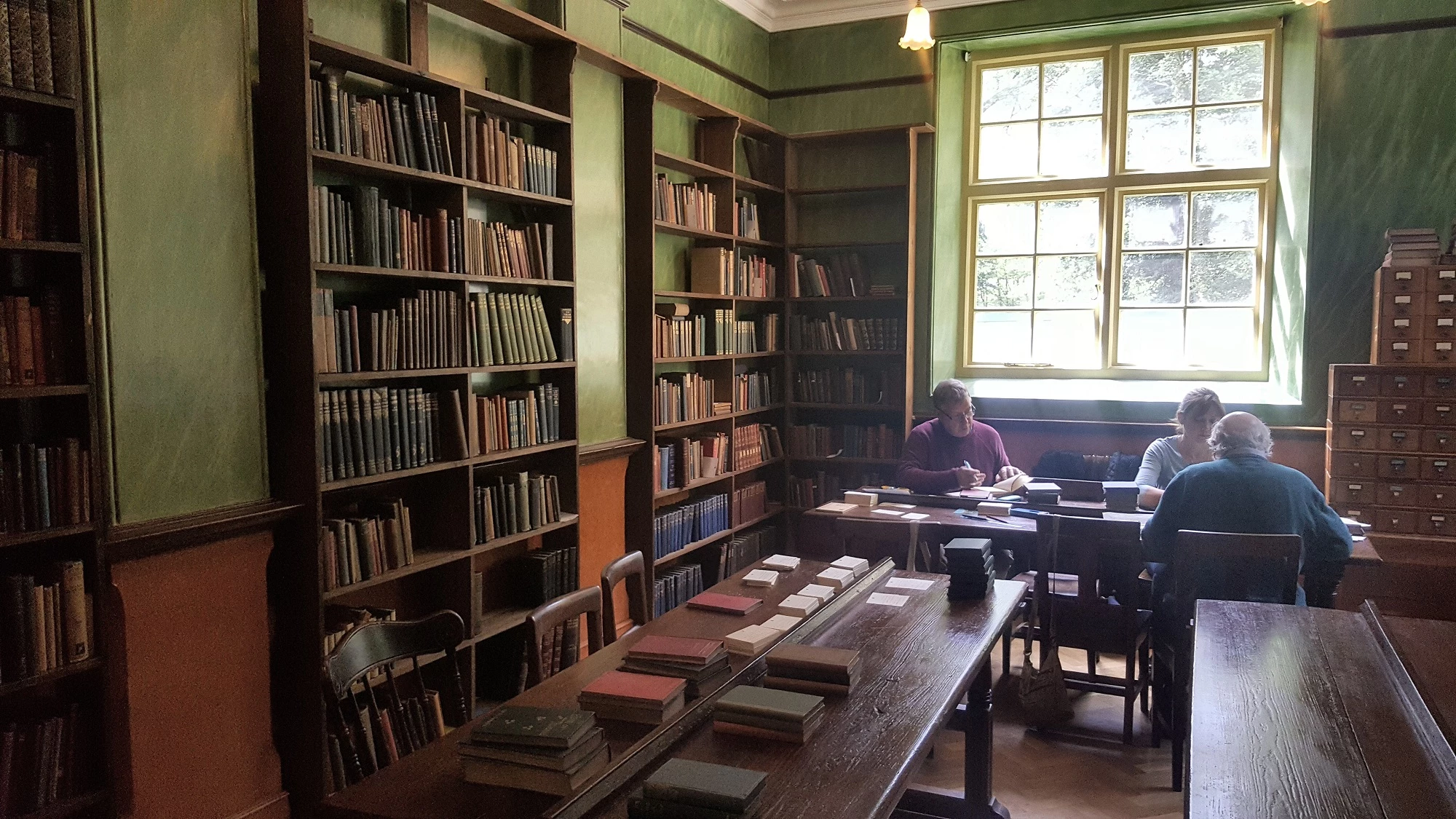

The Library of the Cardiff Naturalists' Society

, 9 October 2017

This year the Cardiff Naturalists’ Society is celebrating its 150th anniversary. You can read about the history of the Society, and its close links with the National Museum here and here.

