Original Rock Stars

, 18 May 2016

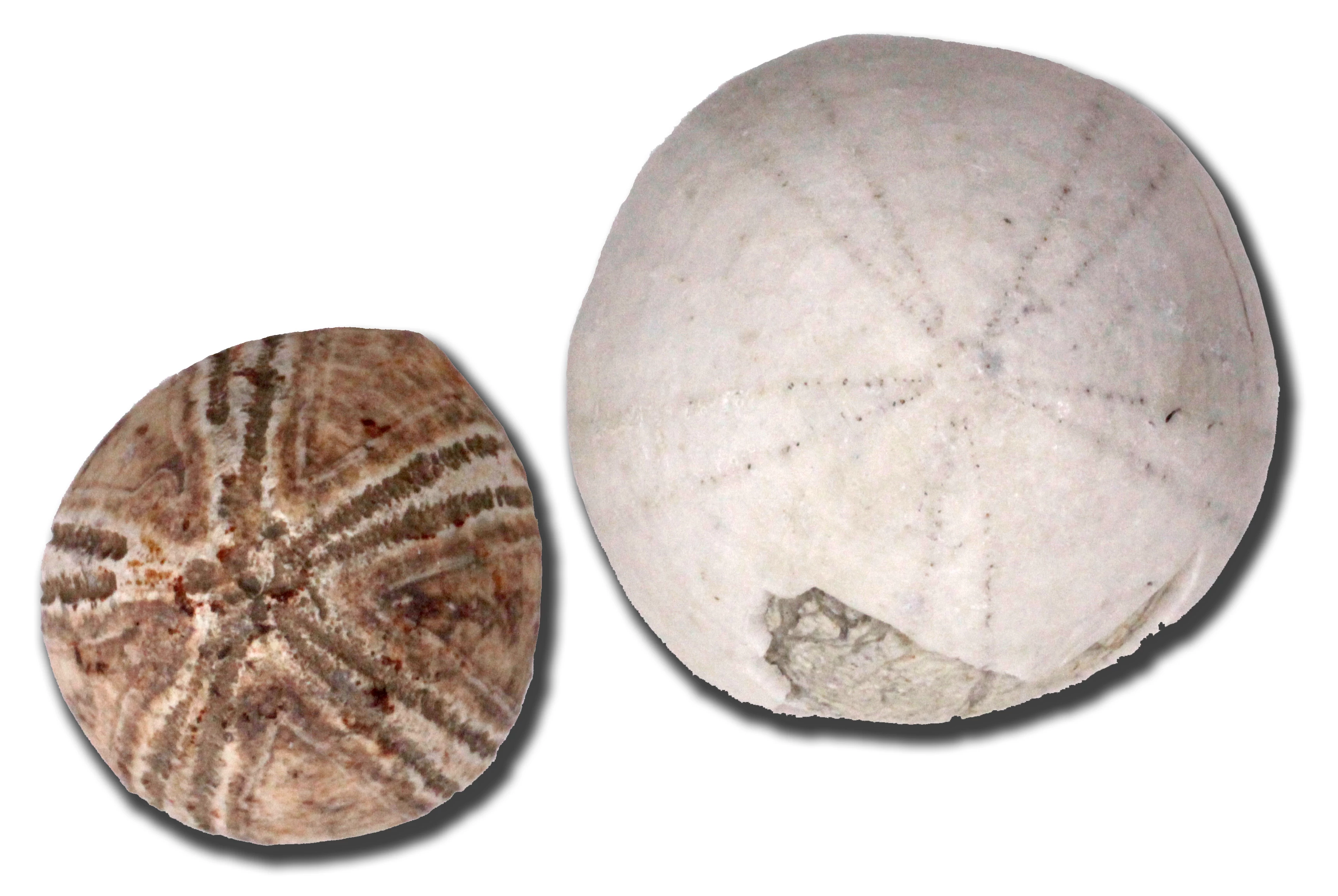

This blog is about fossils whose beautiful patterns have intrigued us for as long as we’ve been human. These animals survived the evolutionary power struggles of the past to leave their relatives in today’s oceans. They are the Sea Urchins, or to give them their scientific name, the Family Echinoidea - Echinoids to their friends.

A ‘Hedgehog’ by name, but not by nature

Their name comes from the Greek ‘Echinus’, meaning Hedgehog, because of their spines. People in the Middle Ages had the idea that each kind of land animal had a matching version living in the sea; sea-horses, sea-cows, and so on. So the spiky Echinoid was naturally called a Sea-Hedgehog. This might sound daft today, but we still call the Echinoids’ cousins “Starfish” though we know they’re nothing to do with fish at all !

Like little armoured aliens

The bodies of echinoids are really strange, almost like something from science-fiction. Being covered in massive spiny stilts you can walk on is weird enough, but inside their box of a shell they’re even more peculiar. They have a multi-purpose organ called the water vascular system. It’s a central bag of fluid connected to five lobes which lead to many tiny tubes coming out through pores in the shell. These are its tube-feet. It can move them around by changing the pressure inside the bag. They’re very handy for dragging itself along the sea floor, sensing the surroundings, and for getting food to its mouth. Some burrowing echinoids can even stick a tube foot up above the sand to get oxygen from the water.

Their basic body plan has proved to be very well adapted to a life of sea-bed scavenging. They move along like armoured tanks eating up whatever they can find; mostly algae, but their set of five toothed jaws can deal with a varied diet.

Cherished by the Ancients

The beautiful shells of echinoids have fascinated humans for a very long time indeed, maybe because they’re so different from other animals on the planet. Most animals have just one line of symmetry and an even number of limbs. But echinoids and their cousins the starfish can show star-like five-fold symmetry.

We know that this struck many people in the past. Ken McNamara gives the following two examples in his book “The star-crossed Stone” about the rich folklore of echinoids.

The oldest example of a collected and labelled fossil, is an echinoid with Egyptian hieroglyphics inscribed on it about 4000 years ago. It was found “in the south of the quarry of Sopdu, by the god’s father Tja-Nefer”. Sopdu was called the god of the morning star - he was a kind of border-guard god, and it’s been suggested that echinoids were important to the Egyptians in some way in their travels to the afterlife.

But human fascination with echinoids stretches back much, much further than that; long enough for the great ice sheets to have advanced and retreated across Britain four times since. About four hundred thousand years ago in what is now Kent, someone chose to make a tool from a flint containing a fossil echinoid. Most flint tools have two cutting edges, but this one may have been left unfinished on purpose. If the maker had chipped the flint to make the other edge, the fossil would have been destroyed. What is amazing is that this person was not a Homo sapiens like you or I, but either a Homo heidelbergensis or a very early Neanderthal (Homo neanderthalensis). Other humans were collecting fossils before members of our own species left Africa.

Trevor Bailey, Senior Curator – Palaeontology. This blog was adapted from a gallery tour I gave at the National Museum Cardiff.