Fossils are cool, and everybody knows it. Dinosaurs, ammonites, trilobites – all extinct but living on in our imagination, in films and books and documentaries and children’s stories. We watch ‘JurassicPark’ and ‘Ice Age’ on TV, collect fossil bones and shells on the beach, and amuse the kids with a remote-controlled plastic dino until the batteries run out.

But what about all those fossils that no film director wants to know about? 99% of all organisms that ever lived on Earth are extinct. Only a fraction of these were dinosaurs, so what about the rest? Billions of species have evolved and disappeared, and most have only ever been heard of by small groups of scientists who devote their lives to charting the history of evolution. Here’s a little test: do you know Lepidodendron, Meganeura, Rhynia, Bothryolepis, Calycocoelia or Lambelasma? Two of them are plants, one is a dragonfly, one fish, one sponge and a coral - ten points if you can put them in the correct groups.

Sometimes those bizarre fossils that only geeky scientists are interested in develop an unexpected life of their own. I am interested in corals – but not those colourful ones that make up the Great Barrier Reef, this beautiful living structure that can be seen from space. No, I picked an obscure group of corals that has been extinct for 250 million years. These corals are called rugose corals, and they look a bit like ice cream cones. They lived in the sea of course, little tentacles sticking out of a hard skeleton, some in shallow water, others quite deep. Most were only little, a few centimeters in size, although there are some that grew to half a meter in length. One of these has just reached a certain level of fame, and this is its story.

The mystery fossil

Two years ago two colleagues of mine were looking for brachiopods and trilobites in a remote corner of northeastern Iran. It was hot and dry, and where we in Britain have road signs warning of mud and flooding, in Iran they have signs warning of blown sand and collisions with wild camels. Doing geology is great in these areas, because you do not get any pesky vegetation growing in the way of beautiful rocks.

My colleagues, Leonid Popov (Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales), and Mansoureh Ghobadi Pour (Golestan University, Iran), did find plenty of fossils that day in the desert, but one rock contained something unusual. It was mostly buried inside the rock but the little bit that was sticking out looked a bit like a rugose coral. Leonid and Mansoureh knew exactly how old these rocks were. What they did not realise at the time, when they brought the fossil back to Cardiff for me to check out, was that they were too old for rugose corals.