Right from the outset the Society amassed its own Library focusing on natural history, geology, the physical sciences, and archaeology.

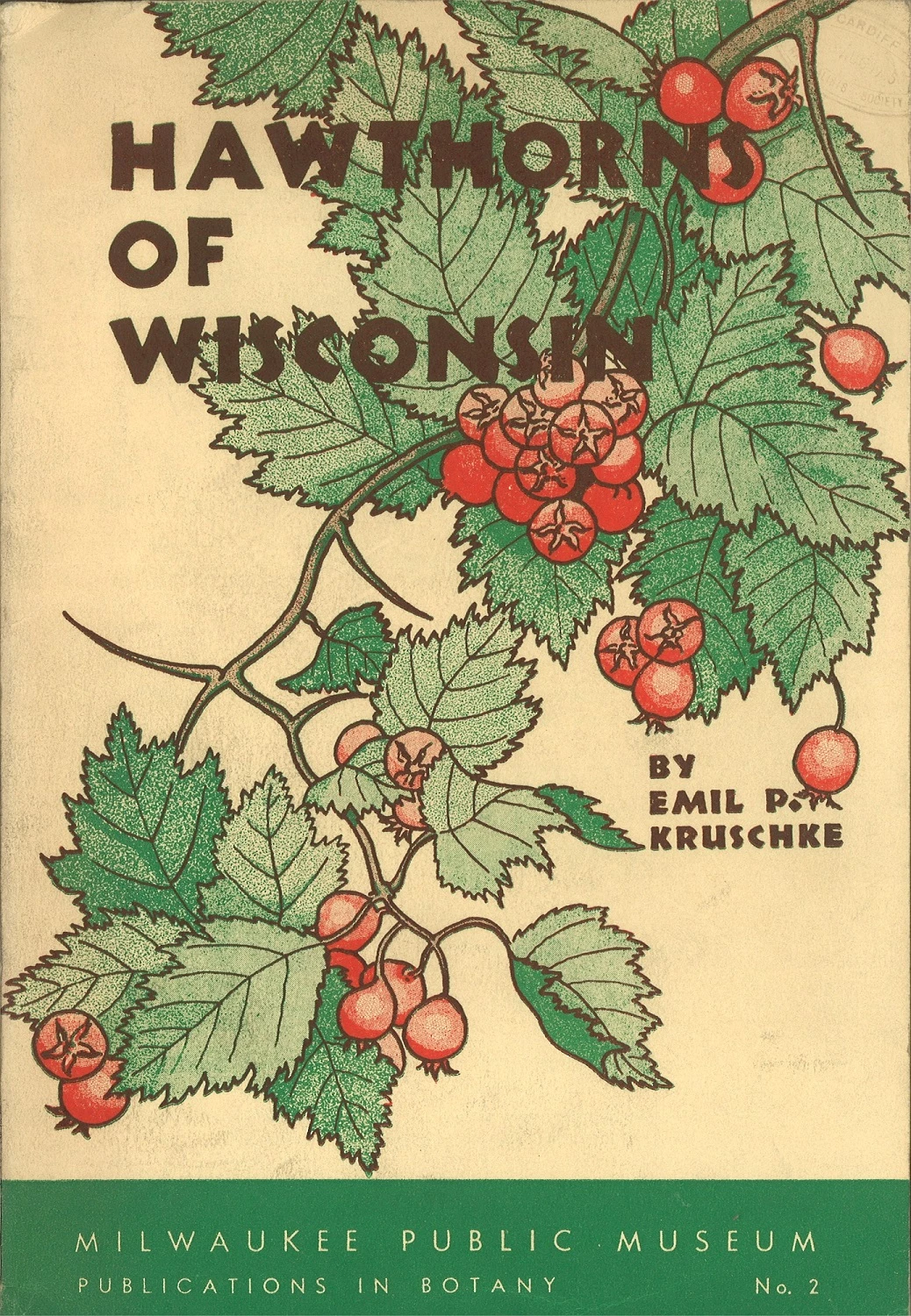

Many of the publications in the Library were received as exchanges with societies and institutions around the world. They would send out copies of their Transactions, and then receive copies of those organisations’ publications in return. Some of the institutions and societies they were exchanging with included; the Edinburgh Botanical Society; the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences; the South West Africa Scientific Society; the Polish Academy of Science; the Royal Society of Tasmania; the Sociedad Geographia de Lima; and the Kagoshima University in Japan.

