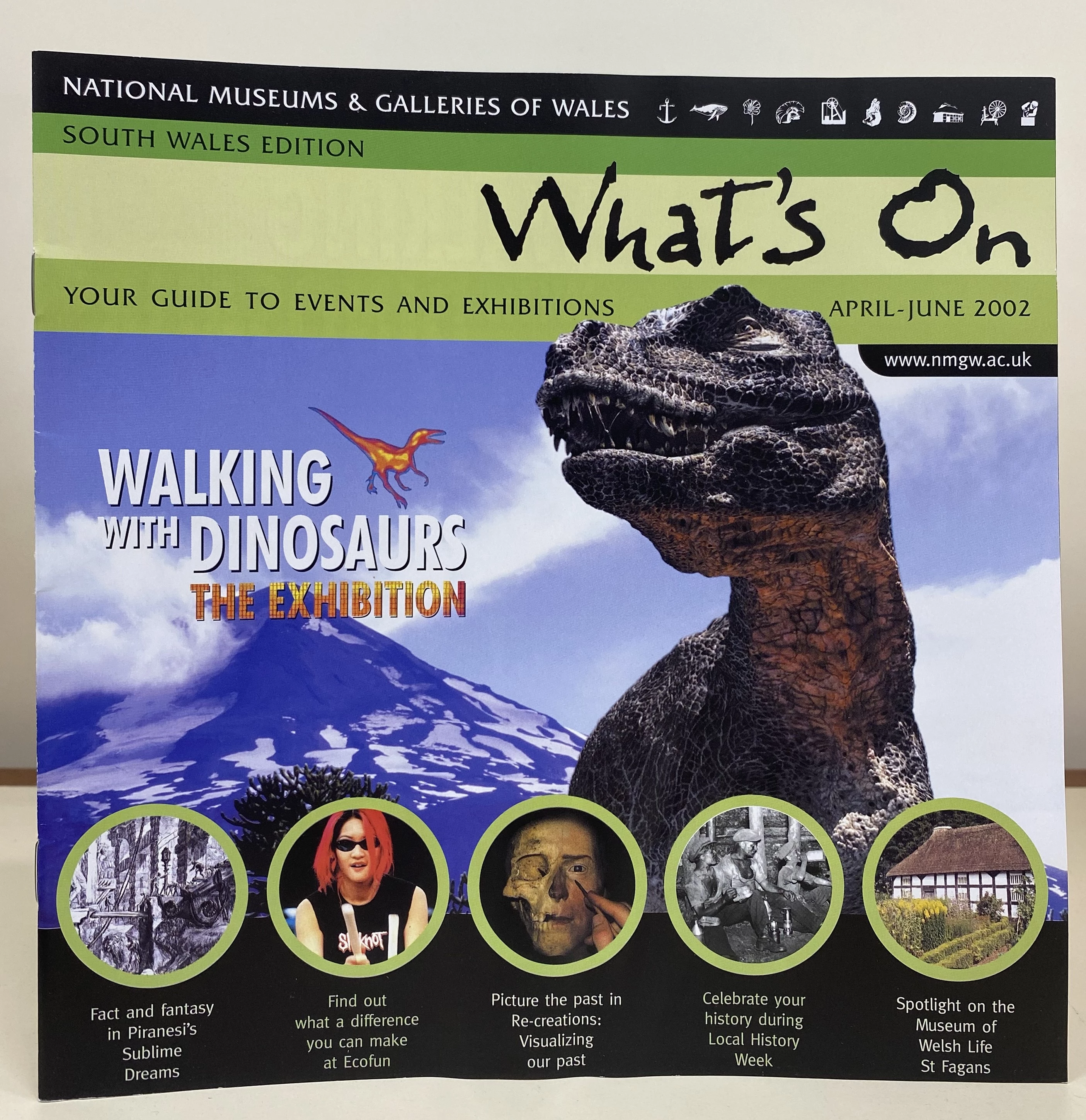

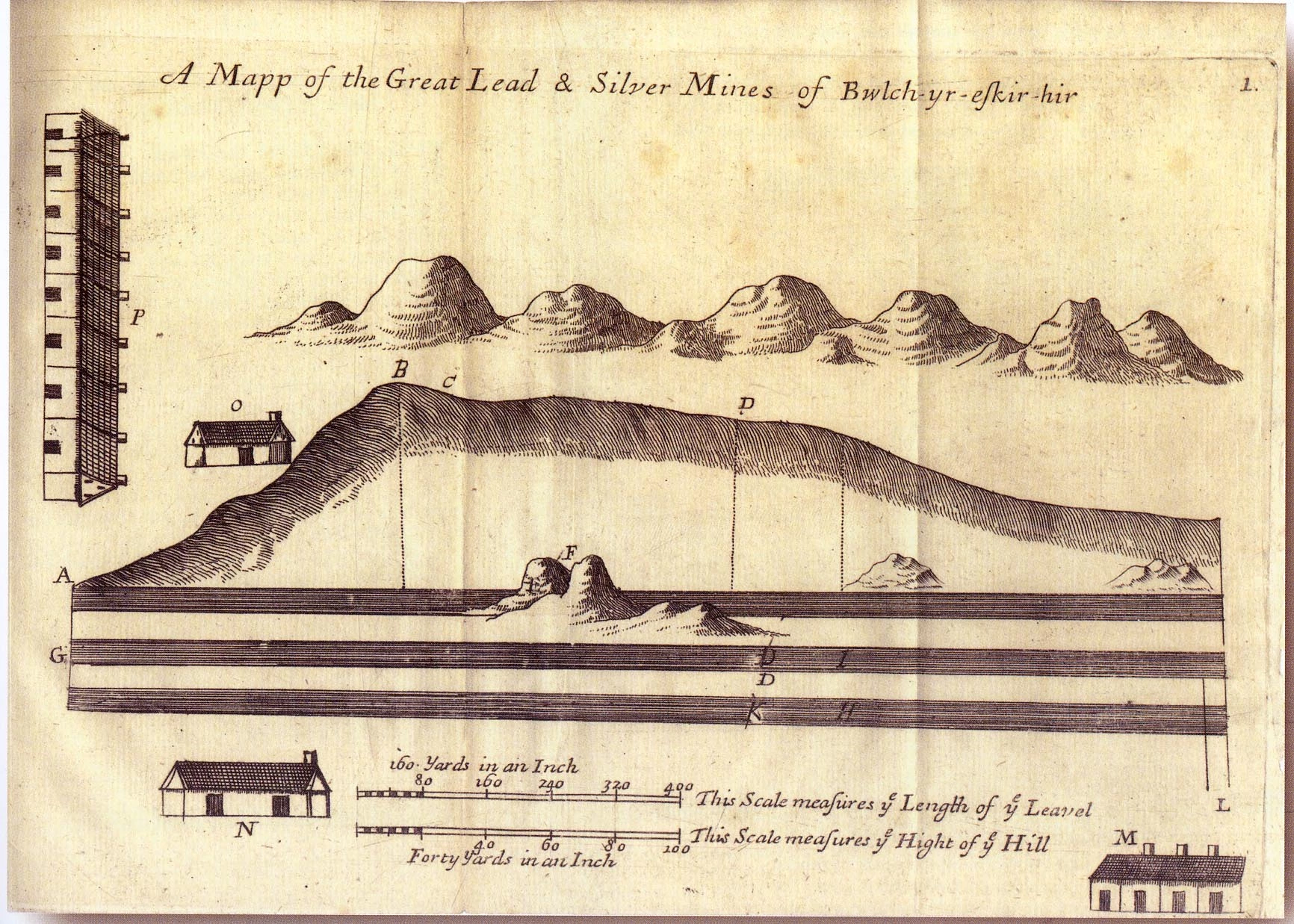

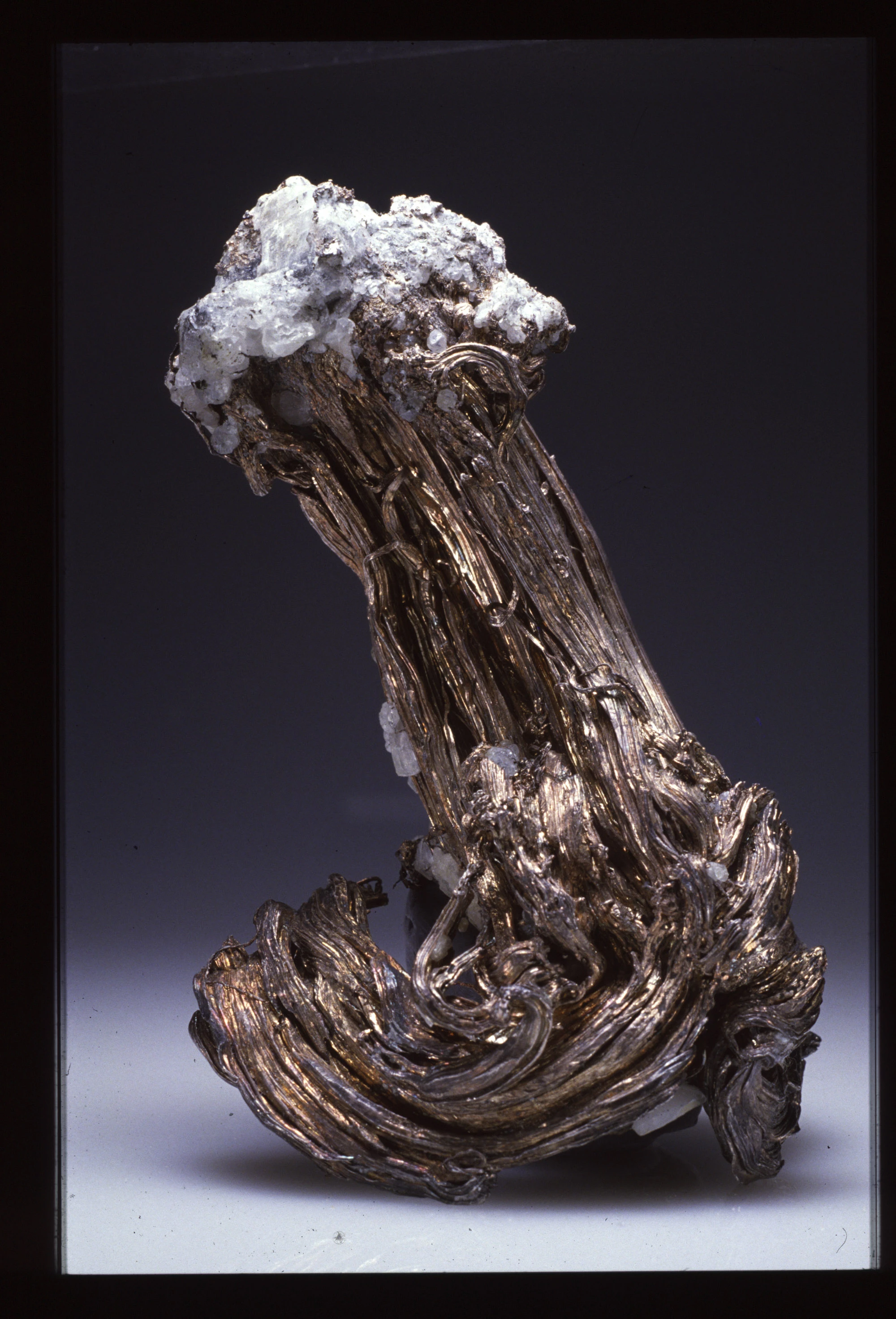

Then in 1995 there is a major rebrand. We have moved away from the traditional imagery of museums and galleries and instead have a range of icons that highlight the different parts of the museum’s collections including a spinning wheel, anchor, and steam powered machinery to name a few. It excellently highlights the diversity of what we have to offer. The graphics almost look like a website banner with clickable icons displaying the range of choices. The publications go through various changes over the following years with a greater focus on full colour photos, and a variety of graphics and fonts. The publications are exciting and colourful, but is there a downside? Some might see this iteration of publications as overly crowded and busy. Furthermore, there is no signal unifying image for Amgueddfa Cymru as an integrated organisation.