Old corals

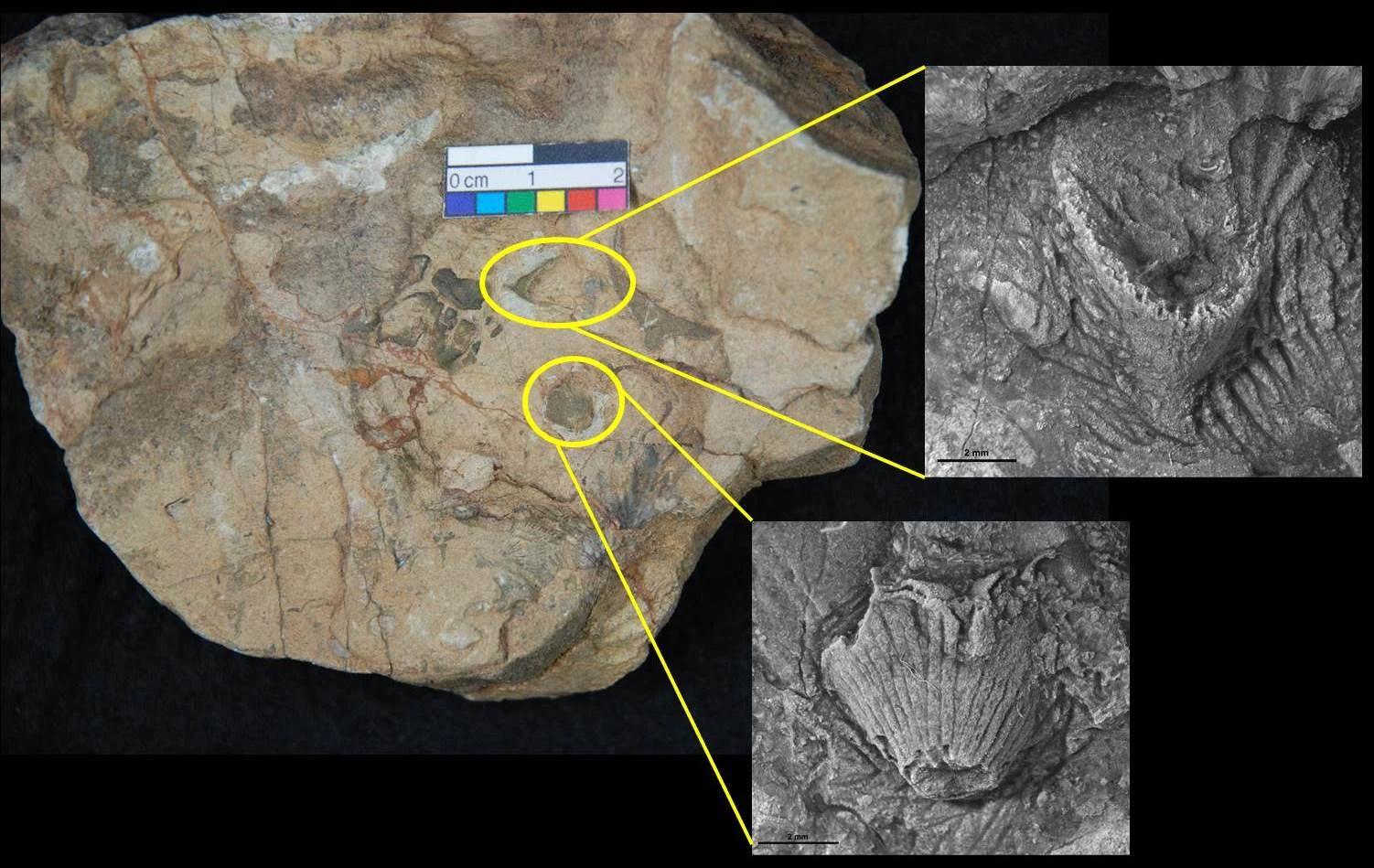

Corals are an ancient type of organism. Several different kinds have existed, most groups of corals are now extinct. The rugosans are not the oldest, but they are pretty old. Early rugose corals have been found in Northern Europe, North America and Australia, in rocks of Upper Ordovician age (about 450 million years old). The rocks in Iran which Leonid and Mansoureh were walking on are Middle Ordovician (462 million years). Therefore, if this new little fossil from Iran really was a rugose coral, it was going to be the earliest known one. Excitement all around, because everyone wants to find a first, but you have to do this sort of thing carefully, because you do not want to claim a first, then be proved wrong and make a fool of yourself. Because there are some sponges at that time which also look like ice cream cones, so we needed to be sure before shouting it from the roof tops.

Identifying rugose corals is not easy. You need a geological lab to make at least a couple of thin sections of the fossil. These are slices of rock thinner than a human hair, so thin that you can shine light through them and look at the structures inside. At the National Museum, we have the lab and we make lots of thin sections. But this is a destructive technique – in the process of finding out what’s inside the rock you lose your fossil. What if you only have one or two fossils, and you don’t want to destroy it? I started looking around for what we call non-destructive analytical techniques, and after a couple of unsuccessful attempts ended up at the Diamond Light Source synchrotron in Oxfordshire.

Fossils and X-Rays

Synchrotron X-Ray Tomography works a bit like an X-Ray in hospital, when you have broken your arm. Only the X-Rays are much more powerful – they can penetrate rock. At the Diamond synchrotron, this had only been tried once before, and the fossil then was preserved very differently (as pyrite) compared to ‘my’ coral (calcite and silica in a carbonate rock). Leonid came to Diamond with me, and together with Robert Atwood from Diamond we worked around the clock for three days – in that time I only had four hours sleep and I was completely shattered at the end of it. But just doing the analysis was not the end. The data coming out of the synchrotron were only ‘raw’, and they needed to be rendered, cleaned, edited, loaded into a different programme – this is what Robert did, and only after all that we found out whether the technique actually worked.

Robert did some amazing magic with the data, and it turned out that the technique really had worked. We were looking at a 3D reconstruction of the beast inside the rock, without ever having touched the rock. The fossil was still intact, it was still partly buried, and we also had the information we needed to describe it. For a palaeontologist this is pretty amazing stuff.

Mystery solved

From the images and the 3D reconstruction it was immediately obvious that this fossil was not a sponge, but that it really was a rugose coral. This was the second sensation. Definitely a rugose coral, we are certain of the age of the rocks, and it predates the previously known oldest rugose coral by 5 million years – quite a margin, even in Palaeozoic palaeontology. We called it Lambelasma because it has some characteristics of that genus – even though in the future we will probably find that it is actually a new genus, but we need more fossils to be able to decide that. That is quite difficult to organise, due to the remoteness of the area where this one came from.

