A Window into the Industry Collections - April 2016

, 27 April 2016

As usual in this monthly blog post I’d like to share with you some of the objects that have been recently added to the industry and transport collections.

The first object this month is this rugby shirt with a ‘Tower Colliery’ badge. It was worn in the 1992 British Coal Cup Final. The donor was working in Taff Merthyr Colliery at the time, and took part in the 1992 Final in which Tower Colliery won. At the end of the match he swapped his Taff Merthyr Colliery RFC shirt for this Tower Colliery one.

"Hot Mill's"

Also, this month the museum was donated two paintings of Pontardawe Steel, Tinplate & Sheet Works. These were painted in 1955 by local amateur artist David Humphreys (born 1882), who had been employed in the works.

“Bar Mill” depicts the roughing stand of the steelworks bar mill, whilst “Hot Mill’s” depicts part of the sheet mills. In both paintings the artist has carefully recorded the working positions of the rollermen and the tools and features of the mill environments, such as the racked bar-turning tongs and cabin on the left of “Bar Mill”, and the tea cans (‘sten’) and jackets in the right foreground of “Hot Mill's”. Such attention to detail to the plant and environment is a distinctive hallmark of an industry ‘insider’ recording scenes he was intimately familiar with.

This electric cap lamp was manufactured by Oldham & Son Ltd. in about 1995. It is a standard coal-mining specification cap lamp, but is distinguished by being specifically inscribed “H.M.I” (Her Majesty’s Inspector (of Mines)) on the metal battery lid. It was owned and used by one of the South Wales Inspectors of Mines between 1996 and c.2004 during the course of his work.