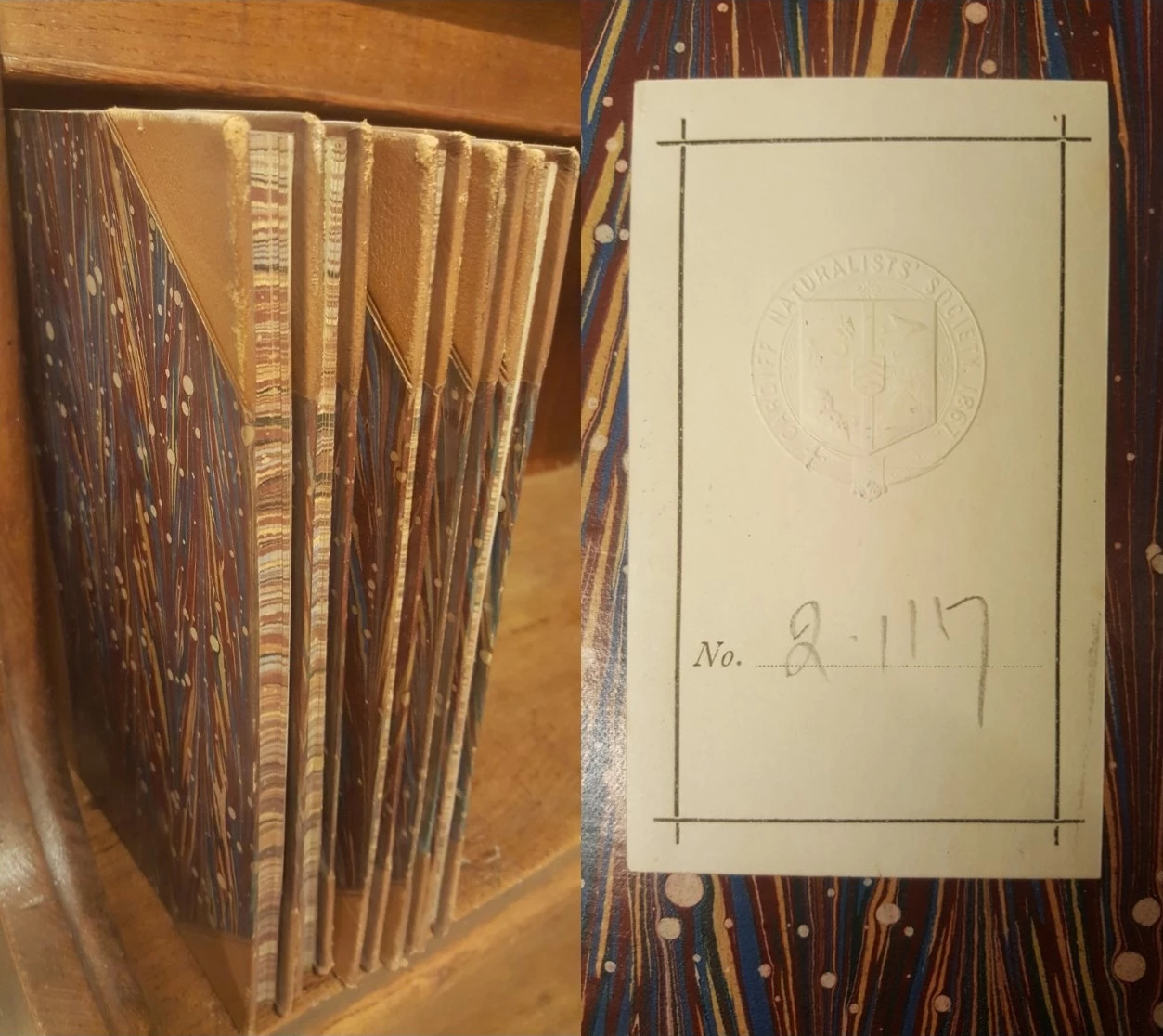

A number of the publications in the Library were later bound by William Lewis, a bookseller and stationer based in Duke Street in Cardiff. They all have beautiful marbled covers, endpapers, and a matching marbling pattern on the edges of the text block. Each one also has a bookplate with an embossed image of the Society logo, they are incredibly beautiful examples of bookbinding.

