More than meets the eye

, 7 April 2017

An insight into our display at the 2017 RHS Cardiff Flower Show

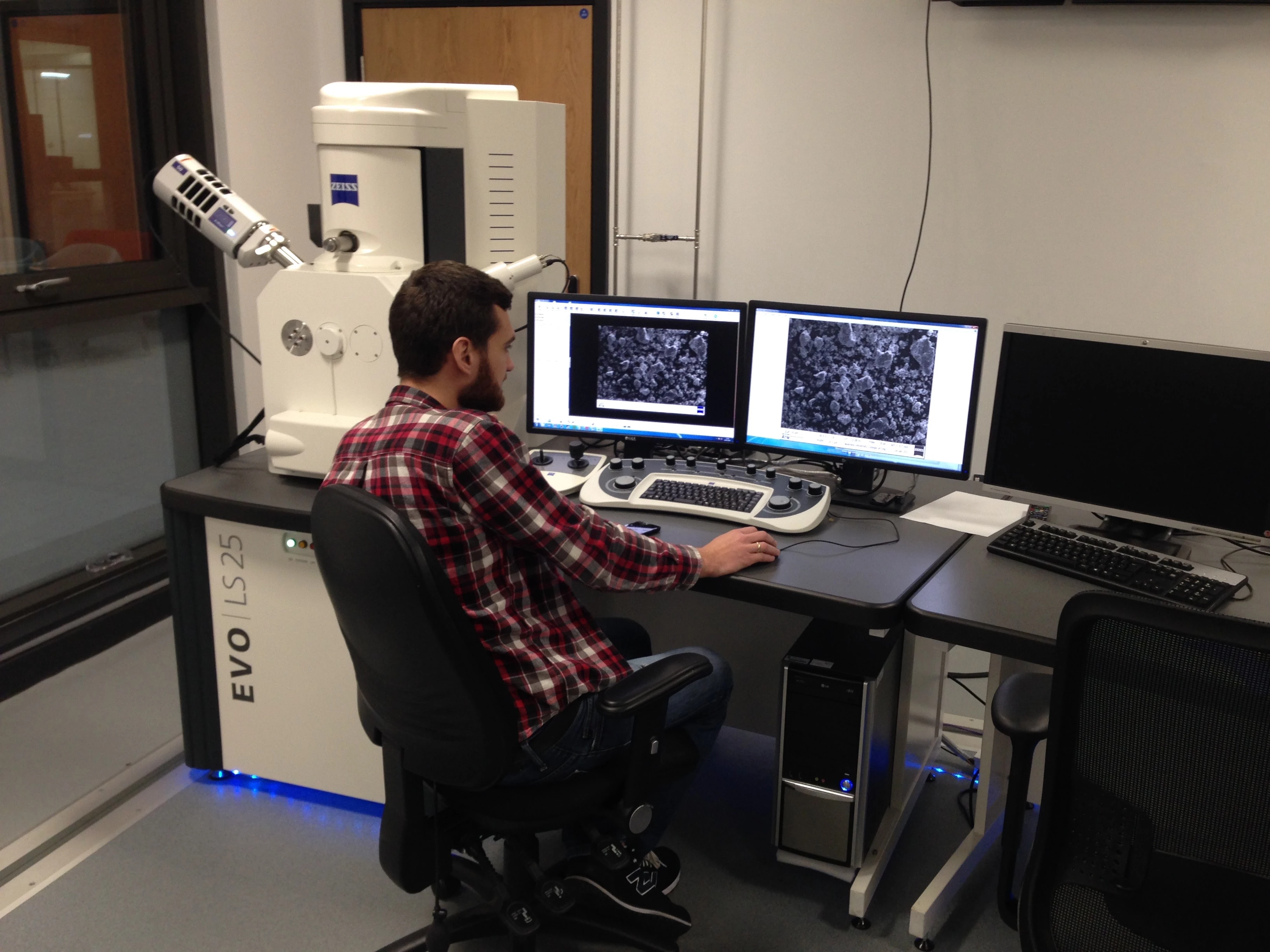

Visitors come into our marquee to see a display about wood & Welsh woodlands. There is an array of wood samples, wax models, taxidermy, insects, as well as live and pressed plants. Visitors know they are seeing a display by Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales, but do they realise that if they look a little deeper, in the same way that one of our scientists does down a microscope, it is showing them the daily work of the museum too?

