Swansea has a whole host of treasures just lying within its midst, from the Red Lady of Paviland to the 4200 year old flint dagger that formed the basis for Saving Treasures; Telling Stories first Community Archaeology project, ‘The Lost Treasures of Swansea Bay’. With the rip roaring tides, miles of beaches and hidden caves waiting to be discovered, you’d expect the sea (for which the city is named) to occasionally stir up something significant; but what about an unassuming Welsh livestock farm? Doesn’t sound like the setting for a major archaeological discovery, does it? Suprisingly, that’s exactly where local man, Geoff Archer, picked up one half of a Middle Bronze Age copper-alloy palstave axe mould dating somewhere between 1400-1200 BC.

It was over two decades ago when Geoff first picked up a metal detector, having first taken it up as a hobby after he got married. But it wasn’t until he retired last year that he was able to really get out into the field, and armed with a pair of wellies and a brand spanking new detector, he decided to venture to one of his old jaunts – a farm not far from his home.

“Over the last few nights I’d been thinking about going to the farm and something was telling me to go to the right hand side of it, just to walk the fields,” he explains, “so that’s what I did.” After traipsing around in the mud for a few hours, Geoff stumbled upon a patch of uneven terrace he couldn’t help but investigate.

Unearthing History

“I got to the lumpy, bumpy parts, had a couple of signals – nothing much.” But then Geoff had another signal, “a cracking signal” and realised it was time to dig around in the dirt to find out what it was. Figuring it would just be another case of random odds and sods, or a coke bottle lid (they find an abundance of litter!) he was surprised to hear a clunk.

“I hit this bloomin’ great big stone, so I dug around it, lifted up a clod of earth” and underneath yet another stone he noticed something interesting inside the muddy cave, something not made of rock. “What the heck’s that?” he thought, picking up the oddity with care.

“I pulled it out and on the back end of the mould there’s, like, ribs.” This prompted Geoff to recall a discovery he made about 15 years ago, when he wasn’t so rehearsed in Bronze Age metalwork.

“Going back, must be about 15 years ago, I found an item - I didn’t know what it was. I wasn’t experienced enough then. So this item, I took it home and I put it in the garage, as most detectorists do!” He had a feeling it was important but wasn’t sure why.

After a few years of picking the item up off his work bench and trying to decipher its meaning, Geoff decided to take it up to the kitchen and do some research. “So I started buying books to research Roman, believe it or not, alright? So, I bought this book and I was looking through it. I got to the part for the Stone Age, read that. Then I got to the Bronze Age, and I turned a couple of pages and there was the item I’d found! Bronze Age Axe Head. My jaw just dropped, right? And the Bronze Age Axe Head had ribs on the outside.”

