Stories in the Stones - a film project by Angela Roberts

, 21 June 2020

As work to dismantle the houses begun – marketing officer Julie Williams realised that a film was needed to document the process and which could later be shown to visitors of the museum to tell their history and reveal the stories in the stones.

The company that undertook the film project was Llun Y Felin, run by Angela and Dyfan Roberts who lived nearby in Llanrug. Together they created the loveliest film entitled Stories in the Stones – a film which - like the houses - has stood the test of time and is still shown daily at the museum – and now, for the first time, online!

Here Angela Roberts looks back at some of her memories of the process of putting the film together.

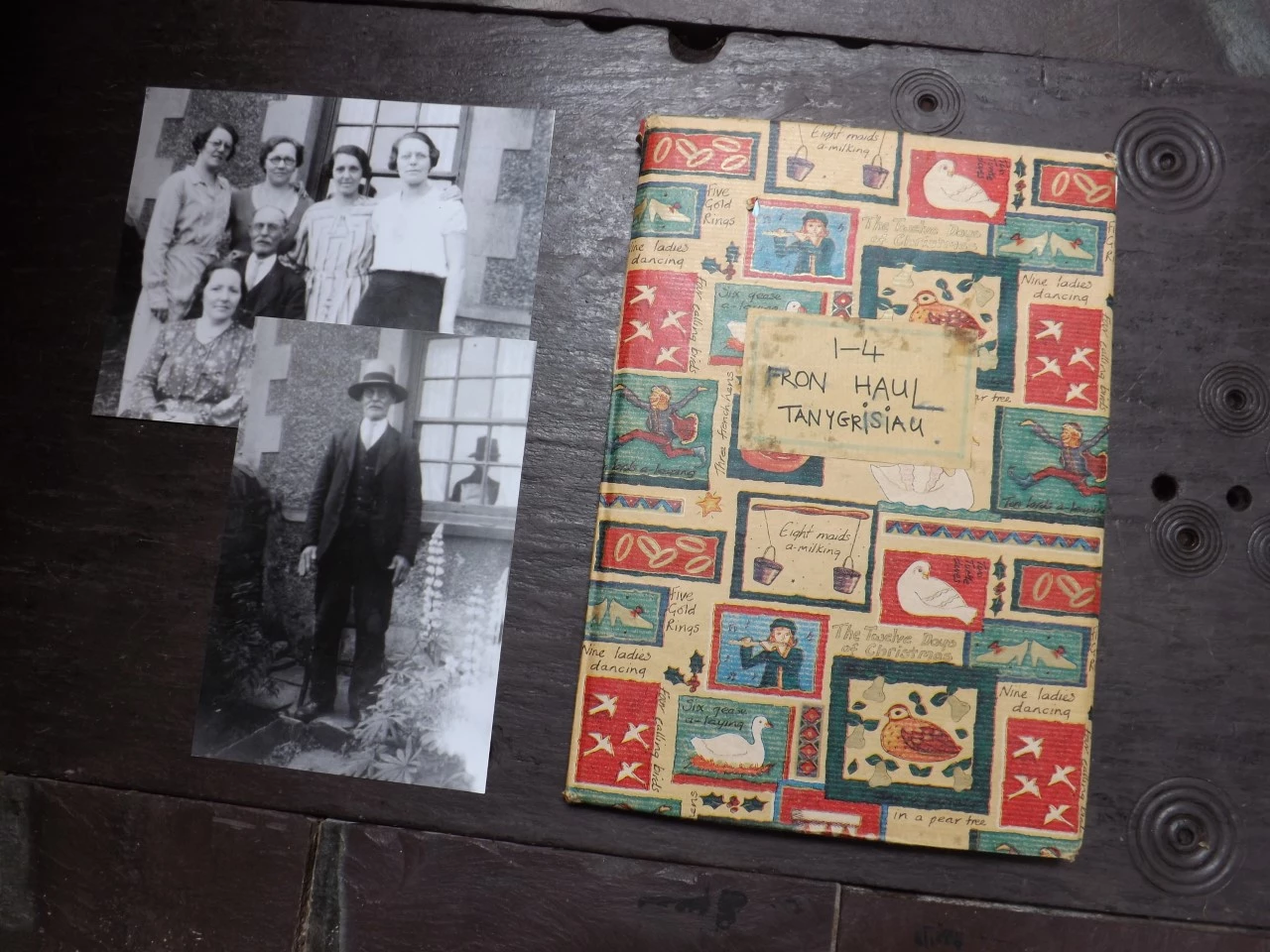

What makes a home? Is it bricks and mortar, or is it people? When the National Slate Museum chose our small ‘husband and wife’ television company to record the moving of four slate quarrymen’s houses from Tanygrisiau to the museum – it was the stories of those who had lived in them that I was particularly excited to unearth from the rubble.

Unusually, the names and occupations of all families and lodgers had been carefully documented – going right the way back to the houses’ very first residents 150 years prior. Slate, of course, was their raison d’être. ‘The Slate Quarries of North Wales’, published in 1873, describes Blaenau and district as a ‘City of Slates’ with parapets, kerb stones, chimneys and roofs hewn out of slate, and larders, kitchen tables and mantlepieces fashioned out of slate. Letters by an unknown author of that time read:

I had gone to the Welsh Slate Company’s quarry and, in returning by the rubble heaps, I came across a smart looking boy pulling out slabs from amongst the waste. I entered into conversation with him.

“For what purpose are you gathering stones?”

“To make slates, sir.”

“Are they not too small to make slates?”

“Not to make small slates, sir!”

The boy knew what he was talking about. All slate was useful. Hadn’t he been working in the slate quarries since the age of six?! The writer continues:

“I reached the quarry at noon, and was allowed the privilege of steaming my clothes before the peat-fire in the weigh-taker’s hut. The men soon came filing in, each man taking a can from the fireplace. I entered a conversation and soon found that in politics they were eminently radical, in sympathies generally warm-hearted, and as impulsive as Celts in general.”

A little condescending? Perhaps. But radical, warm-hearted and impulsive – of course they were! And I was soon to find out that nothing much in that respect had changed down all those long years.

Trips with Julie and Dyfan to meet former residents of 1-4 Fron Haul and their relations were an out and out joy. And it was such a privilege to sit and listen to their stories over biscuits and home-made cake and endless cups of tea.