The Flower Show to us is similar to one of our temporary exhibitions, but lasting three days instead of six to nine months, and we get ready for it in much the same way. Items for display are chosen and located, sometimes not a simple task when you look after 1 million or so botanical specimens. The correct sized cases need to be found to stop people from touching the historic specimens (which in the past may have been treated with chemicals to guard against pests). Delicate wax models, which have been made to show museum visitors plants all year round, need to be protected from the elements. Tiny preserved insects have to be extracted from the systematically ordered entomology collections, and remounted with miniscule pins in display drawers.

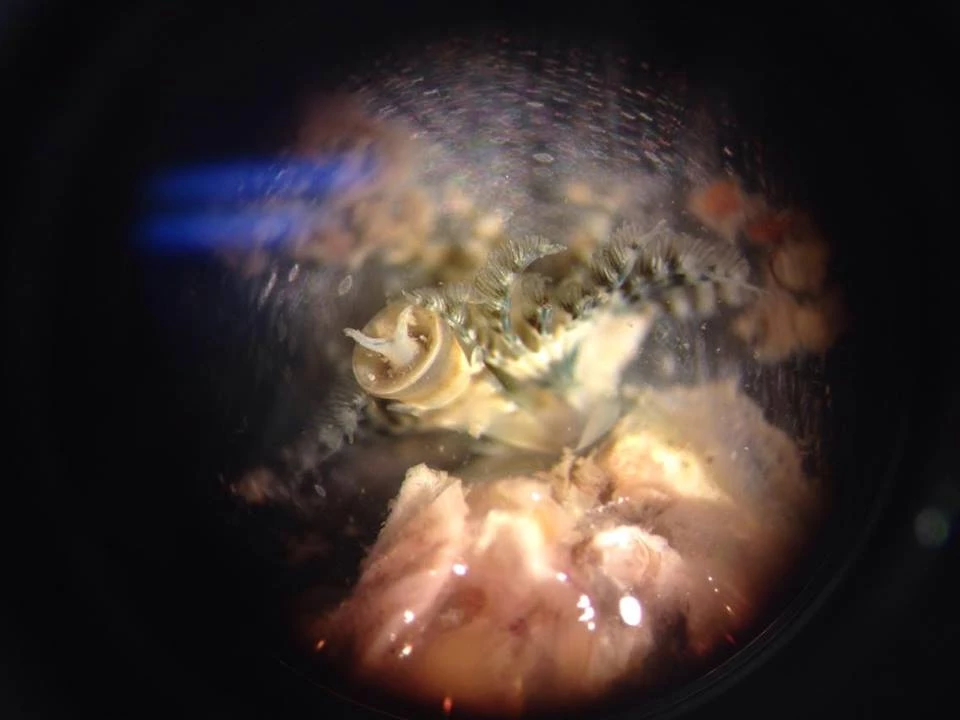

In the display, woodland mosses form an intricate garden. This gives us the opportunity to help visitors distinguish between different moss plants of the woodland floor. It also reflects how we carry out our scientific research, we do DNA/molecular work on dried plants from the herbarium, and conversely we sometimes need fresh material.

Acrylic panels hang at each end of the marquee, showing Welsh woodland tree silhouettes with their leaves, dried. These are not only artistic representations of the trees, they also show the technique we use for attaching delicate pressed plants onto card for storage in the herbarium. Thin strips of adhesive material are placed strategically along the plant to hold it safely on the card. This allows our botanists to easily remove the straps if they want to study the plant under a microscope, away from the card. The plants used in these panels have been collected specifically for the Show and have been pressed in the same way we would for long-term storage in the herbarium. They would also last for hundreds of years if kept out of the light.

Prints of a few of the hundreds of botanical illustrations in our collection adorn the marquee walls. These prints have been framed and mounted using standard museum techniques. They are not only intricate artworks, but are scientifically accurate representations of the plants they show.

Thank you for giving us the opportunity to show you our unique collection of specimens with a Welsh woodland theme. The RHS Cardiff Flower Show, with funding from the players of the People’s Postcode Lottery, has enabled the Natural Science Department to work with our colleagues from other departments. Our other museums have also helped us this year, bringing you clog-making, wood carving and garden conservators from St Fagans National Museum of History.

Why not keep up to date with what's happening in the Amgueddfa Cymru marquee over the weekend by following the @CardiffCurator Twittter account. Hope to see you there.