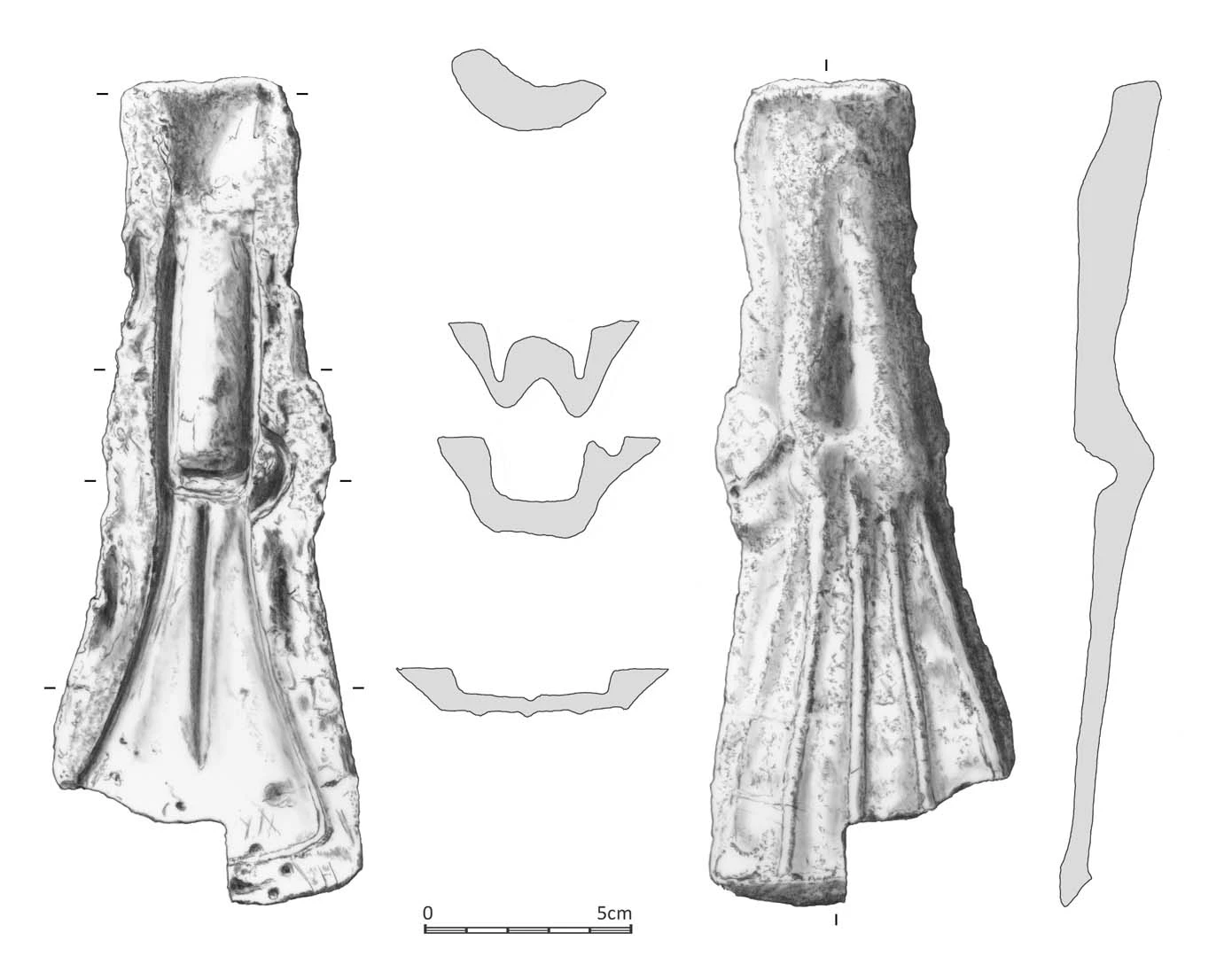

Devastatingly, Geoff has misplaced the axe head, which he is now, more than ever, desperate to locate – and even more upsetting still, it’s the same type of axe as the mould he discovered 15 years later would have been built to make. “It’s what they call a loop, I think it’s got two loops on this one, each side, where they used to put, if you can imagine, the Bronze Age axe head. It’s flat, but this part at the back, its round and they put it over the wood and then they loop it, they tie it onto the wood to secure it.”

Monumental findings

When Geoff uncovered the mould, he immediately realised its importance thanks to his previous finding – but he still wasn’t entirely certain of what it was he’d discovered. “On the inside of the mould, there’s like a round piece, like in the middle part. I honestly thought at that time that it was a bit off a tractor, because it was so… the engineering of it, the precision engineering of it! But in the back of my mind I was thinking it can’t be off a tractor because it’s got these ribs at the back from this Bronze Age axe that I found.”

After digging out some modelling clay and experimenting, he came to the realisation that what he’d found was an axe head mould. Geoff phoned up one of his buddies at Swansea Metal Detectorist Club for a second opinion and after a positive diagnosis by them both, he took it along to a club meeting.

“As it so happened, it was our ‘Find of the Month’ meeting!” Geoff explains. “So I won find of the month for the artefact and Steve, our Finds Liaison Officer, said ‘you’d better show this to someone in Cardiff because they are going to be interested.’ So, photographs were sent to Cardiff [National Museum of Wales] and they wanted to see it. I went with Steve to Cardiff and the mould’s been there ever since!”

Mark Lodwick, the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) Cymru Co-Ordinator at The National Museum of Wales in Cardiff confirmed Geoff’s identification and has recorded the item so it can be used in further research and study.

Under the Treasure Act, the mould isn’t classed as ‘treasure’, so why is it so special? “It’s the only one that’s been found in South West Wales,” Geoff enthuses, “and it’s the second one that’s been found in Wales. The other one was found in a hoard of axes in Bangor in the 1950’s, so this is the first one that’s been found since then!”

Preserving the past

Geoff is in utter disbelief that he was the one to stumble across the important artefact, which has been conserved at the National Museum of Wales, Cardiff, but, eventually he’d like it to end up back home at Swansea Museum.

Having reported the axe mould to the museum, Geoff sees this as an important part of his role as a treasure hunter. Letting other people view the item, he says, “gives other people a chance to understand about their locality, of what’s been going on.”

“I think it opens up a new chapter in [Swansea’s history]. There’s a bit of history regarding the Bronze Age but to find something like an axe making product in Swansea, which has never been found before - it opens up a new chapter of where these people were living and how far were they living on the fields of that farm,” explains Geoff. “That’s my quest now I suppose, is to try and find out – keep walking the fields and I might find the other half, I don’t know.”

With hopes of the axe mould ending up in Swansea Museum, Geoff is keen that people will be interested in viewing his remarkable find. “The more publicity it gets the better!” he says. “The more people who know about this the better as far as I am concerned, because it’s the first one to be found in South West Wales and the second one to ever be found in Wales – so don’t tell me that’s not important.”

To discover more about Swansea’s Bronze Age history and see some fascinating Neolithic archaeological artefacts visit Swansea Museum, entry is free!

Words: Alice Pattillo