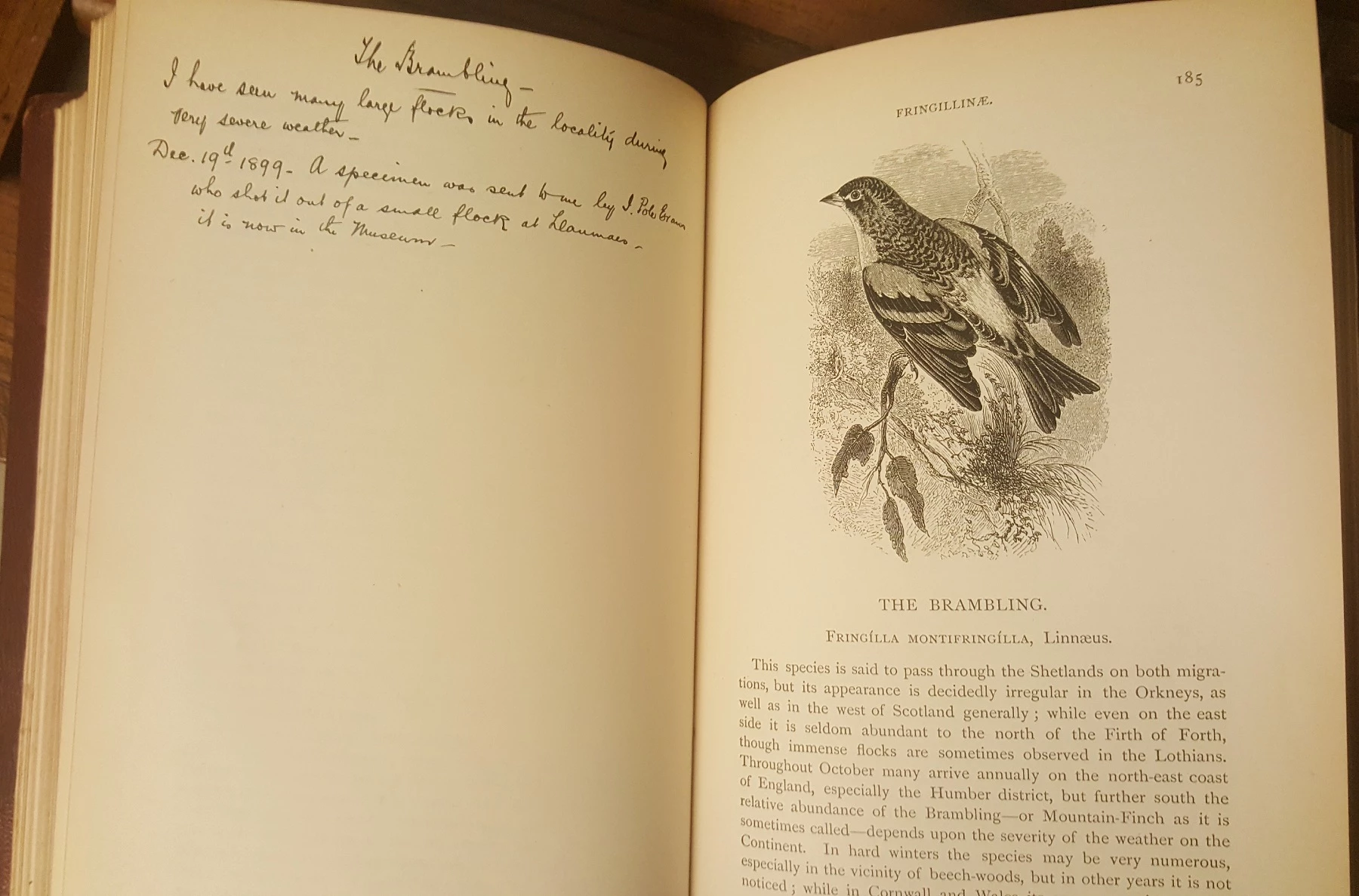

Not all the items in the Library were received on exchange, a great many were also the result of donations, especially by members. A lovely example is a copy of a second edition of An illustrated manual of British birds by Howard Saunders from 1899. Many of the pages contain annotations relating to whether the previous owner had encountered that particular species in the local area, such as spotting the nest of a pair of mistle-thrushes in Penylan in 1900. Unfortunately the signature of ownership is somewhat illegible, so it’s not possible to make out their name, all that we can tell is that they lived in Richmond Road in 1900.