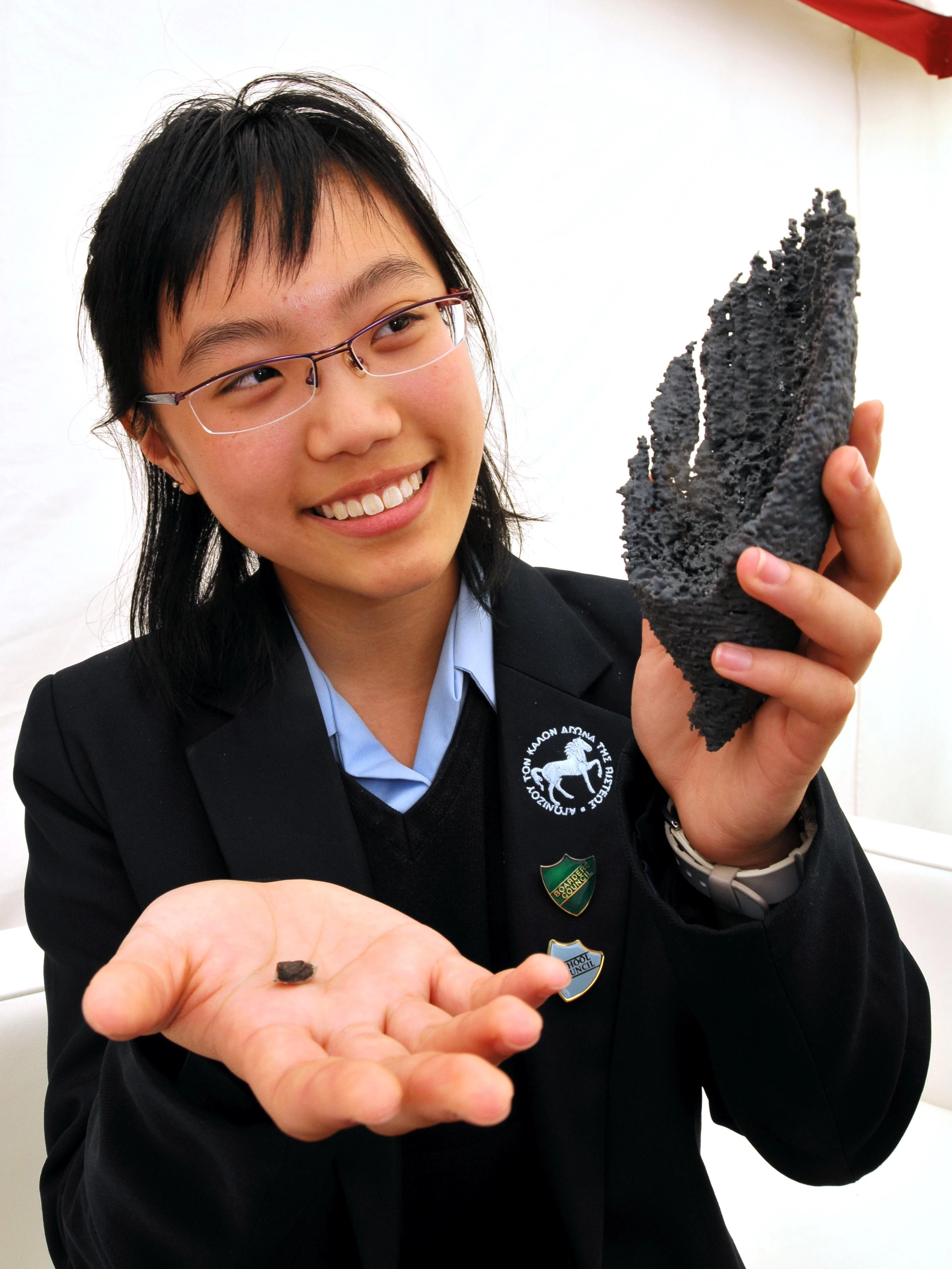

A conference in Oxfordshire and another one in Dublin, scientific publication, press release, and radio interview later, everything calms down. Until, six months later, an e-mail from the Diamond press office asks if I can come to the Cheltenham Science Festival in two weeks’ time. Apparently, 14 year old Christy Au from Headington School in Oxford picked our research as the subject to write about as part of Diamond’s ‘Light Reading’ competition; and won it! Her little story describes the feelings and experiences of the little fossil inside the rock, waiting to be discovered, and it is absolutely amazing.

Science and Art

This was all quite short notice, but a sudden burst of activity and a lot of help from many different people – most of all Sheng Yue from the University of Manchester – meant that Diamond was able to produce an upscaled 3D model of the coral. The model was nearly 20 cm long and much more presentable than the 1.8 cm long original fossil.

Christy came to Cheltenham thinking she was just part of a normal school trip to the Science Festival – but then, to her amazement, got ushered into the VIP area for a an award presentation. She met some of the team involved in the research, met the fossil and the 3D reconstruction, was photographed from all angles, and her story was read out by Professor Alice Roberts. Suddenly, Lambelasma had taken on a life of its own. This obscure little fossil, that, normally, would only get half a dozen geeks excited, was now on a public platform. Everyone was talking about it. It definitely had the X factor.

So what about Lambelasma now? It has all gone quiet again, and the fossil has gone back to the collections at the National Museum in Cardiff. Maybe you’ll come to visit the museum and happen to see it there. Look closely, because it really is only little. Hopefully you won’t think ‘Oh, it’s just an obscure little fossil, half-buried inside a small piece of rock’. Instead, think how much work it is to uncover the secrets of our Earth, and what wonderful stories are hidden inside each piece of rock.