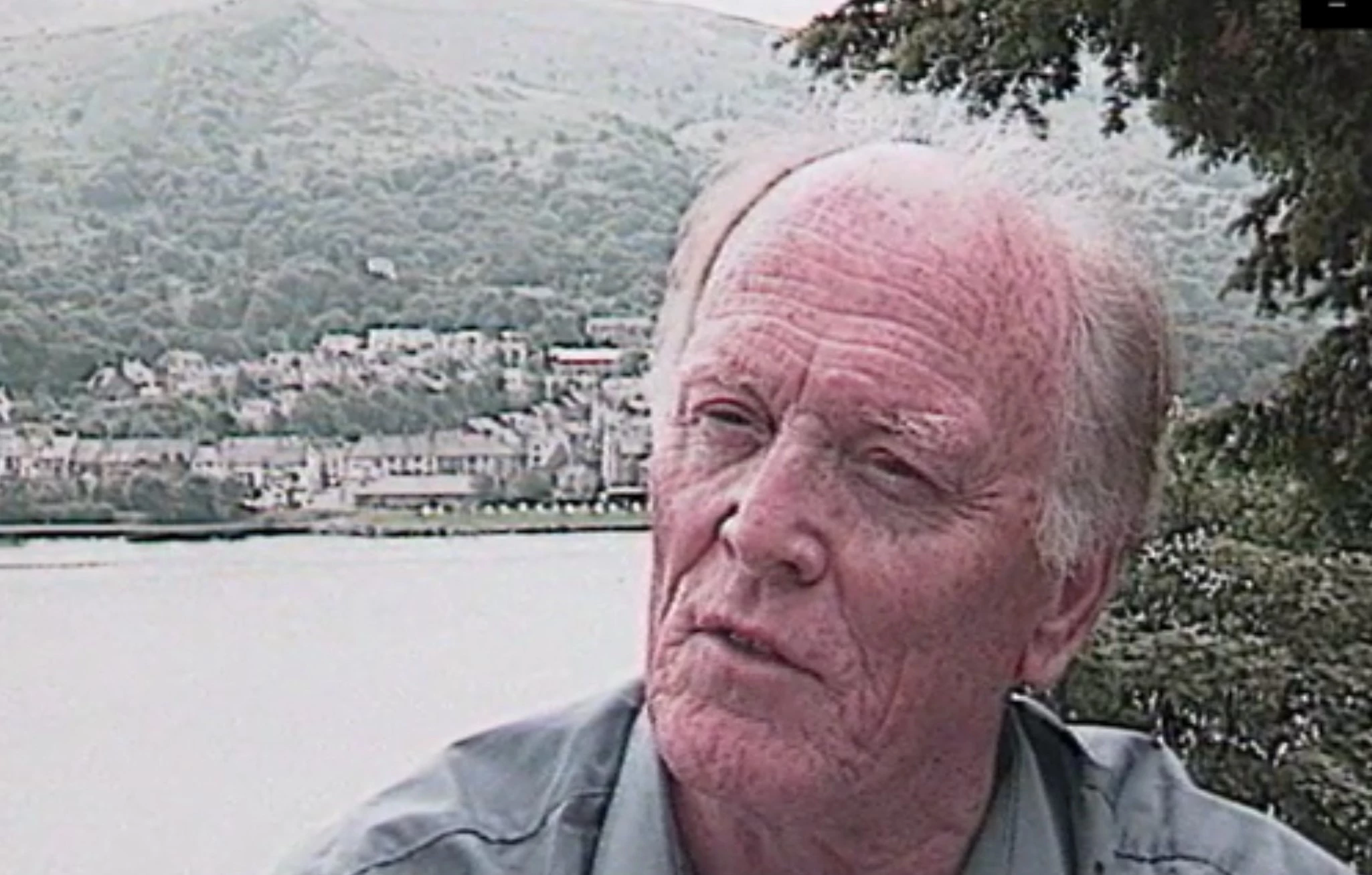

Aneurin Davies was in his nineties at the time, still running his own farm and still as mischievous as he must have been as a child. He couldn’t help chuckling telling us about the tricks he and his friends used to get up to – placing a halfpenny on the train track for a passing train to squash it to the size of a penny, and then straight off to the shop to try and exchange it for sweets (unsuccessfully as it turned out)!

Marian Jones was another who spoke lovingly of a special childhood - with memories of bikes, hulahoops and hay fields, of collecting tadpoles and binging on sweet stolen sugar peas.

Robin Lloyd Jones recalled visiting his grandfather in number 3 - the portrait of Italian revolutionary Garibaldi at the top of the stairs, the Bible and pipe on the table, the taking turns to bathe in front of the fire in an old tin bath.

While Doreen Davies thought back with a smile to her mam cooking up feasts in the cast iron range. “How on earth she did it, but we always had plenty to eat… oh, she was especially good at making apple tart and cacan gri – you know, Welsh cake.”

Abel Lloyd had lived in Fron Haul the longest - for over 76 years, indeed, since his birth. He remembered sheets being pinned to the ceilings to make the home warmer and talked of collecting water from the downpipe and the well to make tea – as the water from the tap had a really bad taste. But, rather than the hard times, most of all he remembered the good times and the joy of living in a close community.

Like Marian and Aneurin and Robin and Doreen, he talked of carnivals and get-togethers and kindnesses and a village of Aunty this and Uncle that – even if neighbours weren’t actually related by blood at all. Like the others, he had a lifetime of stories to tell us about 1-4 Fron Haul.

And, as Robin himself so eloquently answered me,

“What makes a home? Not, in the end, the cushions, the wallpaper, the colour of the paint – but the stories of the people who lived there, the stories in the stones.