Then in the 2000’s a new rebrand ditched the icons and opted for words. The words “National Museum Wales” and “Amugueddfa Cymu” were placed at an angle to each other in a modern sans serif font for all publications. This echoes the priorities and vision of the museum in this era. Balancing the English and Welsh language at angles so that neither takes priority over the other. It is effective straightforward and unambiguous. However the thirty three characters at 45 degree angles do not work well on a small scale and can become cluttered and difficult to read. As more and more we switched to phones as our primary reading devices there was a greater need to have a clean simple design.

Since last year we have had a brand-new redesign. The Amgueddfa Cymru logo is written in a bold capitalized font, created for the Museum it emulates the look of an industrial brand like that which you would find on metal or bricks to show the maker; it reflects the industrial past of some of our national museums. For social media, where space is limited, we have a simple “AC” icon on a red background. Clean and simple bold texts work well for online platforms and this process of simplifying graphics has happened across many brands over the past decade as reading from phone screens has become the norm. Amgueddfa Cymru’s new design uses only the Welsh language title, further simplifying the design and highlighting the museum’s commitment to telling the story of Wales, from its earliest times, through its industrial transformation to the modern day. The font highlights the special characters that don’t exist in English, such as the “DD” which is has been linked together in “Amgueddfa” further showing our pride in the Welsh language.

Ultimately there will be pros and cons to any logo or icon. Often it is about what is right for the time, and what is best for the medium the icons will be on. Do you have a favourite?