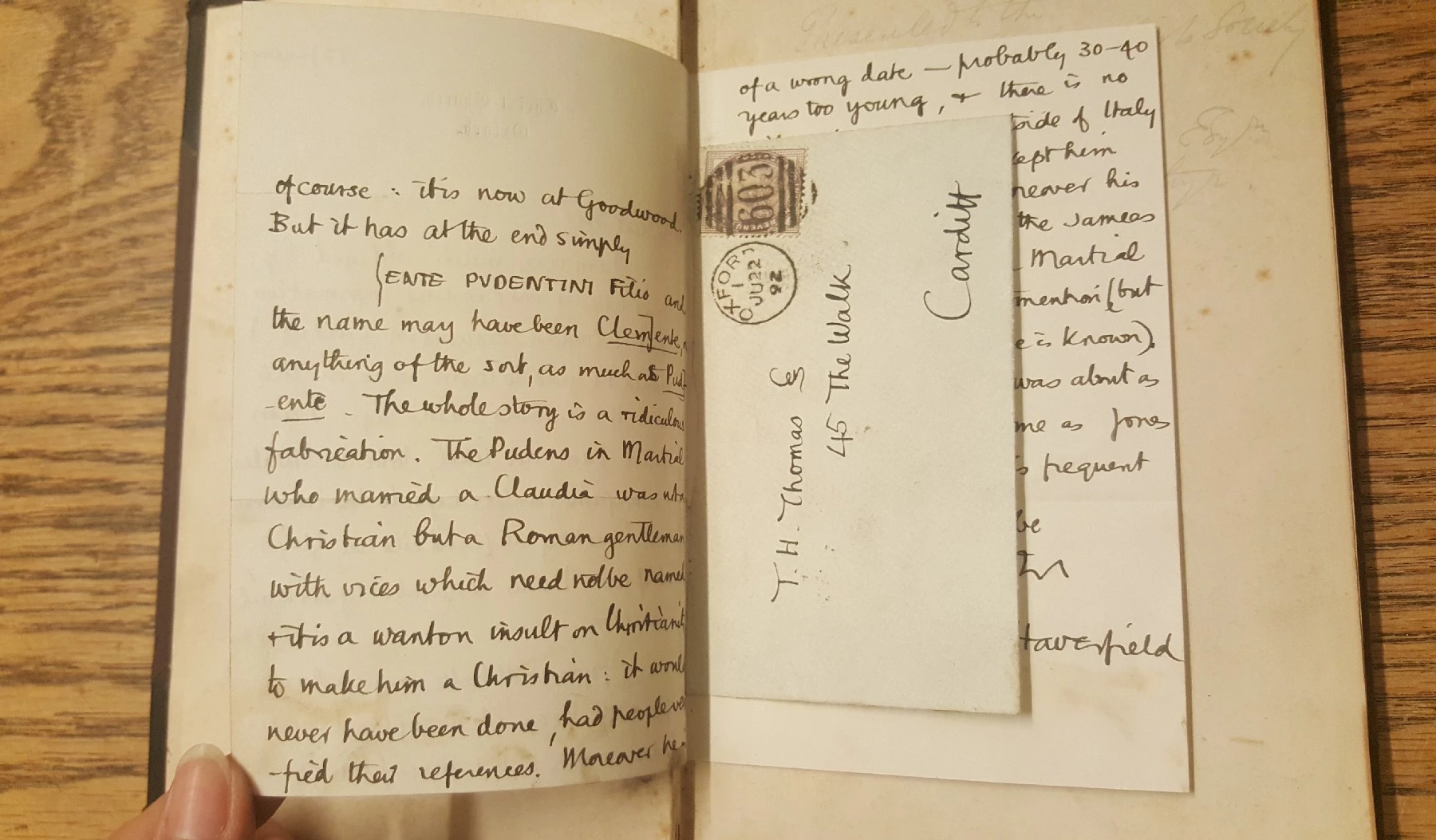

There is also a copy of Claudia and Pudens, a book by John Williams published in 1848. The book was presented to the Society by C. H. James Esq. of Merthyr, and in it is attached a letter to T. H. Thomas (a prominent member of the Society) dated 1892. The letter discusses Roman remains in Cardiff, and advises Thomas not to get drawn in to the ‘Claudia myth’, a popular theory suggesting a Claudia mentioned in the New Testament was a British princess. The author of the letter is quite scathing about the claims, calling them “a ridiculous fabrication”.

