11th December 2015 at the National Museum Cardiff from 10.30am to 3.30pm.

Join us for the Christmas version of this one day conference organized by Amgueddfa Cymru: National Museum Wales, The Federation of Museums and Art Galleries of Wales and Cardiff University. The theme is ‘Conservators in action’ and will highlight some of the great work done by conservators across Wales.

A good mix of talks is being arranged;

- Gemma McBader, this years winner of the Pilgrim Trust Student Conservator of the Year Award, will talk about her project 'Significance-led conservation of a 19th century Ethiopian shield'.

- Helen Baguley on her experiences as a music internship at St Fagans National History Museum.

- Adam Webster will be exploring the conservation of the Stradling family memorial panels.

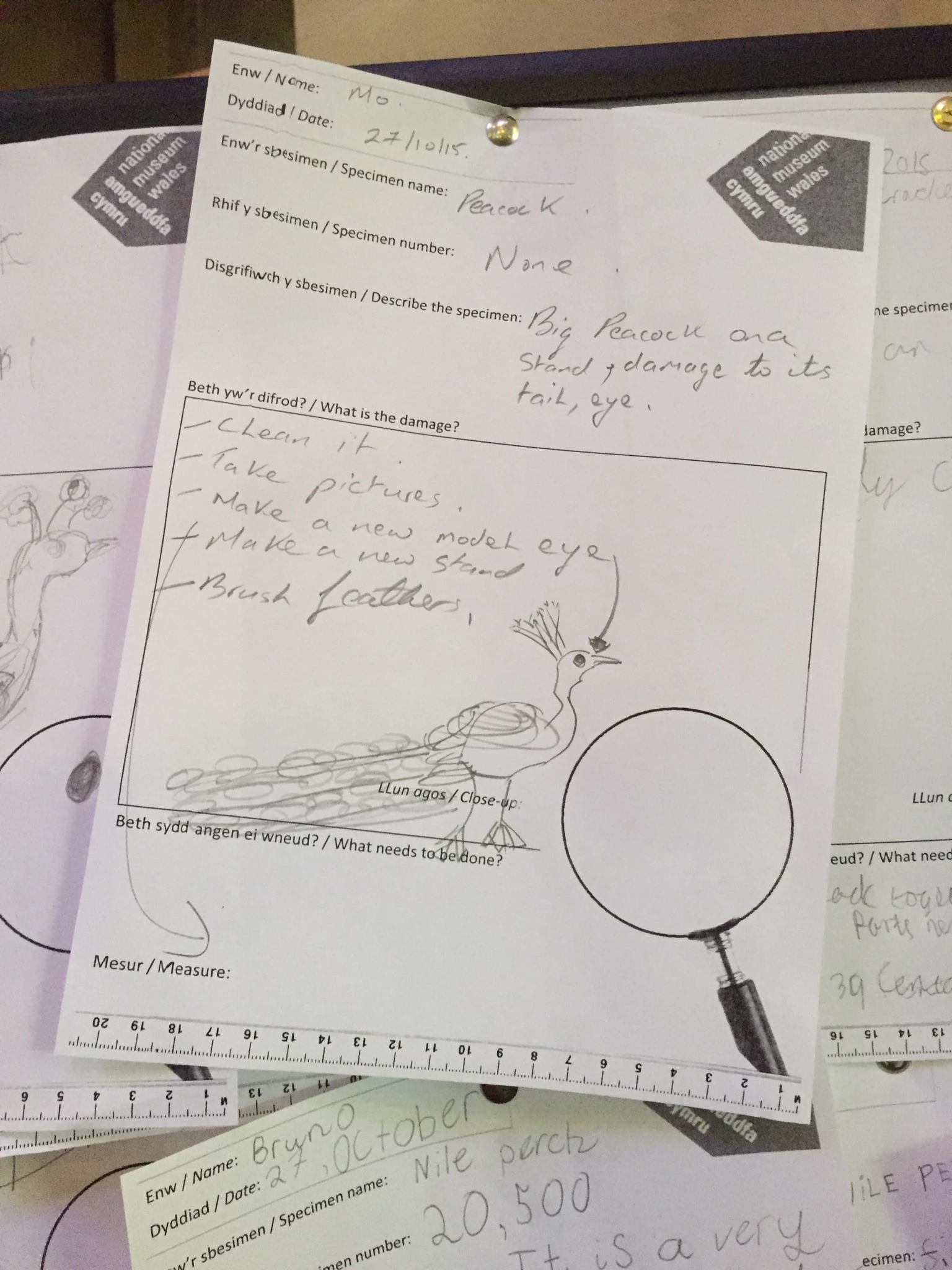

- Ruth Murgatroyd on preparing the specimens for the ‘Stuffed, pickled, pinned’ exhibition for their 3 year tour.

- Julie McBain will be challenging authenticity in textile conservation.

- Jane Rutherfoord discusses the uncovering, conservation and significance of the 15th century wall paintings at Llancarfan.

- Caroline Buttler will be looking at the challenges of conserving, moving and displaying a few tons of fossil tree root!

- Katie Mortimer Jones will be providing an insight into the way the Natural sciences at AC-NMW integrate the use of social media.

A draft program for the day is;

10:00 Tea/Coffee

10:30 Intro

10:40 Katie Mortimer (AC-NMW). Using social media to highlight and promote the work of the natural sciences at Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales.

11:05 Helen Baguley (Cardiff University). Being an ICON intern: a note on musical instrument conservation.

11:30 Caroline Buttler (AC-NMW). Conservation of the Brymbo Fossil forest.

11:55 BREAK

12:10 Gemma McBader (University College London). Significance-led conservation of a 19th century Ethiopian shield.

12:35 Adam Webster (AC-NMW). Adventures with Sir Harry Stradlinge and Colyn Dolyphn a Brytaine Pirate; the conservation and restoration of the Stradling Family memorial panels.

13:00 LUNCH

14:00 Ruth Murgatroyd (Cardiff University) - Packed, padded & pinned: preparing natural science specimens for a three year tour.

14:25 Julia McBain (Cardiff University). Conserving what is real, the challenge of authenticity in textile conservation.

14:50 Jane Rutherfoord (Rutherfoord Conservation Limited). Uncovering, conservation and significance of the 15th century wall paintings at Llancarfan.

15:20 Discussion

15:40 Short tours are possible, before retiring to the pub!

If you have any queries about the program please contact julian.carter@museumwales.ac.uk. We will be looking to finish by around 3.30pm, with the additional option of some short collection tours afterwards if you wish to stay longer. For those requiring some further refreshment the tours will be followed by a seasonal visit to a local pub.

The cost of the day is £20 which includes lunch (£10 for students). If you wish to join us, please email your booking information before 7 December 2015 and follow it with a cheque or Purchase Order payable to Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales to

Katrina Deering

National Collections Centre

Heol Crochendy

Parc Nantgarw CF15 7QT

Please E-mail any booking queries to katrina.deering@museumwales.ac.uk

Booking information

Name:

Organisation:

E-mail address:

Payment enclosed or to follow: Yes/No

Students are permitted to pay cash on the day, but must book a place by 7 December 2015. Places are allocated on a first come first served basis.

Please include any dietry requirements with your booking information.

Conservation Matters in Wales conferences are held twice a year in Wales, UK and bring together examples of best practice, case studies and research in conservation and collections care, and provide networking opportunities for conservators and museum, library and archive professionals.