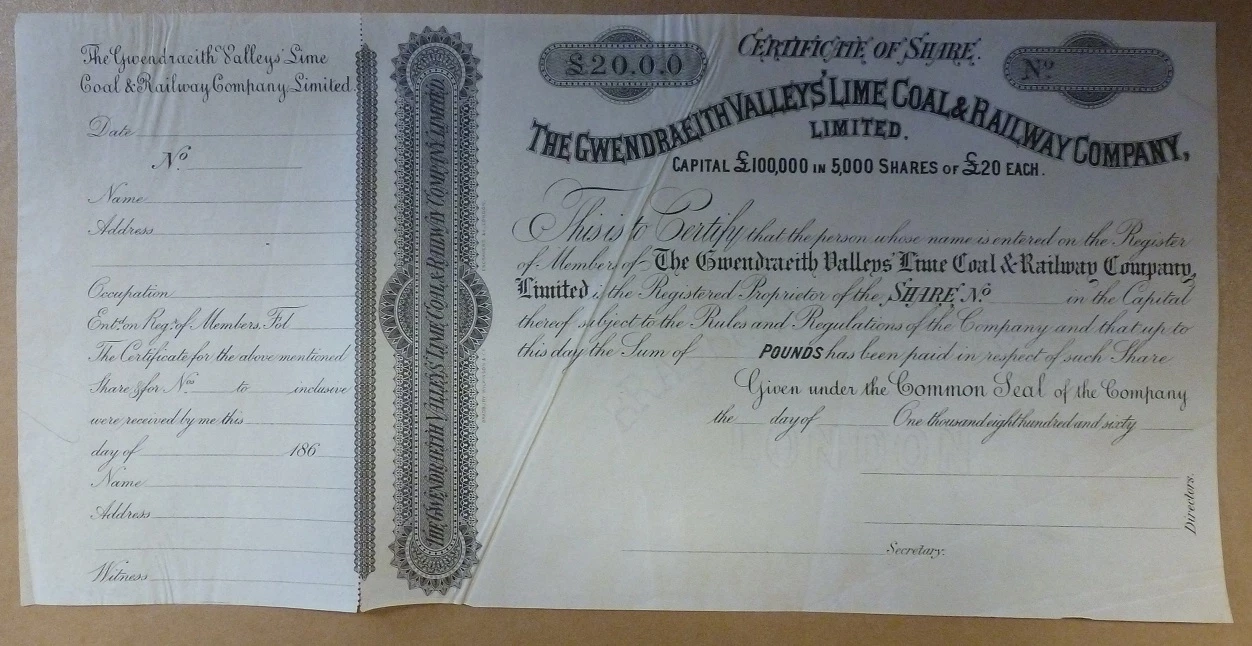

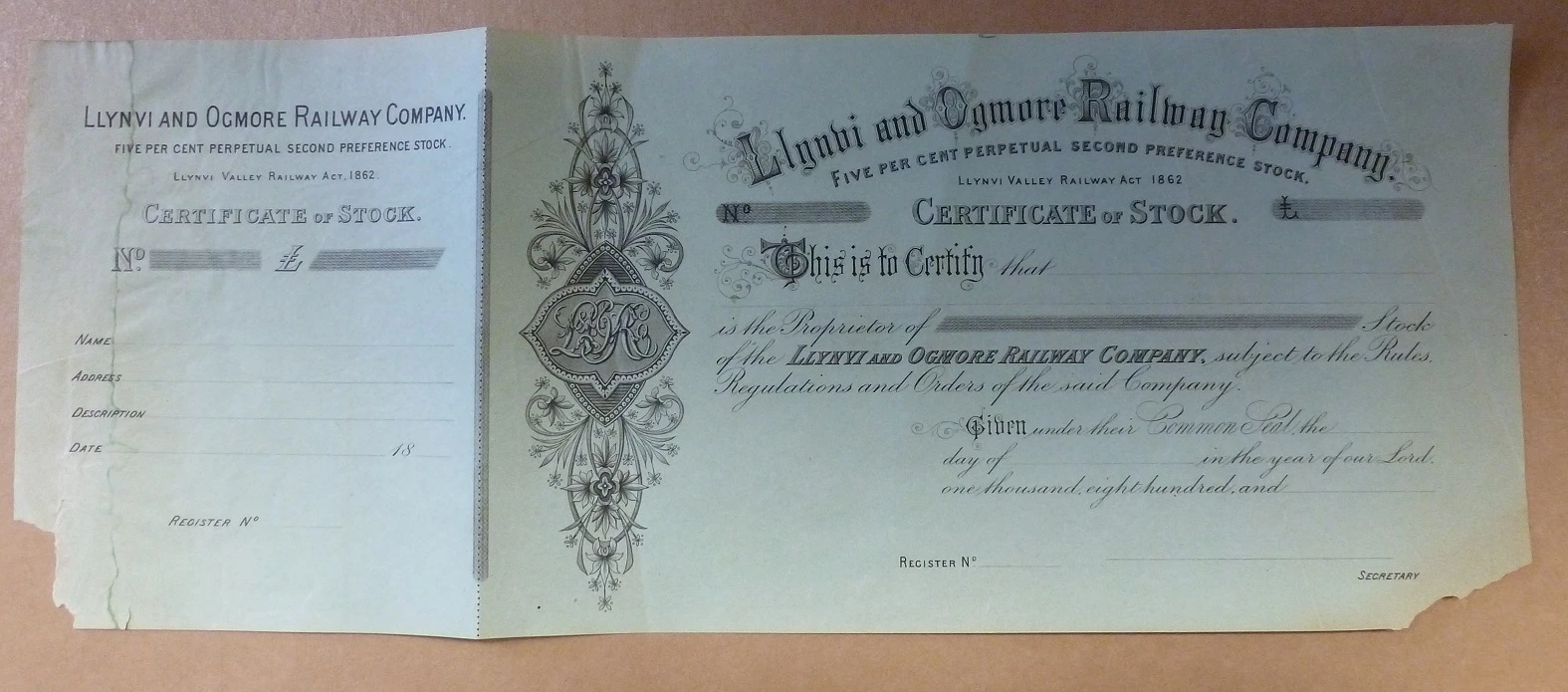

Amgueddfa Cymru holds by far the largest and wide-ranging Welsh-interest share certificate collection held by any public museum. The collection ranges across railway and maritime transport, coal mining, the mining and smelting of metals, general industry, and service industries (finance, leisure, consumer products, etc.).

The museum is actively collecting in this field, and this month we have added two further examples to the collections.

The first is for the The Gwendraeith [sic] Valleys Lime Coal & Railway Co Ltd. This company was formed in February 1868 to develop the limestone and coal deposits in the lower Gwendraeth Valley. The company wanted to develop limestone quarrying and lime burning, and to acquire the existing railway which it intended to extend into the coalfield on the south side of the valley. However only 185 shares were subscribed to and with insufficient capital the company was wound up in December 1869, having achieved nothing on the ground. This certificate is a good example of a number of companies that tried unsuccessfully to develop the anthracite area of the south Wales coalfield.

The second certificate is for the Llynvi & Ogmore Railway Company. This company was formed in 1866 to amalgamate the broad gauge Llynvi Railway Company of 1846 and the standard gauge Ogmore Valley Railway of 1863. Both companies’ railways were focussed on Porthcawl Harbour and both were dominated by the Brogden family, Lancashire industrialists who developed the Maesteg iron and coal industry and who expanded dock facilities at Porthcawl. The company was managed by the Great Western Railway from 1873, and eventually absorbed by the G.W.R. in 1883.

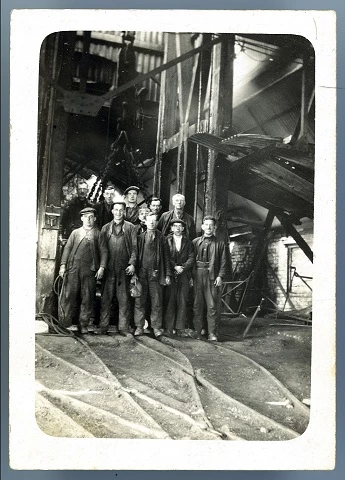

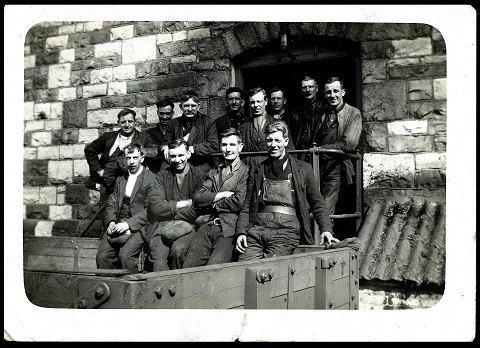

This object is a cast iron artillery round made in Blaenavon steelworks in the mid 19th century. Surplus ones were re-forged for bridle chains on colliery headgears. The chains can be seen in the last photograph of the three below showing blacksmiths at Big Pit in about 1950.

Artillery round made in Blaenavon steelworks.

Mark Etheridge

Curator: Industry & Transport

Follow us on Twitter - @IndustryACNMW