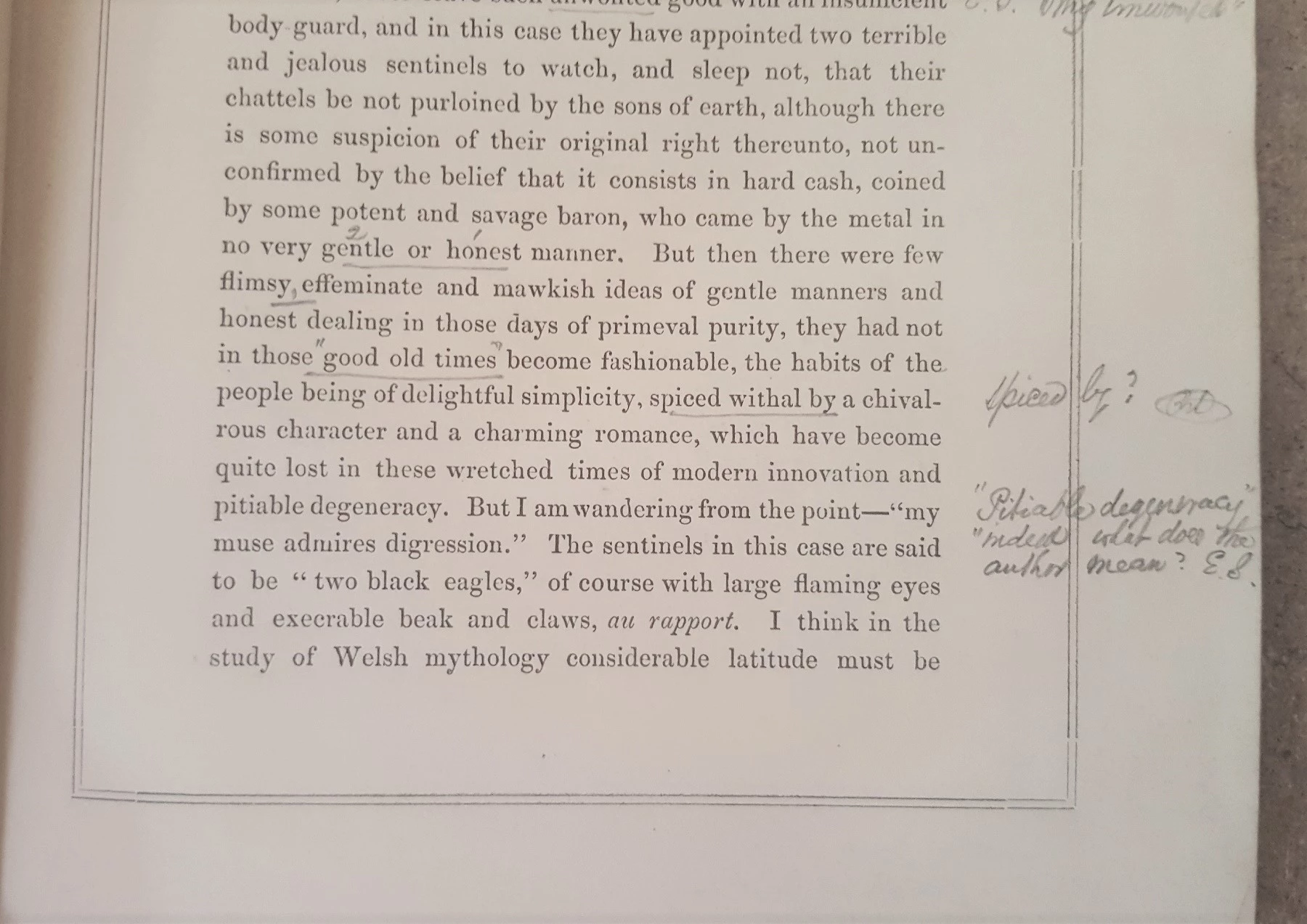

In 1996 a copy of Castell Coch by Robert Drane, a founding member of the Society was donated to the Library. It was published in 1857, and is now quite rare, as according to John Ward (former curator at the Cardiff Museum, and the National Museum), Drane subsequently destroyed as many copies of this book as possible! The copy donated to the Society contains annotations throughout, correcting or commenting on the contents, and a listing of all the people the author presented with copies.

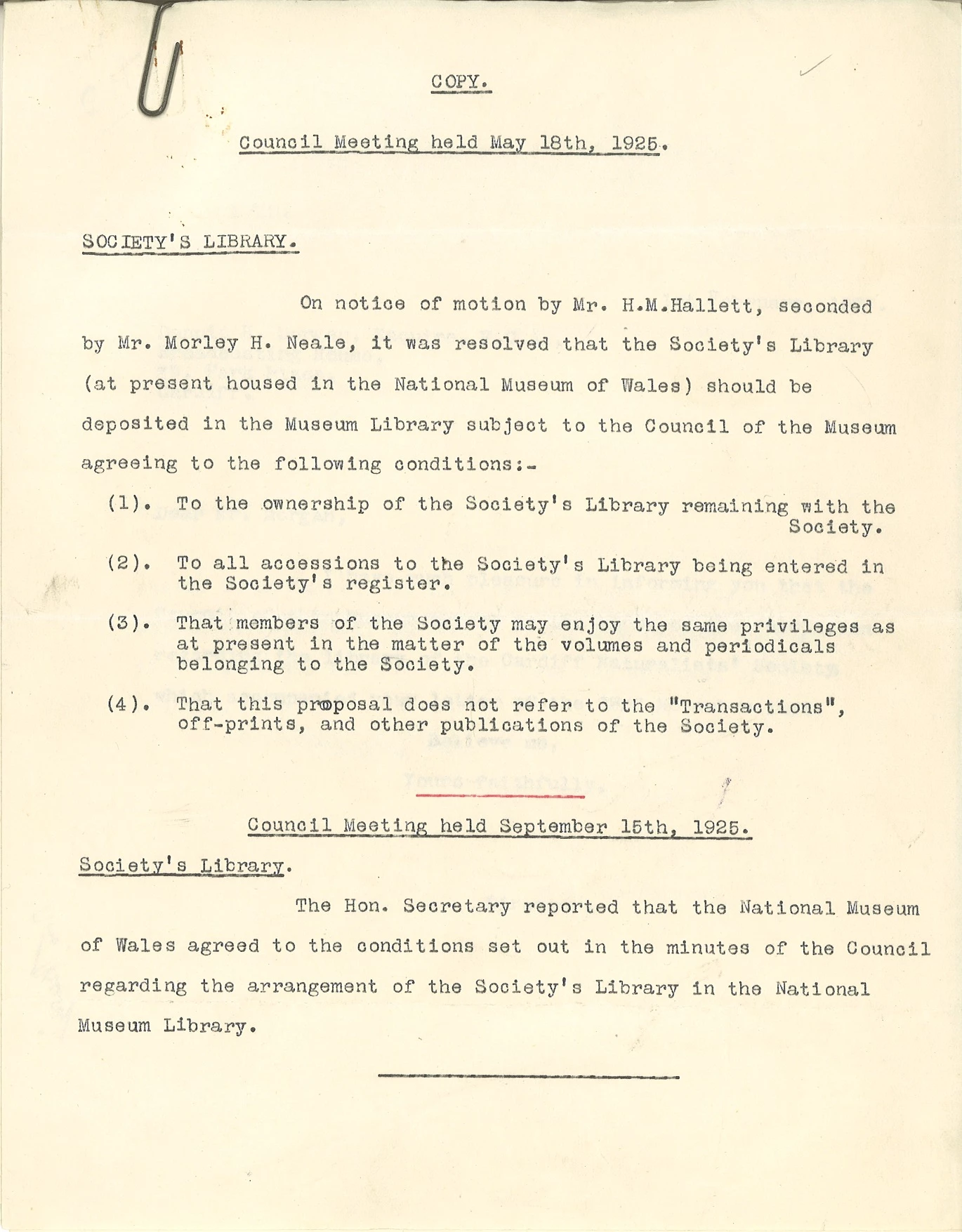

In 1925 the Society decided to place its Library in the Museum Library, with the following stipulations;

• To the ownership of the Society’s Library remaining with the Society

• To all accessions to the Society’s Library being entered in the Society’s register

• To all accessions to the Society’s Library being stamped with the Society’s stamp

• That members of the Society may enjoy the same privileges as at present in the matter of the volumes and periodicals belonging to the Society

• That this proposal does not refer to the “Transactions”, offprints, and other publications of the Society

Later in 1927 they decided to make it a permanent deposit, provided the Museum agreed to the additional stipulations;

● That members of the Society may enjoy the same privileges as at present in the matter of the volumes and periodicals belonging to the Society, and which may be received in the future in exchange for publications of the Society

● The Museum will bear the cost of all binding, which shall be undertaken as and when, in the opinion of the Museum Council finances permit. There shall be no differentiation, in this respect, between the Museum Library and the Society’s Library.

Although the Society’s Library had been in the care of the Museum Librarian since that time, the Honorary Librarian had always been a member of the Society. But, from 1964 the Honorary Librarian was both a member of the Society and a member of staff in the Museum Library.

List of Honorary Librarians

R.W. Atkinson 1892-1902

P. Rhys Griffiths 1902-1906

E.T.B. Reece 1907-1911

H.M. Hallett 1911-1948

H.N. Savory 1949-1962

G.T. Jefferson 1962-1964

E.H. Edwards 1964-1970

E.C. Bridgeman 1970-1976

W.J. Jones 1976-1985

J.R. Kenyon 1985-2013